David Ligare is one of the most creatively complicated men you’ll ever meet. He’s the 21st century tripartite combo of Socrates, Picasso, and Homer – a scholar, painter and classicist all rolled into one. He has an unquenchable thirst for knowledge and is driven by his philosophy.

David is an artist in every sense of the word who believes his craft is a matter of solving problems. While thousands of artists have already solved the problems of conceptual art, abstraction and realism, David’s been tackling the problem of narrative art since the 1970’s.

His paintings do more than just allude to history, they tell whole stories. His classically inspired art is also wonderfully contemporary. Through each carefully crafted painting the viewer is taken on an intellectual journey. While his light-flooded, pastoral settings are easy on the eye, it’s the invisible architecture underneath that marvel so many. Ligare balances order and chaos on the canvas and in the encoded life lessons within his art. His subjects are faced with moral dilemmas, in most cases, seeking belonging over self-righteousness and balance over choice.

A great illustration is “Hercules Protecting the Balance Between Pleasure and Virtue” (1993). In Ligare’s painting, Hercules is breaking up a fight between Virtue and Pleasure. Historically, Hercules had to choose between excessive luxury and responsible action. Most parents teach their children to pick the latter. But David sees it differently. His classicist beliefs tell him balance is the essence of quality living. So according to him, “Hercules must not choose one over the other, but must incorporate them both.”

Ligare’s also famous for balancing his canvas between the visual language of Greco-Roman history and the profound beauty of the Central Coast. It’s an anachronistic (out of order) approach that few have explored. David once wrote, “I believe in time travel, to wander freely through history rather than being inflexibly attached to the present.” While the central theme in his paintings is Greek classicism, his landscapes range from Big Sur and Point Lobos to the Pinnacles, the cliffs along the Salinas River, and Monastery Beach, among others.

For the past fifteen years, David Ligare has called Corral de Tierra home. It’s his own piece of paradise that he shares with his partner Gary Smith. Ligare longed to live, study, and paint there after he read John Steinbeck’s first short story, “The Pastures of Heaven.” Just like David’s paintings, buying a home and most everything he does with his life has a purpose.

In a few minutes he arrived at the top of the ridge, and there he stopped, stricken with wonder at what he saw – a long valley floored with green pasturage on which a herd of deer browsed. Perfect live oaks grew in the meadows of the lovely place, and the hills hugged it jealously against the fog and the wind….”Holy Mother!” he whispered. “Here are the green pastures of Heaven to which our Lord leadeth us.”John Steinbeck – The Pastures of Heaven

David starts most mornings the same way: a cup of coffee on the deck basking in the sunlight and magnificent view. The rolling, oak-studded hills of Corral de Tierra are bright green and littered with colorful, seasonal wildflowers. In the distance, off to the north and west, the breathtaking view stretches past the Monterey Bay to the Santa Cruz Mountains. There are often deer, cattle and sheep grazing in the open terrain.

David’s home is elegant. Everything is proper and neat. “Penelope” (1980) is his baby. She hangs gracefully on the wall in his living room. He’s just as proud of her now as he was when he finished painting her 25 years ago. She is David’s classicist darling and represents every fiber of his being.

Above the fireplace hangs a collection that would make any art historian jealous: a framed Picasso etching, a Cezanne, a Matisse, a Claude Lorraine, and a Carlton Watkins. Around the house – a sculpture by the New York minimalist Carl Andre and a couple of works by the German conceptual artist Joseph Beuys plus lots and lots of other works, ancient and contemporary.

His studio is adjacent to his house. Inside on an easel sits one of David’s well-known thrown drapery paintings. He’s sold or given them all away so he recently painted one for his own collection. Frames, paint, brushes, slides, books, paper – all kinds of art supplies clutter things up a bit. Windows and high ceilings bring in lots of sunlight – David can’t work without it. Right now, he’s getting ready for two still life exhibitions this year in London and Los Angeles. Some of the finished pieces are propped up against a wall on the floor. Amazing, when you consider each piece is worth between $25,000 and $60,000.

