Childhood in Pittsburgh

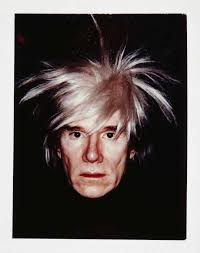

Andy Warhol, born on August 6, 1928, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, emerged from humble beginnings rooted in his Rusyn immigrant heritage. His parents, Ondrej and Julia Warhola, immigrated from Mikó, Austria-Hungary, instilling values of hard work and community that profoundly shaped Warhol’s identity. The Warhola family lived in various neighborhoods throughout Pittsburgh, including 55 Beelen Street and 3252 Dawson Street in the Oakland area. Their devout Ruthenian Catholic faith was a cornerstone of family life, with regular attendance at St. John Chrysostom Byzantine Catholic Church fostering a sense of belonging and tradition.

As the fourth child in a family of four—following two older brothers, Paul and John, and a sister who tragically died in infancy—Warhol’s early years were marked by familial love and the challenges of modest means. The struggles of an immigrant family instilled in him a unique perspective that later permeated his artwork. From a young age, Warhol demonstrated remarkable artistic talent, a gift that did not go unnoticed by his mother. Her encouragement laid the groundwork for his future pursuits, allowing his creativity to flourish against Pittsburgh’s industrial backdrop.

Warhol’s childhood was enriched by the cultural influences surrounding him. The vibrant community of Pittsburgh, blending immigrant traditions with American values, provided fertile ground for his imagination. His early experiences, from drawing in school notebooks to exploring the city’s artistic heritage, ignited a passion for creativity that would propel him into the world of art.

As he navigated his formative years, the seeds of Warhol’s artistic identity were sown. The supportive environment of his childhood encouraged him to embrace his talents, setting the stage for a career that would eventually redefine the boundaries of art. The combination of his immigrant background, familial support, and Pittsburgh’s cultural milieu shaped not only his artistic vision but also his understanding of the interplay between art and society—themes that would resonate throughout his life and work.

Education and Artistic Beginnings

Andy Warhol’s artistic journey began to take shape during his formative years in Pittsburgh, a city that inspired his creative vision. After graduating from Schenley High School in 1945, where he received a Scholastic Art and Writing Award, Warhol embarked on a path leading to the heart of the American art scene. His early education laid a solid foundation, igniting a passion for art that would flourish in the years to come.

Warhol enrolled at the Carnegie Institute of Technology, now known as Carnegie Mellon University, to study commercial art. This decision proved pivotal, as the institution provided him with the tools and environment to explore his artistic inclinations. During college, he became actively involved in the campus Modern Dance Club and the Beaux Arts Society, experiences that broadened his artistic exposure. Here, Warhol began to blend his commercial sensibilities with a burgeoning artistic identity, a duality that would define much of his later work.

As art director for the student magazine Cano, Warhol showcased his emerging talent. His first published works in 1948 and 1949 marked the start of his professional journey in visual communication. Earning his Bachelor of Fine Arts in pictorial design in 1949 equipped him with the skills necessary for a career in the arts.

Upon graduating, Warhol made the bold decision to move to New York City, a vibrant metropolis brimming with artistic potential. This transition was not merely geographical; it was an opportunity to immerse himself in a world that promised both challenges and rewards. His first solo show at the Hugo Gallery in 1952, though met with lukewarm reception, was a crucial step in his artistic evolution, marking his entry into the art community where he would soon make an indelible mark.

By 1956, Warhol’s increasing visibility was underscored by his inclusion in a group exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. This recognition signaled the beginning of his ascent within the art world. During this formative period, Warhol began to experiment with his unique style, characterized by the innovative blending of commercial techniques with fine art. His background as a commercial illustrator, combined with his academic training, set the stage for the iconic silkscreen methods that would later define his most celebrated works.

Warhol’s early experiences in Pittsburgh and his subsequent education were more than mere stepping stones; they were the crucible in which his artistic identity was forged. The nurturing environment provided by his family, coupled with rigorous academic training, instilled in him a sense of purpose and a relentless drive to explore the boundaries of art. As he transitioned into the pulsating world of New York’s art scene, he carried with him the rich tapestry of his early life, ready to transform everyday imagery into profound commentary on culture, consumerism, and the nature of fame.

