WAYNE THIEBAUD

Written by BEN BAMSEY

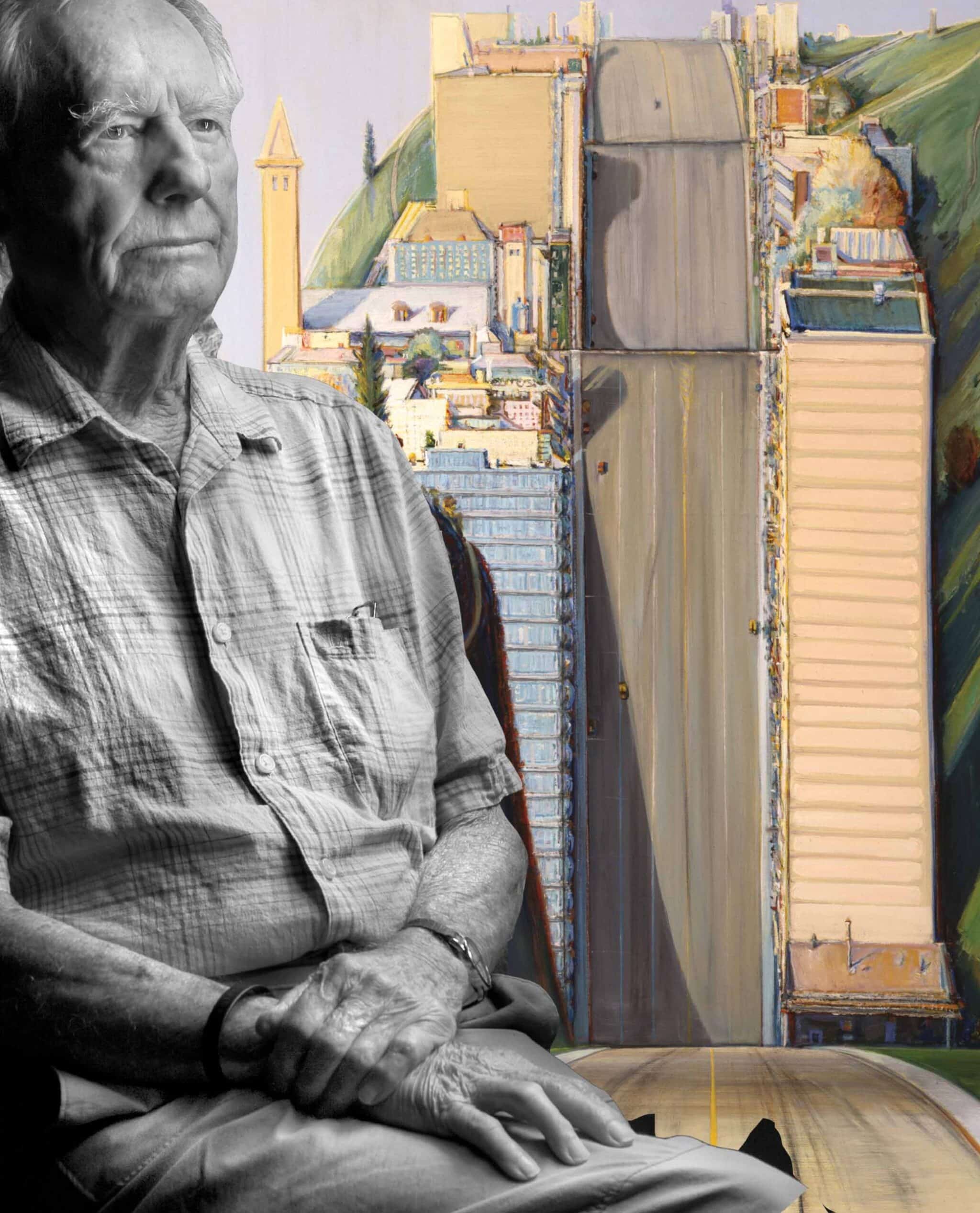

Photography by JESSE VASQUEZ

Wayne Thiebaud hates the word art. “It’s one of the dirtiest words in the English language,” he purges. “We all can say, ‘Oh yeah, that’s art. This is art.’ It’s a very abstract term that’s still developing. We’re still trying to find out what it is.” Art has an appetite that needs constant burping and an enormous bib because it tends to eat everything put in front of its face. Therefore, measuring greatness in its mega-conceptual world can be a very subjective task. Tastes vary. So do standards. Is it an ounce of ingenuity, a dash of technical skill or a cup full of corporate luck that makes one artist’s bread rise higher than another’s? Art’s x-rays have come back inconclusive and are now floating in formaldehyde.