David has the look and vocabulary of a professor. His salt and pepper beard is neatly trimmed. He wears circular, lime green glasses and handkerchiefs around his neck when it’s cold. At age 60, he’s distinguished but not old. He speaks softly, but directly.

David attended Art Center College of Design in Los Angeles where he learned a lot about perspective drawing. Ever since, he’s gotten the life perspective he craves from studying classicism. He believes a classical education is the only way to be truly modern and progressive. It’s a philosophy similar to the old adage, “How can you know where you’re going, if you don’t know where you’ve been?”

David’s a bit of a phenomenon. He’s been able to support himself through his art his whole life. He started painting when he was four. At age five, his family moved to Manhattan Beach, California, from Illinois. And when he was 11 he sold his first painting. David still remembers, “Tommy Bailey’s mother bought it for ten bucks.”

The painting was a school project – a Paris street scene. He’d never been to France and essentially copied it out of a history book. But, even his approach back then gives insight into how David thinks. “I can remember being really fascinated with it… looking at it carefully, thinking, ‘Huh, these are wet streets,’ and trying to recreate that look of the wet pavement.” Apparently Mrs. Bailey thought David got it right.

After that, David’s neighbor commissioned him to paint a surfer on a wave. David Ligare was already in hot demand. He’d become obsessed with the outdoors and natural light. He spent much of his free time getting lost in the woods and experimenting with his Paint-By-Number kit. “I think it’s interesting, the whole business conceptually that someone actually made these laws breaking up all the colors so that you have, say, a gradation of the sky. It starts with the darker color above and lighter below. I remember thinking, ‘Wow! That’s why nature looks like that.’”

Ligare went to classes at Art Center while he was in high school. He paid particular attention to the theories of structure and began framing his own paintings within geometric lines. In 1963, after graduation, he took a backpacking trip to Europe before college. A train ride south into Athens, Greece, one night was all the classicist direction he needed.

“I remember it so clearly… I got a hotel in the Plaka and went to bed. The next morning, I got up, walked down the narrow hallway to the door at the end onto the street. I opened the door and was, like, HOT! BANG! Like you feel when you’re coming out of an air conditioned room into the desert. I turned to the right and up the street. At the top of it was the Parthenon on the Acropolis shining in the sunlight. It was a magical moment for me… something that took my breath away.”

On that same European adventure, Ligare camped on the southern coast of Spain, not far from the home of Salvador Dali. On a whim, he decided to drop by. Dali welcomed him in and they spent the afternoon together. It was the first time David had seen a professional artist’s studio. And David will never forget what he saw: inside, Gala, Dali’s wife, was working on one of Salvador’s paintings. At the time Ligare didn’t think much of it, but he did have lots to talk about with the famed surrealist.

They shared California stories. After all, Dali spent a lot of time on the Central Coast. He was quite well known for some of the wild parties he threw in Pebble Beach and Monterey. Dali didn’t go into much detail about the social life on the Peninsula, but he did go on and on about the wildlife. Dali said the gorgeous, little bay at Port Lligat in Spain near his home reminded him of the rocks and crashing sea at Big Sur. David was sold.

Ligare left Europe a changed man. He had Greek architecture and history on his mind, a trip to Big Sur to plan and lots to sort out. But first, Ligare went back to the Art Center in L.A. to get his degree. David continued doing watercolor landscapes in his free time. In 1965, he graduated from college. He had the classicist roots he needed, but before he could grow, an unexpected uncle dropped by and forced him to switch courses. “I got grabbed by the U.S. Army,” David shrugs. “I should have been more aware of that, how you can avoid this kind of thing.”

Surprisingly, David looks back fondly at his army days. He says basic training was an “amazing experience.” He passed all the physical tests with flying colors and said all the guns and bombs were like “being in an incredible movie.” His fill of the entertainment industry was just beginning, though. The army shipped David off to Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, where he worked as a graphic illustrator for United Armed Forces Television. He even read the news for awhile. David anchored “cold,” meaning he didn’t see the scripts in advance, and can remember the military writers putting all kinds of crazy things in them. They were the only kind of landmines he had to dodge in the army.