Transition to New York

In 1949, armed with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from the Carnegie Institute of Technology, Andy Warhol embarked on a transformative journey to New York City, a vibrant metropolis brimming with artistic energy and innovation. This move marked the beginning of a new chapter that would ultimately redefine the boundaries of art and culture in America.

Upon his arrival, Warhol quickly immersed himself in the dynamic art scene, eager to make his mark. His first solo exhibition at the Hugo Gallery in 1952, though met with a lukewarm reception, was significant. It signaled his entry into the complex world of New York art, where ambition and creativity collided. Despite the lack of immediate acclaim, Warhol’s determination never wavered; he understood that success in the art world often required navigating rejection and criticism.

By 1956, Warhol’s efforts began to bear fruit as he was included in his first group exhibition at the prestigious Museum of Modern Art. This recognition marked a turning point, solidifying his presence within the artistic community. During these formative years, Warhol was not merely an observer but an active participant in the evolving dialogue of modern art. He began to develop a unique style that blurred the lines between commercial illustration and fine art, a characteristic that would become synonymous with his later works.

Warhol’s early career as a commercial illustrator played an instrumental role in shaping his artistic voice. His work for magazines, including drawing shoes for Glamour, was more than a job; it was a training ground where he honed his skills in visual communication and learned to navigate the complexities of consumer culture. This foundation would later inform his iconic silkscreen techniques, allowing him to elevate everyday objects into high art.

During this period in New York, Warhol was not only focused on his artistic endeavors but also acutely aware of the cultural landscape surrounding him. The city was a melting pot of ideas, and Warhol was drawn to the eclectic mix of personalities, styles, and movements that defined the 1950s and 60s. His experiences in this bustling environment fueled his creativity, leading him to experiment with various mediums and techniques that would ultimately set him apart from his contemporaries.

As the 1960s approached, Warhol’s artistic vision began to crystallize. His early years in New York were marked by a relentless pursuit of innovation and a desire to carve out a distinct identity in a city that thrived on reinvention. This journey was not only about finding his place as an artist but also about understanding the interplay between art, advertising, and the burgeoning celebrity culture that would come to dominate his work.

In retrospect, Warhol’s transition to New York was not merely a geographic relocation; it was a crucible of creativity that forged him into a cultural icon. The experiences he gathered, the challenges he faced, and the inspirations he encountered during these formative years laid the groundwork for a career that would resonate through the decades, influencing generations of artists and shaping the very fabric of contemporary art.

The Factory and Pop Culture

In the vibrant tapestry of 1960s New York City, The Factory emerged as a beacon of creativity and counterculture. More than just a studio, it became a cultural epicenter and a sanctuary for the avant-garde, where the boundaries of art, celebrity, and social commentary blurred into a dazzling kaleidoscope. Andy Warhol’s Factory attracted a diverse mix of artists, intellectuals, drag queens, and Hollywood celebrities, all drawn to Warhol’s vision and charisma.

The Factory buzzed with laughter, debate, and the sounds of creative experimentation. Here, Warhol transformed conventional notions of art, inviting myriad personalities to contribute to his artistic output. The artists and performers who frequented this space played a pivotal role in shaping Warhol’s work, influencing not only his visual art but also his groundbreaking films. The atmosphere was electric, charged with a sense of possibility and rebellion against the status quo.

Among the notable figures at The Factory were Edie Sedgwick, a striking muse embodying the spirit of the era, and Nico, the hauntingly beautiful singer of the Velvet Underground. These “Warhol superstars” became integral to his creative process, their lives and personas interwoven with his art. Warhol’s ability to capture their essence on canvas and film created a unique dialogue between art and life, inviting viewers into a world that was as glamorous as it was gritty.

Warhol’s innovative approach to media was evident in his films, which often featured long takes and minimal action, challenging traditional cinematic narratives. Works like “Chelsea Girls” showcased the eclectic personalities inhabiting The Factory, blurring the lines between performance and reality. This radical departure from conventional filmmaking not only redefined the art form but also solidified Warhol’s status as a leading figure in the pop art movement.

The Factory’s influence extended beyond art; it became a symbol of the cultural revolution of the 1960s. During a time when society grappled with issues of identity, consumerism, and the nature of fame, Warhol’s studio served as a crucible for ideas that resonated throughout the decade. Here, he embraced the notion of art as a reflection of contemporary culture, using everyday objects and celebrity images to comment on the shifting values of American society.