But painting, now that’s a different story, one Thiebaud prefers to tell. Its encyclopedia reads much like a cookbook chronicling those that have added sizzle, seasoning or even sprinkles to its prolific palette. “Painters have to prove themselves,” Thiebaud concludes, acknowledging that the basic tenants of his profession were etched in stone some forty thousand years ago. But since those pre-historic days, just think of all the master chefs that have donned studio aprons to perfect painting’s meat and potatoes: Van Gogh’s brushstroke, Cézanne’s line, and Vermeer’s light; Renaissance men who could whip up just about anything like Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael; new flavor finders like Monet’s Impressionism, Matisse’s Fauvism or Picasso’s Cubism; and modern era painters that have borrowed from these handed down recipes but added a new ingredient, the vanilla extract in the pancake mix, if you will, like Ed Ruscha’s showcase of the English language, Josef Albers’s homage to the square and Ad Reinhardt’s rich blacks. It’s a four-course meal that has loosened many belts. But just as those satisfied bellies get up from the table and head for the recliner, their sweet teeth call out, “What about dessert?” And that’s where Wayne Thiebaud comes in.

His iconic, sugarcoated images have made us salivate for more than fifty years now. Pies, cakes and ice cream have made Thiebaud famous, but there’s a depth to his work that extends way beyond the high calorie count in his subject matter. First and foremost, he’s a painter’s painter, one who gets teed up as high as a golf fanatic when the phrase “The Masters” is brought up. The consummate teacher and student, he is awed by painting’s tradition and not ashamed in any way to identify the sources of his inspiration. “My world is one of crime,” he admits. “I steal from every artist around the world. I steal from the Japanese; I steal from the Chinese; I steal from de Kooning; I steal from Diebenkorn – and try not to insult them at the same time. I don’t want to copy them. It’s just that their work comes with a useful tool of generating possibilities as a painter.”

Van Gogh set so many standards with a paintbrush that just the mention of his name elicits certain software programmed in your mind. That kind of pinnacle in painting can no longer be reached, but developing a signature style in today’s world is the ultimate accomplishment. “Your ambition is to try as best you can to create a little different visual species,” Thiebaud says. “Museums are the bureaus of aesthetics and physical achievements. You go to the museum in order to check yourself against those standards.” Navigating the long road from studio easel to MoMA wall is a mental and physical grind unlike any other creative outlet. There are no child prodigies in painting – no Mozarts making masterpieces at age six. “Painting is a series of problems that you are trying to solve – base, color, design, composition and those intrinsic characteristics, rather than all of the things which happen afterwards extrinsically – expressions, individualism, subject matter, iconography,” Thiebaud explains. “It’s all important but, first and foremost for me, is the formal plan – if that isn’t there in some measure, it’s very difficult to achieve much.” Which is why perhaps the most profound statement that can truly be made about this artist is that: You know a Thiebaud when you see one.

