ALL IN GOOD TIME

By Sheryl nonnenberg

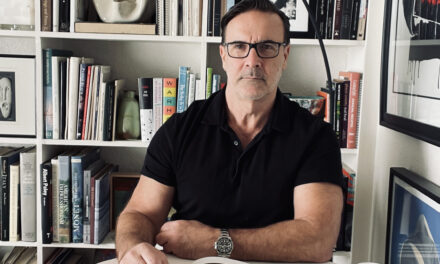

“Timing is everything,” Linda Christensen explained to me during a recent visit to her cozy Aptos, California studio. She was referring to an incident in her past when an art instructor at Cabrillo College pulled her aside and encouraged her to seriously consider a career in art. Apparently “not ready to hear it,”she chose instead to marry an up- and- coming young attorney, move to San Francisco and start a family. She gave birth to two daughters and spent the next twenty years enjoying all the outward trappings of the good life, but there was something profoundly missing. With the exception of a few open studios and helping out with art classes at her daughters’ schools, Christensen had not continued with her art. In 1985, she found the courage to resume her studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz, earning a B.A., and then a Fifth Year Graduate Certificate in 1988. In 1989, she divorced her husband and began working full time at her art. It proved to be a fortuitous decision; Christensen is now represented by two galleries (J. Cacciola in New York City and Sue Greenwood in Laguna Beach) and her work can be seen in a number of private and corporate collections. But spend a little time with the artist, look carefully at her large-scale expressive paintings, and it is easy to see that this is a woman who loves a challenge and who is not afraid to take chances, or to inspire those who view her work to do the same.

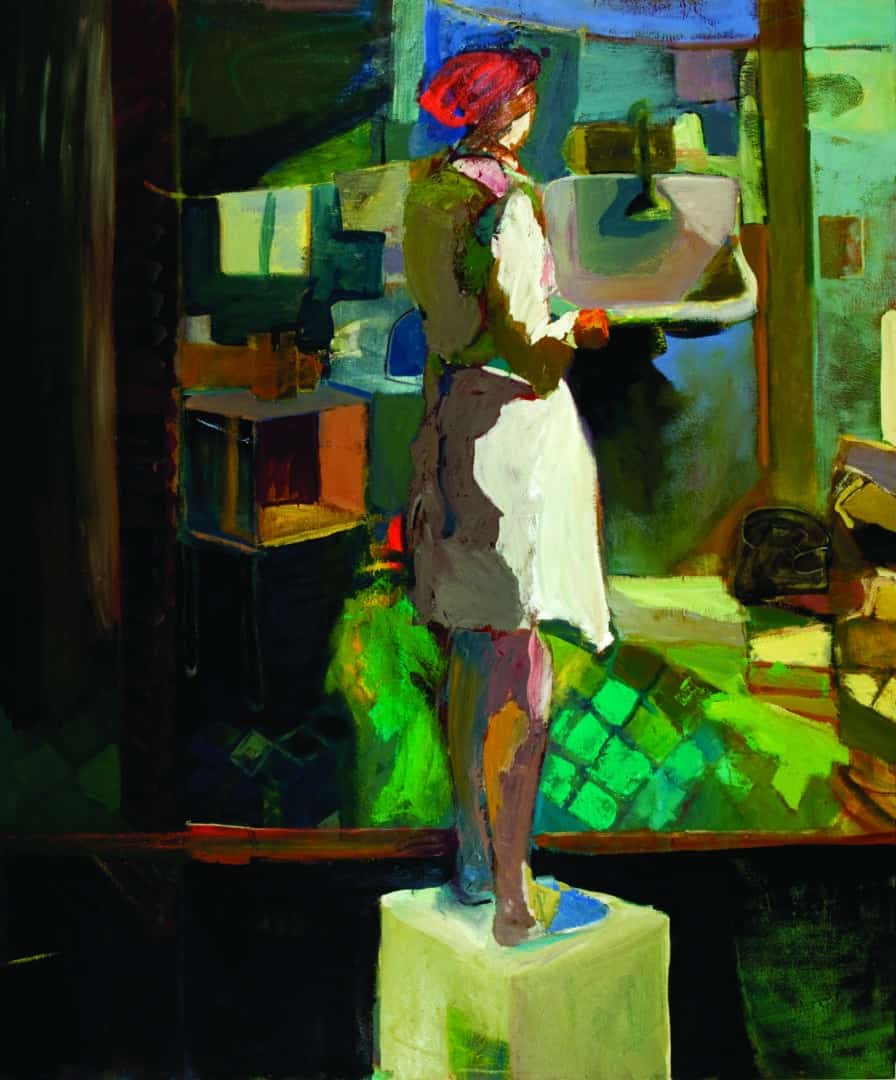

Linda Christensen grew up in Scotts Valley and recalls that she “always did art.” The family did not have money for expensive supplies, but her resourceful mother provided rolls of newsprint and Crayola Crayons. Even today, she says, “the smell of crayons can evoke so many childhood memories.” She attended Cabrillo College for two years then transferred to San Jose State, but left after just a year. After the twenty year hiatus from art, she entered UCSC as a “mature” student and found it to be just the nurturing experience she needed. Several courses there helped to shape her future style. The first was a printmaking class that resulted in a series of monotypes featuring a female figure. Entitled “When She Gets the Time,” the prints captured the determination required for women to do what they want and need to do, beyond the daily demands of home and family. Another influential classroom experience was the instructor who required that the students create 100 small canvases by the end of the quarter. Christensen completed 75 (more than anyone else) and it was a valuable exercise in working intuitively –not thinking, just doing.