Warhol’s genius lay in his ability to synthesize diverse influences, creating a body of work that was both provocative and accessible. The Factory nurtured creativity and challenged definitions of art and culture, establishing Warhol as a defining voice of his generation. As the 1960s unfolded, The Factory continued to shape the landscape of pop culture, leaving an indelible mark on the art world and beyond.

Iconic Works

In the 1960s art scene, few threads shine as brightly as those woven by Andy Warhol. His masterpieces, particularly “Campbell’s Soup Cans” and “Marilyn Diptych,” defined the pop art movement and encapsulated the era’s complex relationship with consumer culture and celebrity.

“Campbell’s Soup Cans,” unveiled in 1962, marked a watershed moment in Warhol’s career and the art world. This series of 32 canvases, each depicting a different flavor of Campbell’s soup, was Warhol’s first major exhibition and revolutionary. The use of silkscreen printing allowed for the repetition of images, mirroring the mass production methods of consumer goods and advertising. Warhol’s choice of subject matter—a staple of American households—transformed the mundane into the extraordinary, inviting viewers to reconsider the significance of everyday objects. Warhol famously quipped that he had Campbell’s soup for lunch most of his life, suggesting an intimate connection between his personal experiences and the commercial art he created. This blend of autobiography and consumerism became a hallmark of his work.

Following closely, the “Marilyn Diptych” emerged in the same year, further solidifying Warhol’s status as a pop art icon. The diptych features a striking display of Marilyn Monroe’s visage, rendered in bold colors and repeated in a grid-like pattern. This work sparked discussions about celebrity culture and the nature of fame itself. The vibrant hues juxtaposed with the haunting repetition of Monroe’s image evoke both allure and melancholy, reflecting the fleeting nature of stardom. Warhol’s portrayal of Monroe became a commentary on the commodification of celebrities, questioning whether the public’s obsession with fame could overshadow the individual behind the persona.

Both “Campbell’s Soup Cans” and “Marilyn Diptych” generated considerable controversy, prompting debates that questioned the essence of art. Critics argued that Warhol’s embrace of commercial products as artistic subjects undermined the integrity of artistic endeavor. Yet, this blurring of boundaries between art and commerce was intentional, challenging traditional notions of artistic expression. Warhol provocatively stated that Coca-Cola was a symbol of equality, accessible to everyone, regardless of wealth. Through his art, Warhol held up a mirror to society, reflecting its obsession with consumer goods, fame, and the superficial aspects of modern life.

In the kaleidoscopic world of the 1960s, Warhol’s iconic works emerged not just as art but as cultural commentary, encapsulating the zeitgeist of an era that was both enamored with and critical of its consumerist tendencies. His ability to provoke thought and ignite conversation secured his place as a leading figure in the pop art movement, forever altering the landscape of contemporary art.

The Critique of Consumerism

Andy Warhol’s relationship with consumer culture was a complex tapestry of admiration and critique, intricately woven into the fabric of his art. His work in the 1960s ignited fascination and intense debate, particularly among critics who questioned the integrity of his artistic vision. At a pivotal symposium at the Museum of Modern Art in December 1962, Warhol found himself at the center of controversy. Critics accused him of yielding to the very consumerism he portrayed, arguing that by elevating commercial products to the status of art, he undermined the essence of artistic expression.

Warhol’s iconic series, “Campbell’s Soup Cans,” exemplifies this tension. This series featured 32 canvases, each depicting a different flavor of Campbell’s soup, marking Warhol’s first major exhibition. It was not merely a celebration of consumer goods; it was a profound commentary on the commodification of everyday objects. Warhol employed silkscreen techniques, allowing for repetition that mirrored mass production and advertising, effectively transforming a mundane product into a cultural icon. In a playful yet poignant twist, he remarked that he had Campbell’s soup for lunch most of his life, underscoring the intersection of personal experience and commercial art.

The “Marilyn Diptych,” created in the same year, further solidified Warhol’s status as a pop artist and underscored his fascination with celebrity culture. The vibrant colors and repeated images of Marilyn Monroe sparked discussions about fame and its fleeting quality. Here, Warhol captured the essence of a cultural moment, reflecting society’s obsession with celebrity and the superficial aspects of modern life. The diptych’s duality—one side bursting with color and life, the other fading to monochrome—mirrored the duality of fame itself, where glamour and despair coexist.