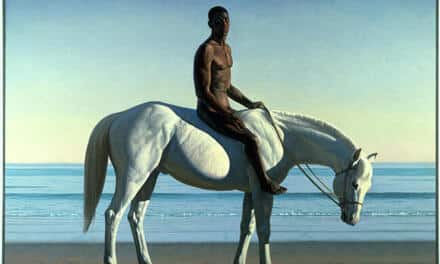

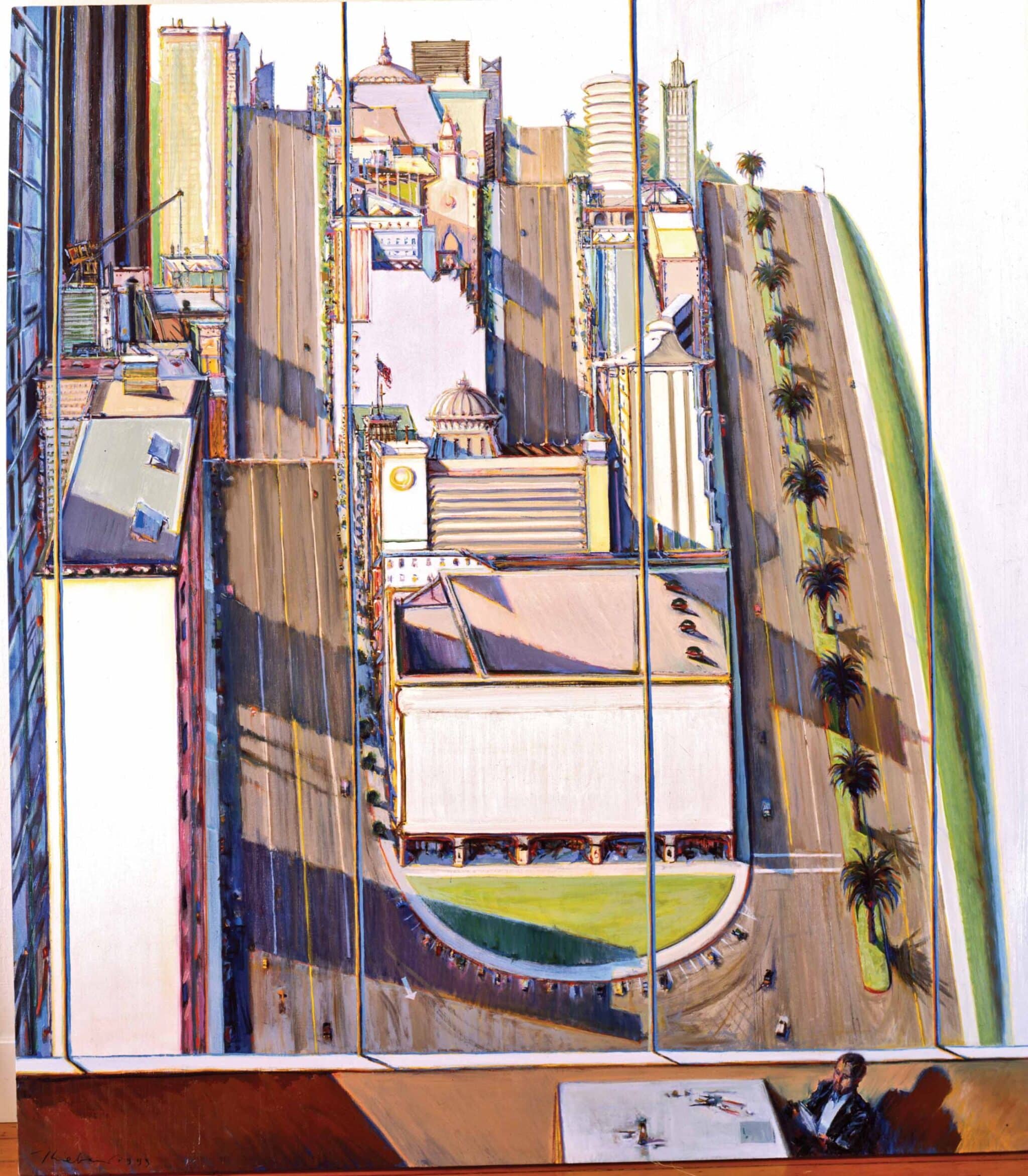

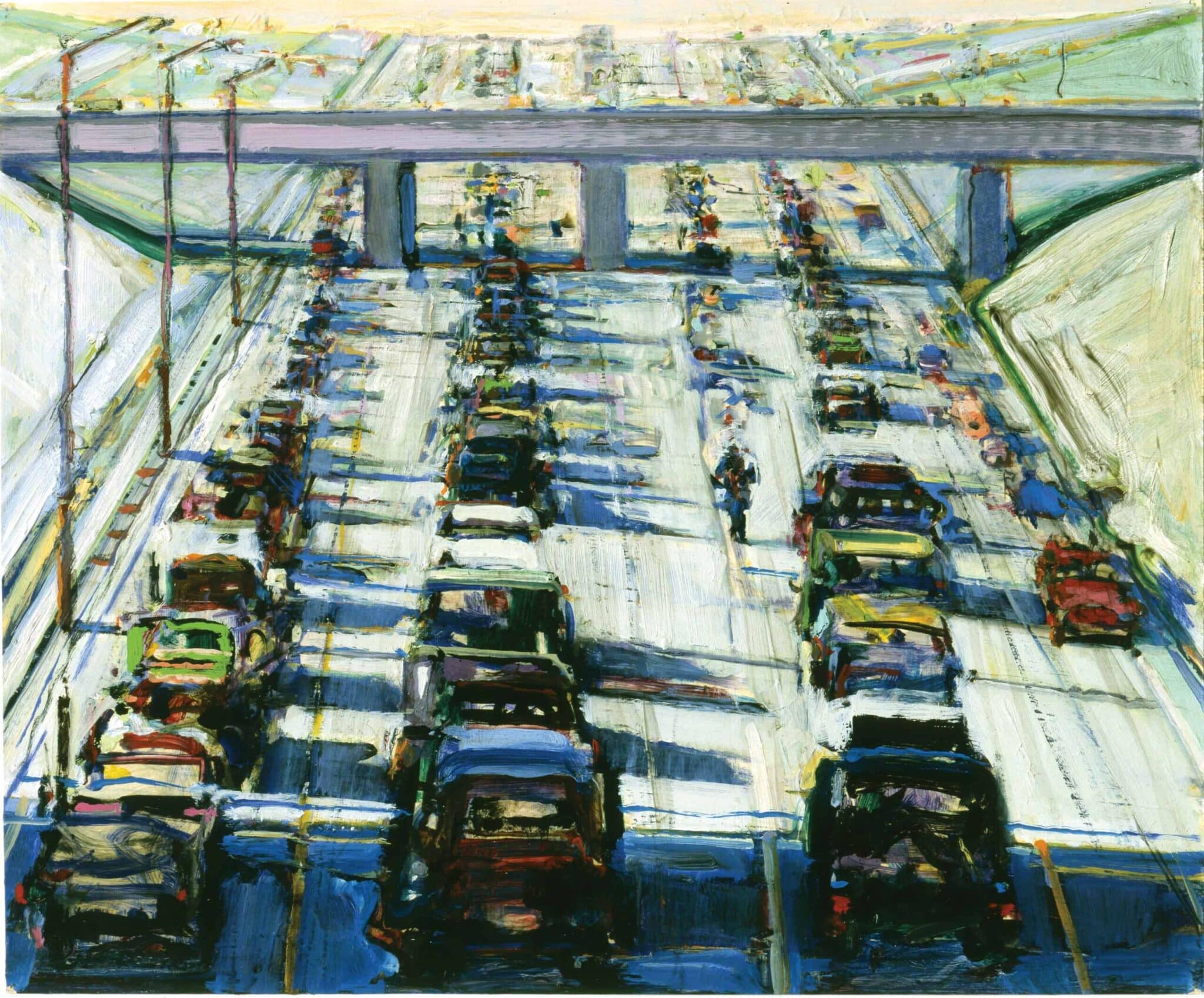

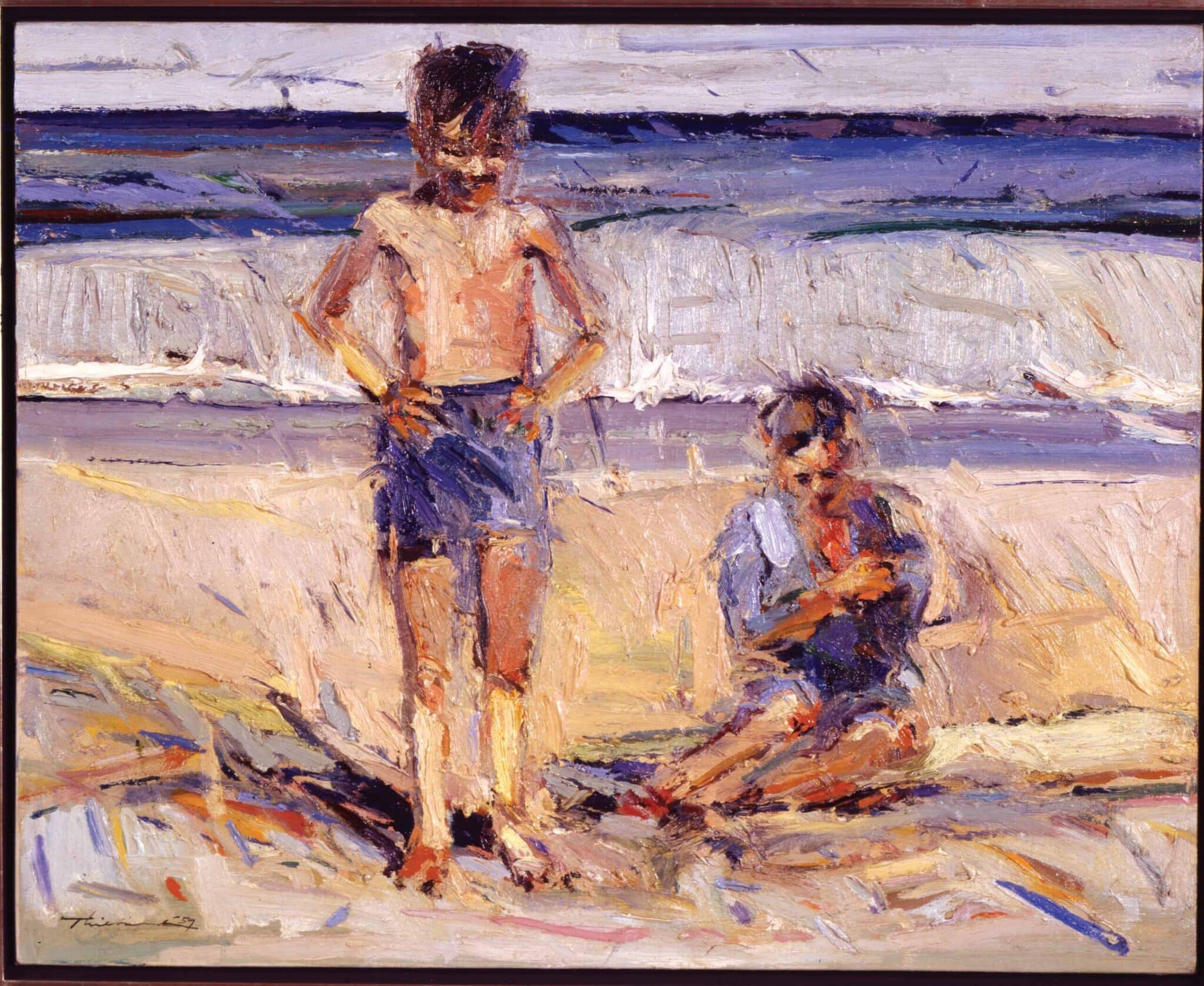

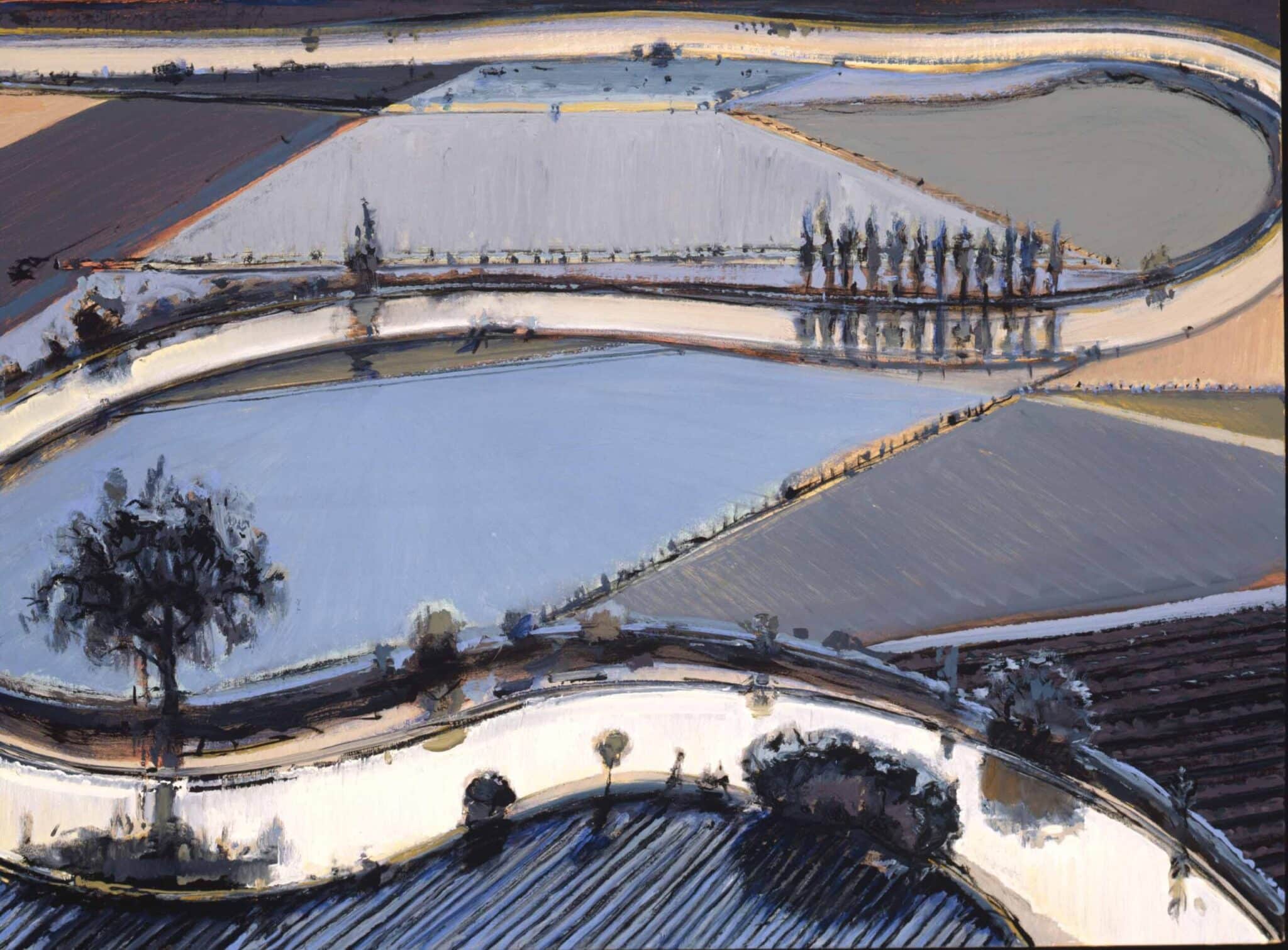

The Thiebaud aesthetic includes: the rich, smooth application of heavy textured and wildly colorful paint; simplified, yet varied forms that achieve isolation or order; and subject matter that glints, glimmers and glitters in a flawless dance with light and shadow. His most popular dish will always be desserts, but his still life work is actually very versatile: neckties, lipsticks, yo-yos, hotdogs, gumball machines and other examples of American food and consumer goods. The objects achieve Duchampian importance, yet rest comfortably in their simple Giorgio Morandi-style execution. Thiebaud’s talent goes so far beyond one pigeonholed artistic genre, however. His richly colorful and geometrically heightened paintings of northern