The TV gig was 9:00 – 5:00, Monday through Friday. He had his weekends to paint East Coast nature scenes and also spent a lot of time going to museums and galleries in New York. ACA Galleries took quite a liking to David and started showing his paintings. It was exactly the boost he needed.

In 1967, he was honorably discharged. The success he was having at those gallery showings simply reaffirmed his career path. But he didn’t want it permanently paved in New York. He was 22 now, and thought a cross-country trip back to California would be romantic. He spent a month sleeping under the stars and painting everything that caught his eye along the way. David thought back to the stories that Dali had told him about Monterey County. Those tales, along with the poetry of Robinson Jeffers and stories by John Steinbeck, were pulling him to the Central Coast. When David finally made it to the sleepy, serene town of Big Sur, he knew he was home.

Ligare still exhibited in New York, so he spent the next couple of years traveling back and forth. “I felt like I was in both of these worlds, this incredibly intense world of New York and incredibly isolated world of Big Sur with no TV or radio reception.” With nothing to do but paint and study, David began doing some soul searching. He wanted to do more than just landscape – by now he’d mastered the Pacific Ocean. He kept going back to the image of the Acropolis he’d seen that day in Greece. All sorts of ancient images swirled in his mind. One that stuck was something he saw frequently as he toured museums in Europe: old, marble sculptures from which the heads and arms had been knocked off somehow and all that remained was the draped torso. David Ligare was about to make it big.

By the early 1970’s, David was experimenting with white draperies. At first he painted them piled on a table with the sea in the background. He was painting with oil by now, and the finished pieces all looked so real. But David wanted more. “I thought it would be interesting to do drapery thrown in the air. So, I tried setting it up with a wire framework. But it didn’t look like a drapery thrown in the air; it looked like a piece of drapery hung on a wire.” That’s when the camera came in to the mix.

“I really did think that a camera was against the rules, that an artist just shouldn’t touch one.” But, David was set on doing whatever it took to get it right. So, he had a friend throw the drapery up in the air while he snapped photos. The camera was able to catch the outstretched drapery at its climax… that point where it’s suspended in air for just a split second before it falls back to the earth. This state of “betweeness” is an important aspect of classicism. He painted from the pictures and wanted the pieces to look like casual snapshots. But, in what would become a staple of David Ligare’s work, there was so much more behind them.

In fact, before Ligare ever put a brush on the canvas, he penciled in an entire structure of lines first. They related proportionally to the rectangle of the canvas. This was no easy task considering many of the works were 8 x 10 feet. “I wanted to have that underlying structure on top of which was this chaotic-seeming event happening. That’s the kind of balance I wanted.” David noticed that the balancing of opposites was another important principle of classicism. “In my mind the activity of the surface, including the tilted sea, represented Dionysius or Chaos and the underlying structure represented Apollo, the force of order and integration.”

The paintings alluded to classicism in that the drapery reminded him of the statues he’d seen in Greece. He also titled each piece after Greek islands. In 1978, he had a solo exhibit at Andrew Crispo Gallery in New York. The thrown drapery paintings were a major success. They were outside the plurality of contemporary art at the time and were flying out of the gallery at $10,000 apiece.

Ligare was exalted. He knew his next exhibit had to be even better. He decided then and there that “it was a more interesting problem to deal directly with the ideas of ancient Greece.” At the time, only one artist/critic was even talking about narrative art; Sidney Tillim called it “purposeful representation.” It was an idea that David latched on to. He wanted his paintings to tell stories, but he admittedly had a lot to learn. So, he started studying.

He fell in love with the works of two artists in particular: fifth century BC Greek sculptor Polykleitos and 17th century French painter Nicolas Poussin. Polykleitos truly is Ligare’s hero. His most famous statue, the Doryphorous, or Spearbearer, was a bronze figure that “embodied not just a man, but an idea, his Kanon,” according to David. “More than that, however, it outlined the concept of symmetria, which did not mean balance so much as it meant the integration of the varied parts of the body by a system of mathematical proportions.” In other words, it is the proportional integration of the diverse parts of the body.