Warhol’s embrace of consumerism was not without its critics. Many contemporaries viewed his work as a betrayal of artistic integrity, arguing that by using commercial products as subjects, he blurred the lines between art and commerce. Yet, Warhol’s intention was to challenge these boundaries. His assertion that Coca-Cola represented equality—accessible to everyone regardless of wealth—encapsulated his multifaceted relationship with consumer culture. In his world, art was not a sanctuary removed from daily life; it was a mirror reflecting society’s obsessions, desires, and contradictions.

Through his work, Warhol positioned himself at the forefront of cultural commentary during the 1960s. He invited audiences to confront the realities of a consumer-driven society, compelling them to question their relationships with fame, goods, and the very nature of art itself. In doing so, he redefined the role of the artist and left an indelible mark on contemporary culture, prompting ongoing debates about the intersections of art, commerce, and identity that resonate to this day.

Defining the Superstars

In the vibrant tapestry of 1960s New York, a unique circle of bohemian and counterculture figures emerged, forever intertwined with Andy Warhol’s legacy. These individuals, whom Warhol affectionately dubbed the “superstars,” were not merely muses; they embodied an era celebrating artistic rebellion and cultural experimentation. Notable personalities included Edie Sedgwick, the enigmatic blonde who captivated audiences with her striking beauty, and Nico, the hauntingly ethereal singer of the Velvet Underground, whose collaborations with Warhol blurred the lines between music and art.

The Factory, Warhol’s legendary studio, became a sanctuary for these eclectic talents—Joe Dallesandro, Viva, Ultra Violet, Holly Woodlawn, Jackie Curtis, and Candy Darling were all part of this vibrant collective. Each superstar contributed their unique flair, enriching the narrative and aesthetic of Warhol’s work. The Factory pulsated with creativity and innovation, where artistic boundaries were continually challenged.

Warhol’s superstars were not just participants in his films; they were co-creators, shaping the thematic depth of his art. Edie Sedgwick, with her bold style and captivating persona, became central to Warhol’s universe, starring in iconic films like “Poor Little Rich Girl” and “Ciao! Manhattan.” Her presence symbolized the allure of fame and the darker undercurrents of the celebrity lifestyle that Warhol often explored.

These superstars represented a blend of artistic talent and cultural rebellion, each navigating the complexities of identity and fame in their own way. Holly Woodlawn, known for her unapologetic authenticity, emerged as a symbol of the transgender experience at a time when such representation was scarce. Candy Darling, with her glamorous allure and tragic narrative, encapsulated the fleeting nature of fame that Warhol keenly observed.

Through these collaborations, Warhol captured the essence of his superstars while painting a broader picture of the cultural landscape of the 1960s. Their influence extended beyond the screen and canvas, shaping Warhol’s creative process and the fabric of contemporary art. The superstars were more than characters in Warhol’s narrative; they reflected a society grappling with the implications of fame, identity, and the commodification of the self.

In this kaleidoscopic world of art and celebrity, the Warhol superstars became icons in their own right, leaving an indelible mark on cultural consciousness. Their stories, intertwined with Warhol’s vision, remind us of the power of collaboration and the transformative nature of art, where the lines between creator and creation blur, giving rise to a new understanding of identity and expression.

Films and Performances

In the heart of 1960s New York City, Andy Warhol reshaped art and cinema with his groundbreaking underground films, prominently showcasing his eclectic group of “superstars.” This unique collective included figures such as Edie Sedgwick, Nico, Joe Dallesandro, Viva, Ultra Violet, Holly Woodlawn, Jackie Curtis, and Candy Darling. They not only starred in Warhol’s cinematic ventures but also embodied the avant-garde spirit that defined the era. The Factory emerged as a pulsating hub of creativity, where art, film, and performance converged, allowing these personalities to flourish.

Warhol’s films were revolutionary in their departure from conventional storytelling, often embracing a more experimental and provocative approach. One of his most notable works, “Chelsea Girls,” released in 1966, epitomized this style. The film boldly explored the lives of his superstars in a split-screen format that allowed multiple narratives to unfold simultaneously. This innovative technique challenged cinematic conventions and blurred the lines between art and entertainment, establishing Warhol’s superstars as cultural icons within the New York art scene.

The Factory was more than just a film studio; it was a dynamic space where creativity thrived. Events held there, such as the launch party for Nico’s album “The Marble Index,” showcased the intersection of music, film, and art. These gatherings were infused with the energy of artistic collaboration and the spirit of rebellion that characterized the counterculture movement. Warhol’s superstars became not only muses but also collaborators, each contributing their unique flair to the collective vision Warhol sought to create.