California’s eclectic landscape balance realism and abstraction on a well-greased teeter-totter of viewpoints. His portrayals of the Sacramento Delta glow in the intense illumination of Joaquín Sorolla-type light while his San Francisco cityscapes enjoy the elevated significance of the Ocean Park series. Then, there’s the figure, and a body of Thiebaud’s work that speaks volumes in the subject’s apparent muteness. His expressionless portraits share similar reverie with Edward Hopper’s subjects, but contain David Park-like warmth.

Much like old Indian folklore, Thiebaud’s technical arrows come from a bag of tricks that have been handed down for generations. “I have been fortunate for having been taught by people who are kind enough to tell me how to do things… old sign painters, cartoonists, women’s fashion illustrators, wonderful graphic designers, typographers – they set the standard for knowledge in their medium.” Learning how to paint an “O” the right way was the first step towards understanding how to create a properly lit figure standing in space in proportion. Of course, getting from “A” to “Z” as a Realist sandwiched between two major artistic revolutions (Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art) meant Thiebaud had to have some serious fortitude. Having luck on his side didn’t hurt, either.

Thiebaud’s creative curiosity began with cartooning. He went from copying Krazy Kat as a kid growing up in Long Beach to working in Walt Disney Studios’ animation department when he was sixteen. He impressed co-workers with his ability to draw Popeye with both hands at the same time. Wayne grew up in a lower-middle class Mormon family during the Great Depression. While he had just one sister, there were enough uncles and cousins around to field a couple football teams. (His grandmother walked the plains with Brigham Young and had eleven children). So, when times got tough in the 1930’s, the Thiebauds banded together on a ranch in the Southern Utah flats. It was a great time for a kid with a big family, but most of Wayne’s childhood was spent trolling the Southern California beaches. His dad did everything from working on cars to milking cows because he had to. That resiliency trickled down. Wayne wasn’t a particularly good student, but was very crafty when it came to earning his keep. He lifeguarded, shined shoes and sold newspapers on The Pike – a carnival area where he traded his newspapers in order to watch Ossified Roy turn to stone and other freak shows. Wayne befriended an old black man known as the Wildman From Borneo who ate lit cigarettes and glass for money. The city also paid Wildman to scrape the sand each morning and haul away the trash. Wayne asked if he could be his helper, and as a reward, the 13 year old got to keep all the pennies they dug up. He made 35 cents a day.