When Ligare analyzed Poussin’s work he saw fullness: “Each figure, tree, and cloud had an integral relationship to the whole of the composition.” Ligare combined Poussin’s theory on landscape and Polykleitos theory on subject and established an interrelationship between the two. The images and ideas created by both of these artists contributed to what Ligare calls “recurrent classicism.” “Moreover, Poussin used these elements to tell stories that offered to the viewer moral or intellectual lessons. He often selected themes that suggested an individual’s potential for virtuous action.”

Ligare set rules for himself after studying these artists. For example, he borrowed the three basic elements (structure, surface, and content) from Poussin. The structure included the geometric design and proportion that he was already using. The surface signified the carefully realized look of nature itself, without additional layering of style or expression. Content meant that the painting had to have some kind of story to it, in other words, it was a narrative or allegorical story having something to do with philosophy.

Ligare also pledged to work exclusively with the late afternoon sunlight coming from the right- or left-hand side of the sky. “That way subjects are half in shadow, half out-of-shadow, giving them a really good sense of form.” The shaded and lighted surfaces were also in balance with his classicist philosophy. He insisted his paintings represent the idea of wholeness, borrowing Aristotle’s basic philosophy of beginning, middle and end as a description of whole systems. With these rules in place, the turning point in Ligare’s career was right around the corner.

1980: the year Ligare’s intentions caught up to his own intelligence. The lovely “Penelope” was born from studying the pages of Homer’s The Odyssey. She’s Ligare’s first unapologetic narrative and the first that dealt entirely with his classicist philosophy. The painting tells the patient and resourceful story of Penelope, the wife of Odysseus. As was his modus operandi, Ligare painted “Penelope” over a series of careful, structural lines. He also divided the canvas into thirds: the sky, the sea, and the stone. The structurally sound design, the cool, oil palette and the balance between sunlight and shadow are all strokes of brilliance.

A woman named Kathy Klausner was Ligare’s model. He thought she looked so much like his vision of Penelope from Homer’s book. David snapped several photographs of her sitting in Santa Barbara, where she lived. The painting he created spans centuries both in subject and substance. “Penelope teaches us to be quietly dutiful to an ideal even though it may take its time to be fully realized,” Ligare wrote to fans celebrating the painting’s silver anniversary. “Contemporary life wishes us to be always in the present, but as the poet T.S. Eliot wrote, ‘Time present and time past are both perhaps in time future, and time future contained in time past.’” After “Penelope” was finished, David stepped back and looked at her in all her glory and thought to himself, “this works.”

To David, “Penelope” also represents patience. It’s something he’d need as he tried to tackle another of Homer’s books. In the early 1980’s, David was beginning to exhibit all over the world, but the solution to The Iliad kept eluding him. After several starts and stops on “Achilles and the Body of Petroclus,” light bulbs came on after he saw Titian’s painting of the deposition of Christ. Through research, David found Titian actually borrowed inspiration from a Roman sarcophagus on the death of Meleager. So, while David borrowed from a Christian source, Titian borrowed from a Pagan source. In the end, it was a balance that gave David much pleasure.