Warhol’s films often reflected the complexities of identity and the nature of fame. His superstars, with their diverse backgrounds and striking personas, became emblematic of the fleeting nature of celebrity. Through these performances, Warhol explored the notion that fame is both a gift and a burden, a theme that resonated deeply within the cultural zeitgeist of the time. The lives of the superstars served as a testament to this duality, as they navigated the liminal space between art and notoriety, often becoming larger-than-life figures in the public eye.

The impact of Warhol’s films extended far beyond the screen. They redefined the roles of artist and performer, blurring the boundaries between creator and subject. Warhol’s fascination with fame and identity permeated every aspect of his work, prompting audiences to reconsider their perceptions of celebrity and the art world. By showcasing his superstars in such an intimate and unfiltered manner, Warhol invited viewers to engage with the complexities of their lives, offering a glimpse into a world where art and life intertwined seamlessly.

In essence, Warhol’s films and performances were not merely artistic endeavors; they reflected a cultural moment that embraced experimentation and self-expression. The superstars, with their charisma and creativity, played pivotal roles in this artistic revolution, shaping the narrative of Warhol’s work and leaving a lasting mark on contemporary art. Their legacy endures, reminding us of the power of collaboration and the profound influence of identity and fame in shaping our understanding of art and culture.

Fame and Identity

Andy Warhol’s fascination with fame transcended mere artistic interest; it permeated the very fabric of his life and work. This obsession shaped how he portrayed himself and depicted his circle of “superstars,” a term he coined to describe the eclectic personalities who populated his world. These individuals were not merely muses; they embodied the avant-garde spirit of the 1960s, each contributing to a narrative that blurred the lines between art and celebrity.

The phrase “15 minutes of fame,” often attributed to Warhol, encapsulates his belief that everyone, regardless of background, would experience a fleeting moment of public recognition. This idea resonated deeply within the cultural landscape of the time, as television and mass media began to redefine celebrity. Warhol’s superstars—figures like Edie Sedgwick, Nico, and Joe Dallesandro—were living testaments to this phenomenon. They existed in a liminal space, straddling the worlds of art and notoriety, their identities intertwined with Warhol’s creative vision.

Warhol’s portrayal of his superstars was complex, reflecting both celebration and critique. He captured their essence in a way that highlighted their individuality while simultaneously commodifying their identities. For instance, Edie Sedgwick, with her striking looks and magnetic personality, became a symbol of the counterculture movement. Warhol’s films, such as “Chelsea Girls,” showcased her talent and allure while challenging traditional storytelling methods. The film fragmented narrative structure, allowing the superstars to express their identities and experiences in a raw and unfiltered manner.

The Factory served as a vibrant hub for these collaborations, a space where art, music, and performance converged, and where the boundaries between creator and creation were often blurred. Events like the launch party for Nico’s album “The Marble Index” exemplified this intersection. The party was not merely a music event; it celebrated identity and artistry, where the lines between artist and audience dissolved, allowing for a shared experience of fame and creativity.

Warhol’s exploration of fame had darker undertones. He recognized the transient nature of celebrity, often portraying it as both a blessing and a curse. His superstars, while celebrated, were also subject to the relentless scrutiny of public life. The duality of their existence—part artist, part icon—served as a poignant commentary on the implications of fame in contemporary culture. Warhol’s ability to navigate this complex terrain allowed him to create works that were visually striking and deeply reflective of societal dynamics.

In essence, Warhol’s superstars were more than figures in his art; they were integral to his exploration of fame and identity. Their stories, intertwined with Warhol’s own, created a rich tapestry that continues to resonate in today’s culture. Through them, Warhol captured the zeitgeist of an era and offered a timeless reflection on the nature of celebrity, identity, and the human experience.

The 1968 Assassination Attempt

On June 3, 1968, the vibrant atmosphere of The Factory was shattered by an act of violence that would forever alter Andy Warhol’s life. As he mingled with the eclectic mix of artists and personalities in his studio, radical feminist Valerie Solanas entered with chilling intent. Known for her provocative SCUM Manifesto, which called for the elimination of men, Solanas had previously been a marginal figure in Warhol’s world. However, on that day, she transformed from an obscure writer into a harbinger of trauma.