In high school, Wayne washed dishes at restaurants, did poster design and worked on stage sets for theater productions – jobs that played significant roles in his development as a painter. As a teenager he knew that he wanted to be a commercial artist, but getting through WWII would have to come first. Thiebaud started out as a pilot in training with the Air Force, going first to mechanics school. That meant up-and-at-‘em at 4:30 a.m. inspecting planes. One morning, after tightening some bolts, Wayne stumbled by a barrack’s room. Inside, a bunch of guys were drawing pictures and making signs. So he knocked on the door. When they asked him to show them what he could do, Wayne didn’t hesitate. “I drew Goofy,” he says, “and I was transferred that moment. It probably saved my life.”

Becoming an official Air Force artist beat the heck out of flying missions over Axis occupations, but as the Battle of the Bulge drew near, Thiebaud and his colleagues were called to commando training. After thirty days of sweat, Wayne had his bags packed… “The Major came in, who is supposed to be a psychologist, and he gives us a lecture about the obstacles we were about to face in war. Then at the end, he says, ‘And don’t worry, a lot of you may be coming back.’” But again, as fate would have it, just before Thiebaud was about to get on that truck, he was summoned to talk to a high-ranking general. “And I thought, ‘Oh boy, what the hell have I done?’ But the guy says, ‘I understand you paint some pictures,’” Thiebaud says reenacting his coarse voice. “I said, ‘Well yes.’ He reaches in a briefcase and pulls out a picture of a woman. ‘That’s my wife. If you can paint me a picture of her, I can pull you off of this detail.’” Thiebaud spent the rest of the war working with Ronald Reagan in Culver City previewing training films. “God, I’ve been one lucky bugger.”

After his discharge, Thiebaud went to work as a poster artist and layout designer at Universal Studios, and later an illustrator in the advertising department at Women’s Wear Daily in New York. He then used the G.I. Bill to earn a diploma from California State College in Sacramento where he developed a newfound interest in the “finer” side of art. “I think it’s a bit pompous to call some things fine art and other things commercial art,” he says. “I like to use the terms applied research for painting and pure research for painting and drawing. To me, that is a nice distinction – the same exists between composing and performing. Not everyone can be a composer, but there’s a rich use of interpretation in performance.” Thiebaud’s Act I incorporated lighting effects he’d picked up in the theater and the draftsmanship of his ad days. He became a voracious reader of art history, and trained his eyes to see and his hands to mimic the common threads linking generations of great painters. He was up to his ears in ideas early on – printmaking, sculpture and public murals. His canvases were a hybrid of Cubism and Expressionism. When Thiebaud took his first teaching gig in 1951 at Sacramento Junior College, he was far from any major art center, but was well aware of the explosion of AE in New York. He made several trips to the Big Apple to taste the juice for himself.

Elaine and Willem de Kooning became good friends. Both revered painting’s past and potential, and they could talk about both at great depths. After a visit with De Kooning in 1956, Thiebaud became interested in the innocent, yet core, act of manipulating paint. “People are always trying to break the backs of paintings by expecting things which painting cannot do.” de Kooning told Thiebaud. “It’s just a painting. A God damned painting. Just a little thing you smear some stuff on. You just hope in the smearing that you haven’t insulted people that you’re asking to look at it.” In Thiebaud’s mind, de Kooning’s thoughts legitimized the idea of what good painting might do.

So he went home to California to smear. The concept reminded him of the gooey glazes that dripped from the bakery counters back in Long Beach. Color, shape, texture – desserts seemed to have it all. His first go-round was a pumpkin pie. As Thiebaud mixed the oranges and browns to create the color “pumpkin,” the absurdity of it all was not lost on him. “I thought, ‘This is so silly,’ I knew some would think, ‘Now this is an idiotic idea, and tricky, and obvious, and all of those things,’ and yet, I couldn’t leave it alone. There was just such sudden joy! I thought, ‘Well nobody’s going to pay attention to what I’m doing anyway.’” Of course, comedy is clarity’s best buddy, and thanks to Thiebaud, art’s serious side has grown some pretty hefty love handles over the years.