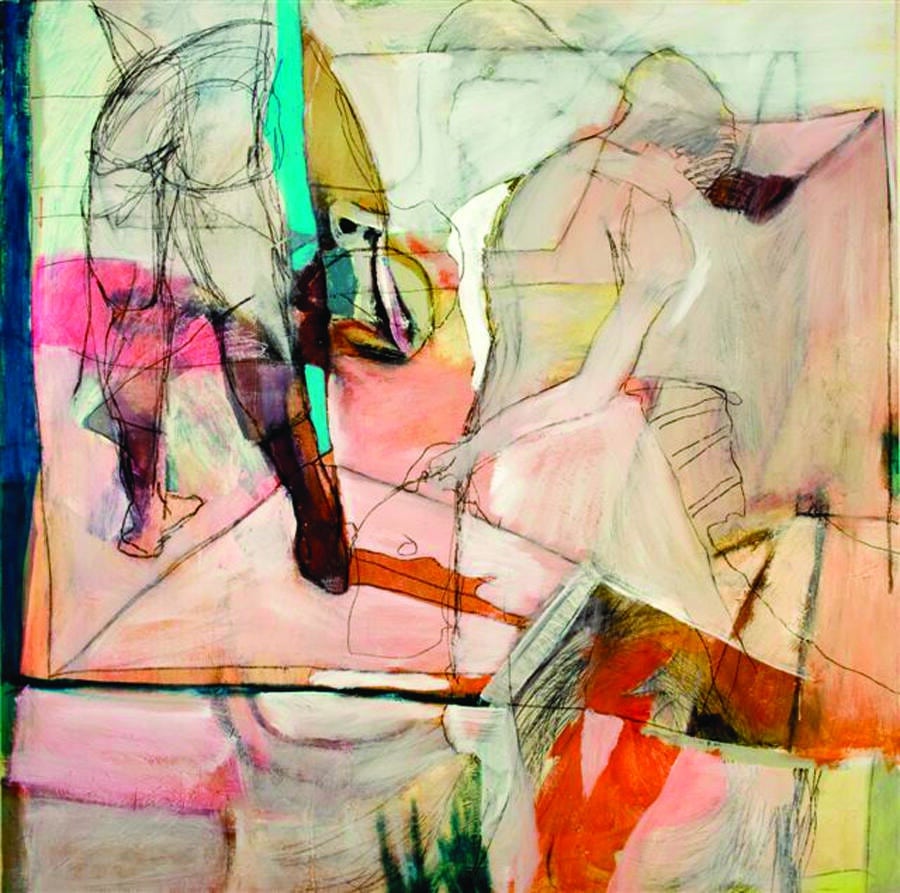

This intuitive approach, without prior plan or intention, has proven to be a very successful working method for the artist. But this is not to say that her work does not contain the various elements basic to an artist’s education. She did study life drawing (“important for the ‘bones’ of painting”) and she readily acknowledges that the grid is a mainstay in her work. Even when she attempted to make landscapes, there was always a roof top included. “It was something solid, she explains, and I need the grid for stability.” But apart from these techniques, the paintings are all about expressing emotion, and her inspiration comes from a wide variety of sources.