In a shocking turn of events, Solanas shot Warhol and art critic Mario Amaya. While Amaya escaped with minor injuries, Warhol was not so fortunate. The physical repercussions of the attack were severe; he was left with a permanent reminder, forced to wear a surgical corset for the rest of his life. This corset became a symbol of the vulnerability that lurked beneath his public persona, contrasting sharply with the flamboyant and confident artist the world had come to know.

The psychological impact of the assassination attempt was equally profound. Warhol, who had always danced on the edges of fame and notoriety, was now thrust into a realm of fear and introspection. The incident prompted a reevaluation of his lifestyle and artistic practices. The vibrant, free-spirited atmosphere of The Factory, once a sanctuary for creativity, began to morph into a more regulated environment. Warhol noted this transformation, crediting his collaborator Paul Morrissey for helping reshape The Factory into a “regular office,” marking a departure from its artistic haven toward a structured business model that prioritized commercial viability.

The aftermath of the shooting also catalyzed Warhol’s evolution as an artist. He could no longer afford to live in the reckless abandon that had characterized his earlier years. The incident instilled in him a sense of urgency and a need to adapt. As he navigated life post-attack, he began to explore the intersection of art and commerce with renewed vigor. This pivotal moment not only shaped Warhol’s outlook but also laid the groundwork for future endeavors, merging his artistic vision with the realities of a changing world. The assassination attempt, while traumatic, ultimately became a defining chapter in Warhol’s life, propelling him toward a new era of creativity and business acumen that would resonate throughout the art world for decades.

Business of Art

In the wake of the assassination attempt, Andy Warhol underwent a profound transformation that reshaped both his personal life and his approach to art. The shooting by Valerie Solanas at The Factory left Warhol with physical and psychological scars that influenced his future endeavors. The carefree, bohemian atmosphere of his earlier years was no longer tenable; the incident marked a pivotal turning point, prompting him to adopt a more structured, business-oriented mindset.

Emerging from this trauma, Warhol recognized the necessity of adapting to a shifting landscape. In late 1969, he co-founded Interview magazine with British journalist John Wilcock. This venture was more than just a publication; it represented a confluence of art, celebrity, and culture that aligned perfectly with Warhol’s vision. The magazine became a platform for the avant-garde, allowing him to blend his artistic sensibilities with the burgeoning media landscape. Through Interview, he delved into the intersections of fame and creativity, showcasing interviews with iconic figures and emerging talents. This initiative marked Warhol’s entry into the media world, solidifying his role as a cultural commentator.

Warhol’s entrepreneurial spirit extended beyond the magazine. He authored influential books, including “The Philosophy of Andy Warhol” in 1975 and “Popism: The Warhol Sixties” in 1980. These works provided insights into his thoughts on art, culture, and celebrity, reflecting his distinctive perspective on the world. In these pages, Warhol examined American society, offering a lens through which readers could grasp the complexities of fame and consumerism.

Additionally, Warhol embraced new media platforms by hosting television series such as “Fashion” from 1979 to 1980 and “Andy Warhol’s TV” from 1980 to 1983. These shows allowed him to explore the visual language of television, a medium rapidly gaining influence in popular culture. Warhol’s foray into television was a strategic move that kept him relevant in an ever-evolving landscape, showcasing his ability to adapt to contemporary trends while preserving his artistic integrity.

This shift toward a business-oriented approach did not diminish Warhol’s artistic vision; rather, it ensured his continued relevance in the art world and positioned him as a bellwether of the art market. As his works commanded astronomical prices, the lines between art and commerce blurred. Warhol emerged as a pioneer in understanding the value of art as a commodity, navigating the complexities of the art market with both shrewdness and creativity.

Throughout this period of transformation, Warhol exemplified a blend of artistic innovation and commercial acumen. He maintained his status as a leading figure in contemporary art while adapting to the demands of a rapidly changing cultural landscape. This evolution preserved his legacy and underscored his ability to resonate with audiences across generations, solidifying his place in art history. Warhol’s journey during this time stands as a testament to his resilience and adaptability—qualities that would define his enduring impact on the art world.

Evolution of Style

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Andy Warhol’s artistic style underwent a remarkable transformation, reflecting both his personal experiences and the shifting cultural landscape. This period was marked by experimentation with new techniques and collaborations that infused his work with fresh energy, allowing him to remain a relevant and influential figure in the art world.

One of the most striking innovations in Warhol’s later work was his embrace of oxidation painting. This unconventional technique involved using urine to create art, resulting in unique patterns and textures that challenged traditional notions of artistic creation. Warhol’s willingness to explore such provocative methods illustrated his relentless pursuit of new forms of expression, even as he navigated the complexities of fame and commercialism.