By the early-1960’s, his work had achieved tension, balance and grace… form first, objects pushed forward, relevant order. He’d been making statements about the perils and rewards of window-shopping, long before Warhol’s Brillo Boxes, Rosenquist’s canned corn and Lichteinstein’s Ben Day dots. But they all got big together, so it’s easy to lump Thiebaud in with the wave of Pop Artists. Many critics still do. But unlike Pop, Thiebaud’s canvases are not advertisements, and they are not ironic. In fact, he cautions against reading too much into any symbolism that can be found. “I’m not a card carrying Pop artist,” Thiebaud says. “I don’t like much of it.” It troubles him because he has too much respect for the original product designers. Although he has great admiration for the talents of Claes Oldenburg and Jasper Johns, he felt Pop as a whole, became more of a business operation than honorable painting. So while Pop took off, Thiebaud moved on. He became a professor at U-C Davis, alongside some of the great California game-changers: William Wiley, Roy De Forest, Robert Arneson and Manuel Neri.

Under a backdrop of West Coast creativity and the Bay Area Figurative movement, Thiebaud began tackling what he considered to be the most fundamental and most difficult genre – the human figure. Thiebaud’s people lack storylines. They are almost always contemplative and are without gestures of any kind. In fact, he often paints profiles and has even flipped subjects around so that all the viewer can see is their backs. The figures in their plain, open settings are the objects, in the same vein as his still lifes. In 1972,Thiebaud bought a small house on Potrero Hill in San Francisco. The blocky, old architecture and ski jump streets of the City By the Bay sent him scurrying for the studio. Squares and rectangles hold on for dear life in Thiebaud’s gravity defying verticals. Realism and abstraction dangle from that same slippery slope as light and shadow skate with the sun. His cityscapes provided street cred for Northern California concurrent with the ocean envy being drummed up by Richard Diebenkorn in Southern California. In 1997, Thiebaud parlayed the energy from his cityscapes onto the rivers and irrigation ditches of the Sacramento Delta, brilliantly exaggerating the vast forms and colors of the area’s farmlands. Thiebaud has spent the last decade dipping into and out of artistic themes much like Diebenkorn, who once told him, “The worst thing to do when you’re painting is to go headlong. You’ve got to stop and think, recover and try to avoid this obviousness. So many of us get these formulas or devices and get into kind of manufacturing a like product over and over and over again, because it’s commercially viable.” It’s the same message Thiebaud has passed on to hundreds of aspiring artists that have taken his classes at UC Davis. “When I talk to students I always want them to be aware. It’s too easy to become an employee of the art world, be consumed by it, and have it take you away from who you want to be.” He’s taught in a lab coat all these years, as if dissecting painting’s parts and spreading them out for students to examine. But he admits that he’s learned a lot from them, too.

Defining the word art is a pointless task, and frankly Webster should have better things to do. Art’s world has made room for controversial figures and kooky ideas, gimmicks and the gross. “Koons, Hirst and the whole development period after Pop, became a business enterprise, in my view,” Thiebaud says. “It dips in and out of the art world in a way, but for me is often terribly misguided in terms of the traditions that I admire and adhere to.” One of Thiebaud’s favorite anecdotes comes from Sir Ernst Gombrich, a writer and psychologist, who penned Art and Illusion in the 1960’s. Gombrich was once asked why he wasn’t interested in contemporary art. His answer was succinct and interesting, “Because it’s too easy to cheat in that environment.” Art’s tradition has soft borders, and like the United States, that has mostly been a good thing, providing freedom and opportunity for the dreamers. But to be a painter, and to create works of such dimension and interest that they grace the hallowed museum walls where The Masters have hung, now that’s one of the greatest achievements of the human enterprise.

Wayne Thiebaud has copied from the Masters because he cares that much about the craft. But in the process, he’s added his own icing on the legacy of painting – or at least, added some spit polish to the halo above its angel food cake. “I feel very privileged to be a part of that whole thing, however small,” Thiebaud says humbly. “The capacity of painters to make a world apart from this world will always amaze me. It’s a parallel world, in a way, which offers all sorts of records of human behavior – what we have been, what we are, what we might be. The fact that you take something that is flat, not moving, silent, and produce a world that suggests all of these records and possibilities – and to have learned how to have done that over a 40,000 year period of time – it’s magical. Just look at the light in one small Vermeer painting, and you can feel it. It really borders on the idea of a human miracle.”