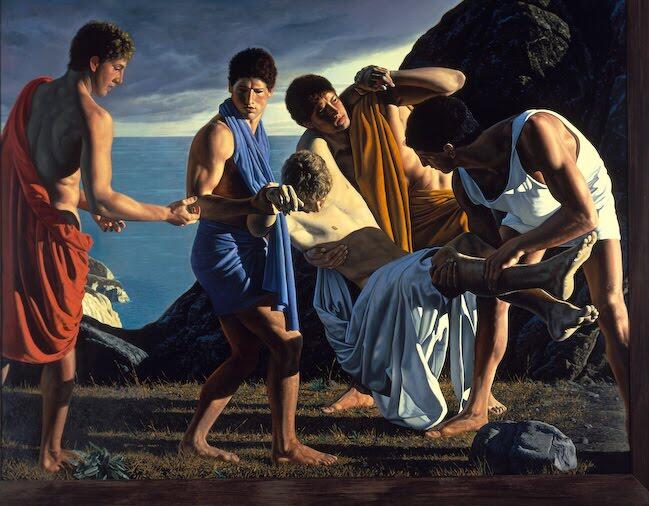

The finished piece is a staggering depiction of the pivotal point in The Iliad. Hector had just killed Patroclus, who he mistook for Achilles in the Trojan War. Achilles blamed himself because he allowed Patroclus to wear his armor. With his companion dead before him, everything pauses as Achilles surveys the tragic results of his selfish behavior. Borrowing a line from T.S. Eliot, Ligare calls this moment “the still point of the turning world,” it’s the “center of one of the most important tales in western literature.”

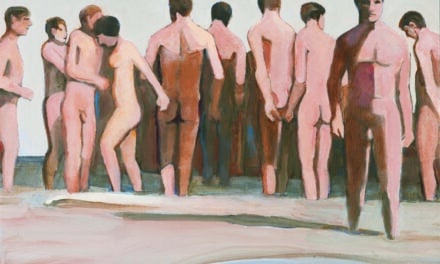

“Achilles and the Body of Patroclus” captures the essence of Achilles’ internal battle. David was teaching at UC Santa Barbara at the time and used students in his class to act out the scene. “I did the whole drawing of what I wanted it to look like including all of the structural lines,” David said. He got students to pose for it on a soccer field. He laid the drawing down, so the men knew what to do. “It made for an exhausting afternoon,” David said. “Over and over again I’d have them pick this guy up and carry him. I didn’t want it to look fake. I really wanted them to look like they were carrying him.” And it does, right down to the veins on the men’s feet.

Ligare’s paintings also reflect his belief in morality and putting others before one’s self. In “Landscape for Baucis and Philemon,” he uses Roman poet Ovid’s beautiful and humanistic theme of hospitality toward the stranger. It tells the story of gods Jupiter and Mercury dressed as beggars. After thousands of wealthy people turned them away, a poor, old couple named Baucis and Philemon took them in. The gods revealed themselves and offered them a wish. The couple asked to die together, because they didn’t want to take a breath without the loving company of each other. Their wish was granted, but before they died, the gods built them a temple and made them rich. The gods then flooded the valley of the inhospitable villagers. When it came time for Baucis and Philemon to leave this earth, they did so with one final embrace, and then were transformed into two intertwined trees, an oak and a linden. Those trees stood tall as an example of love, generosity, and hospitality. For David’s beautiful interpretation of this poem, “Landscape for Baucis and Philemon,” he used Lake Cachuma near Santa Barbara and the trees near Washington School in Monterey as models. The painting was purchased by the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut, the first art museum in the U.S.