Warhol’s collaborations with younger artists were another significant aspect of his evolving style. Notably, his partnership with Jean-Michel Basquiat, a rising star in the Neo-Expressionist movement, produced over 50 large-scale collaborative pieces between 1984 and 1985. These works combined Warhol’s signature pop aesthetic with Basquiat’s raw, emotive style, creating a dynamic interplay that captivated audiences and critics alike. The blending of their distinct artistic voices rejuvenated Warhol’s creative process and positioned him at the forefront of a new wave of artistic expression.

Despite his growing commercial success, Warhol’s art during this period continued to grapple with serious themes. He juxtaposed iconic American imagery—such as dollar bills and electric chairs—with elements of celebrity culture, creating a dialogue that resonated with contemporary life. In works like “Dollar Sign” (1981) and “Sixteen Jackies” (1964), Warhol explored the intersection of consumerism and fame, reflecting a society increasingly obsessed with wealth and celebrity status.

Warhol’s ability to blend the comic with the serious further solidified his status as a pivotal figure in contemporary art. His works from this era retained a playful quality while addressing profound questions about identity, mortality, and the nature of art itself. This duality was evident in his later commissioned portraits of celebrities, where he transformed familiar faces into iconic representations, inviting viewers to consider the relationship between the individual and the public persona.

In essence, the evolution of Warhol’s style during the 1970s and 1980s was a testament to his adaptability and vision as an artist. He navigated the challenges of fame and personal trauma while continually pushing the boundaries of artistic expression. This period reaffirmed Warhol’s place among great artists and underscored his enduring relevance in a rapidly changing cultural landscape. As he embraced new techniques and collaborations, Warhol remained a formidable force, shaping the trajectory of contemporary art and leaving an indelible mark on the world he so keenly observed.

The Andy Warhol Museum

Located in the heart of Pittsburgh, the Andy Warhol Museum is a monumental tribute to one of the most influential artists of the 20th century. As the largest museum in the United States dedicated to a single artist, it not only houses Warhol’s extensive body of work but also preserves the legacy of a man who transformed contemporary art. Opened in 1994, the museum features an impressive permanent collection that includes paintings, drawings, photographs, and films, all reflecting Warhol’s multifaceted contributions to art and culture.

Visitors to the museum encounter Warhol’s iconic pieces, such as the vibrant Campbell’s Soup Cans and the haunting Marilyn Diptych. Each artwork invites exploration of the themes of celebrity culture and consumerism that Warhol masterfully navigated. The exhibitions delve into Warhol’s life, presenting a rich tapestry of his experiences, influences, and the cultural milieu of the 1960s and beyond. Curators thoughtfully arrange displays that highlight his artistic innovations alongside his role as a social commentator, emphasizing that Warhol’s work was as much about society as it was about art.

The Andy Warhol Museum serves as a cultural hub, fostering dialogue about the relevance of Warhol’s work today. Through educational programs, film screenings, and special exhibitions, the museum engages new generations, ensuring they understand Warhol’s exploration of fame and consumerism. His assertion that “In the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes” resonates powerfully in our current era, where social media amplifies the pursuit of celebrity status. The museum reminds us how Warhol’s insights continue to shape our understanding of fame and identity in an increasingly image-driven society.

Additionally, the museum is a testament to Warhol’s enduring impact on contemporary art. Artists today frequently draw inspiration from his techniques and themes, exploring the intersection of art and commerce in ways that echo Warhol’s legacy. By preserving his work and the context in which it was created, the Andy Warhol Museum plays a crucial role in ensuring that his influence remains vibrant and relevant.

As visitors leave the museum, they carry with them a deeper appreciation for Warhol’s genius and the cultural conversations he ignited. The Andy Warhol Museum stands not only as a tribute to the artist himself but also as a beacon of inspiration for future generations, reminding us that art can challenge, provoke, and ultimately shape the world around us.

Record-Breaking Auctions

Andy Warhol’s artworks have evolved into cultural phenomena, commanding staggering prices that reflect their artistic significance and the dynamics of the art market. Since his passing in 1987, Warhol’s pieces have not only maintained their allure but have also skyrocketed in value, establishing him as a bellwether of contemporary art collecting.