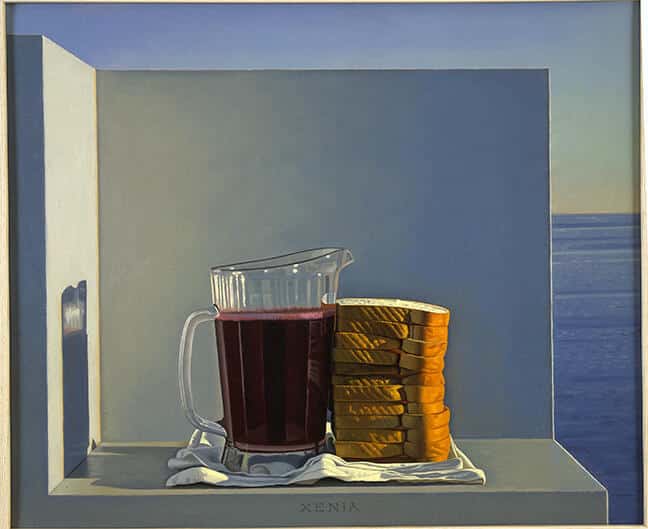

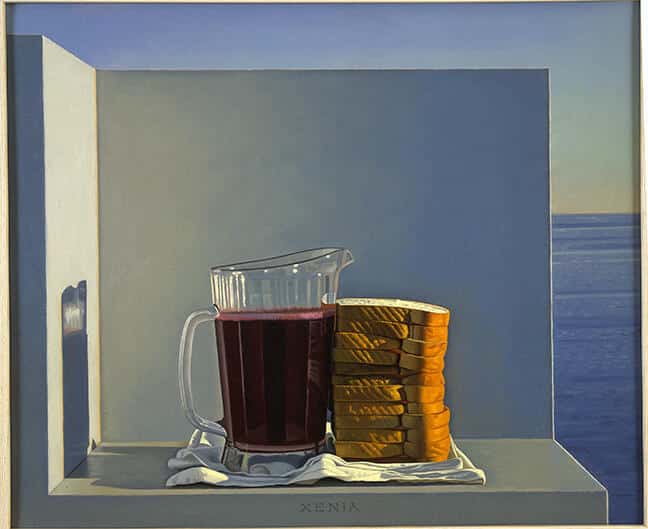

David practices the virtues he paints. For years he volunteered at Dorothy’s Place in Salinas, feeding the homeless. It provided him the inspiration to paint “Still Life with Grape Juice and Sandwiches, (Xenia).” David wrote, “It is thought that the first still life paintings were what the Greeks called ‘xenia,’ or food gifts, for strangers. When one had house guests in ancient times the custom was for them to dine with the family on the first night. Each night thereafter they would eat in their own room from a basket of food called a ‘xenia.’ As a subject for a painting it was a symbol of hospitality.”

David took that classicist philosophy and poured a pitcher of juice and made a stack of sandwiches and put them on a platform on his deck. He waited for the late afternoon light and took a picture. He carefully recreated the image on his canvas and painted the sea in the background. In his never-ending quest for wholeness, David took that same pitcher of juice and same stack of sandwiches down to the soup kitchen and passed them out to the needy. He currently serves on several charity boards.

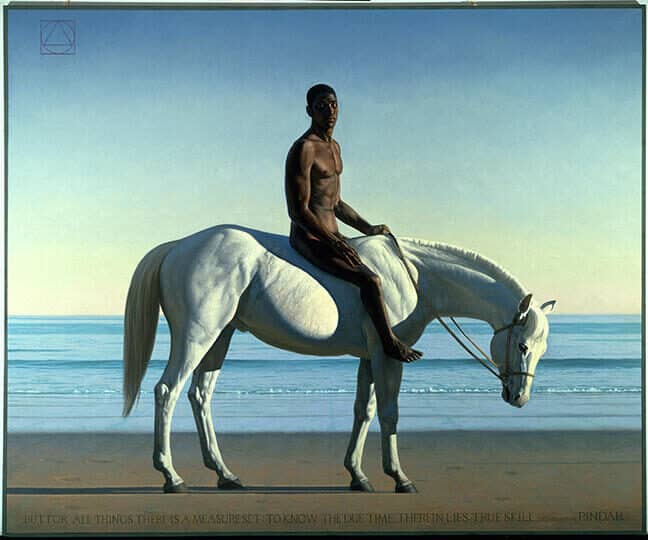

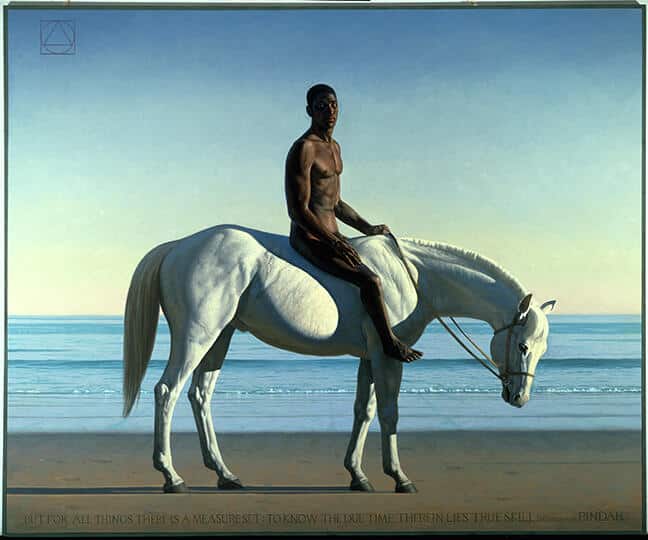

In 2000, Ligare did an exhibit called “Various Structures.” One of the standouts:”Areta (Black Figure on a White Horse).” Reproductions don’t do this piece justice. The painting is 8 x 10 feet, meaning the man is nearly life-sized (see page 27). David’s message in this painting is “the idea of integration as a multi-leveled metaphor.” Ligare has always argued that ancient Greece borrowed much of its heritage from other cultures. He says the sub-Saharan African influence might well have come by way of ancient Egypt.

David loved the contrast of a black man on a white horse and put them on a beach to show the harmony in diversity. In true classicist fashion, Ligare also wryly references Greek, black vase painting in this piece. He then borrowed a quote from one of Greece’s most famous poets, Pindar. The verse reads, “But for all things there is a measure set: to know the due time, therein lies true skill.” It’s a reference to athletics and the Olympian ideals of a raised bar in competition and sportsmanship.

As for the reason the man is naked, David loves the balance in the interpretation. On one hand, it’s an assertion of strength and confidence. On the other, he’s an object of desire. If you mold them together, it becomes a desire for strength and power. David also argued, “It can be read as a desire for structure, proportionality, measure, and integration. In other words, symmetria,” again referring to the sculptures of Polykleitos. The painting is now owned by the San Jose Museum of Art.

Since “Penelope,” David has spent the past 25 years doing more than 30 solo exhibitions in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, London, Rome, and elsewhere. He’s also been in dozens of group shows in galleries and museums around the world. Today, many of his paintings hang in some of the world’s finest museums, galleries, and private collections. His paintings have been reproduced in numerous books, journals, and magazines. The most popular reproduction: a poster featuring “Penelope” created by Oxford University Press advertising their philosophy books. It was an incredible compliment to Ligare’s work and ambition. David has given guest lectures and even taught semesters at such prestigious colleges as The University of Notre Dame, UC Santa Barbara, and The Prince of Wales Institute of Architecture in London.

David Ligare likes being original. He set rules because most other artists thought breaking them was the thing to do. What he paints and the way he thinks add to society. Ligare’s art began as a celebration of nature and evolved into an examination of life through landscape. Patricia Junker, curator of American art at the Seattle Art Museum, once wrote that Ligare’s narratives about ancient Greek history and the attractiveness of California’s Central Coast “reveal universal truths about humanity in a language that is clear, time honored, and accessible.” Ligare once wrote about his classicist views; they include “the integration of diversity, virtuous community participation, reverence for nature, the radical pursuit of knowledge and the embracing of the full implications of humanistic beauty.”

The whole story of David Ligare, like his paintings, is deep. His contribution to art and life is an eternal quest for knowledge and balance. Whether it’s order vs. chaos, virtue vs. pleasure, light vs. darkness, or ancient Greece vs. contemporary America, the answers to these problems are the integration of all their parts.

As for moving forward, Ligare continues to paint about 16 pieces a year. He sometimes works up to 16 hours a day getting ready for exhibitions. Front and center in his mind these days: literacy. “It’s not that people don’t read anymore, it’s what they read,” David worries. “I strongly feel that, as a society, we are in need of a renewed desire for knowledge. It is my belief that the potential rekindling of this desire is the job of culture. The common consensus is that culture reflects society but I believe that it can also help to direct it. I truly think that one of the most important things that can be done in art today is to reinvest paintings with a kind of literate life. The literate picture might just inspire people to read and to think more analytically.” Illiteracy, the number one problem David Ligare may spend the rest of his life trying to solve.

Written by: Ben Bamsey