A striking example of Warhol’s market dominance occurred in 2013 when his haunting piece Silver Car Crash (Double Disaster) (1963) sold for an astounding $105 million. This sale marked a pivotal moment in the art world, underscoring Warhol’s position as a leading figure whose work resonates deeply with collectors and investors alike. The painting’s exploration of death and celebrity captivated buyers eager to own a piece of art history.

However, it was the sale of Shot Sage Blue Marilyn (1964) in May 2022 that truly set the art world ablaze. This iconic portrait of Marilyn Monroe fetched an unprecedented $195 million, becoming the highest price ever paid at auction for a work by an American artist. The auction, held at Christie’s in New York, was a testament to Warhol’s lasting impact and the insatiable demand for his work. The piece, emblematic of Warhol’s fascination with fame and consumer culture, encapsulates the essence of the pop art movement, making it a prized possession for collectors.

These record-breaking sales highlight the financial value of Warhol’s work and reflect the cultural zeitgeist surrounding his legacy. The auction prices serve as a barometer for the art market, revealing how Warhol’s pieces attract a diverse range of collectors, from seasoned investors to new enthusiasts drawn by his iconic imagery. The fluctuations in his market value illustrate the cyclical nature of art collecting, with new demographics eager to invest in Warhol’s legacy and the themes he explored.

Moreover, the rising prices of Warhol’s works speak to a broader societal fascination with celebrity culture and consumerism—two themes he dissected with a keen, prophetic eye. His ability to capture the essence of American life in the 1960s resonates today, as contemporary society grapples with similar issues of fame and identity in the age of social media. The ongoing interest in his art reflects a collective longing to understand the complexities of culture, identity, and the commodification of art itself.

As Warhol’s artworks continue to fetch record-breaking prices, they serve not only as valuable investments but also as enduring symbols of the cultural landscape he helped shape. Auction houses, once merely venues for art sales, have transformed into stages celebrating and reaffirming Warhol’s legacy, ensuring his influence remains vibrant and relevant in the contemporary art world.

Warhol’s Cultural Resonance

Andy Warhol’s fascination with fame transcended mere artistic interest; it permeated the very fabric of his life and work. This obsession shaped how he portrayed himself and depicted his circle of “superstars,” a term he coined to describe the eclectic personalities who populated his world. These individuals were not merely muses; they embodied the avant-garde spirit of the 1960s, each contributing to a narrative that blurred the lines between art and celebrity.

The phrase “15 minutes of fame,” often attributed to Warhol, encapsulates his belief that everyone, regardless of background, would experience a fleeting moment of public recognition. This idea resonated deeply within the cultural landscape of the time, as television and mass media began to redefine celebrity. Warhol’s superstars—figures like Edie Sedgwick, Nico, and Joe Dallesandro—were living testaments to this phenomenon. They existed in a liminal space, straddling the worlds of art and notoriety, their identities intertwined with Warhol’s creative vision.

Warhol’s portrayal of his superstars was complex, reflecting both celebration and critique. He captured their essence in a way that highlighted their individuality while simultaneously commodifying their identities. For instance, Edie Sedgwick, with her striking looks and magnetic personality, became a symbol of the counterculture movement. Warhol’s films, such as “Chelsea Girls,” showcased her talent and allure while challenging traditional storytelling methods. The film fragmented narrative structure, allowing the superstars to express their identities and experiences in a raw and unfiltered manner.

The Factory served as a vibrant hub for these collaborations, a space where art, music, and performance converged, and where the boundaries between creator and creation were often blurred. Events like the launch party for Nico’s album “The Marble Index” exemplified this intersection. The party was not merely a music event; it celebrated identity and artistry, where the lines between artist and audience dissolved, allowing for a shared experience of fame and creativity.

Warhol’s exploration of fame had darker undertones. He recognized the transient nature of celebrity, often portraying it as both a blessing and a curse. His superstars, while celebrated, were also subject to the relentless scrutiny of public life. The duality of their existence—part artist, part icon—served as a poignant commentary on the implications of fame in contemporary culture. Warhol’s ability to navigate this complex terrain allowed him to create works that were visually striking and deeply reflective of societal dynamics.

In essence, Warhol’s superstars were more than figures in his art; they were integral to his exploration of fame and identity. Their stories, intertwined with Warhol’s own, created a rich tapestry that continues to resonate in today’s culture. Through them, Warhol captured the zeitgeist of an era and offered a timeless reflection on the nature of celebrity, identity, and the human experience.