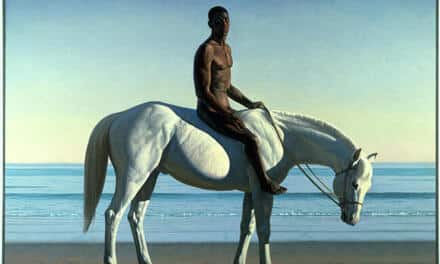

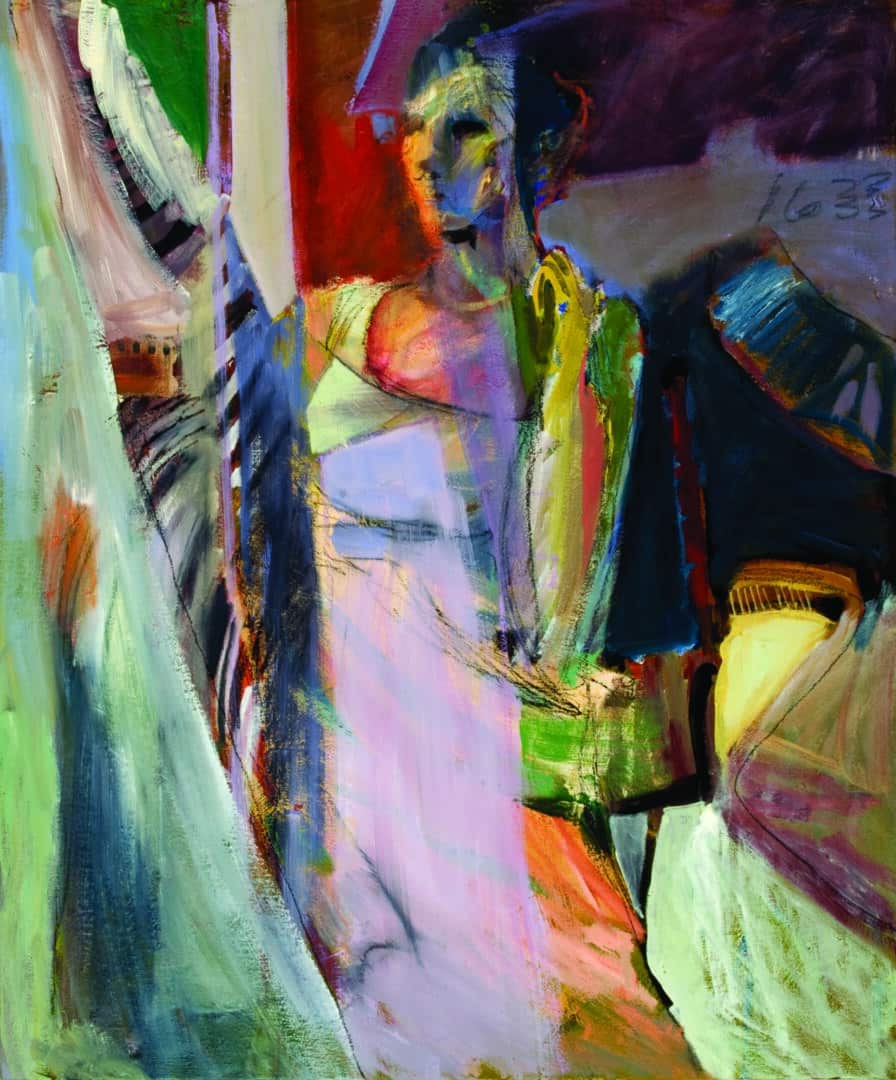

Early in her career, there were frequent comparisons with David Park, Richard Diebenkorn and other Bay Area Figurative artists. While she was flattered by the allusions to such groundbreaking artists, it was always more important for her work to reflect her hand and “to make it my own. “ Her signature feature is the female figure, often seated and captured in a moment of reverie, unguarded and unaware of being watched. As a guide for matters relating to composition and anatomy, Christensen refers to photographs of her daughter, Emily (“my muse”), that are tacked upon the wall of her studio. For the all-important variations of expression, however, the artist calls upon women she has seen in the local coffee shop or grocery store. Every excursion outside the home is an opportunity to observe a stranger, and then take that emotional quality back into the studio. She claims that this works for her because she knows, and can relate to, whatever she has seen, whether it is anger, sadness or just a quiet moment of letting go. (Men are never used as subjects, says Christensen, because of their lack of expression. “Just watch a guy talking to someone, standing with his hands in his pockets – they don’t reveal themselves.”) Even without clear delineation of facial features, or depiction of specific actions, there is a perceptible emotional quality to Christensen’s paintings. And we, the viewer, are encouraged to find the meaning for ourselves. As the artist explains, “I never want to walk you through it.”

On a table in the studio a rainbow of paint spatters, fresh from large cans that she buys from a distributor, give an indication of the importance of color in her work. Yet she explains that she never purposely begins a canvas with any color scheme or even an outline of a figure. It all begins with the simple application of paint, then evolves into a finished scene or is worked and reworked until Christensen is satisfied. Lately, she has been using graphite, oil pastels and stencils to distract her when she gets “stuck.” She works quickly and on several canvasses at once – usually to the accompaniment of black and white movies found on Turner Classics (“Dial M for Murder is a good one”) because the gradations of black and gray help her to see values in the colors she is using. New Age music plays in the background, compilations made for her by her daughter, Natalie, because “they remind me of visits with her and her family in Montana.” All around the studio there are books and magazines, and she shared several of her recent inspirations: catalogs about clay figures (“I like the variety of shapes”) and the Gees Bend Quilts, which she admires because of the original and unexpected uses of color. She is in the studio everyday, saying “I’d rather be here than anywhere.” And, in contrast to her younger days, when her art making was discouraged, Christensen now enjoys the total support of her husband who handles the day to day necessities and “zealously guards my studio time.”

Christensen credits other artists for helping her break into the gallery scene; Dennis Hare was especially generous in recommending her to a gallery in Laguna Beach. She participated in several group shows and her work came to the attention of a couple from Orange County who own a resort home in the desert. They acquired over twenty of her paintings and soon their friends began to buy her work also. Following her success in Southern California, Christensen began to seek representation in New York City. Again, an artist friend recommended her to John Cacciola, who has been not only a dealer but a mentor, says the artist. When asked what attracted him to Christensen’s work, Cacciola responded, “The paintings of Linda Christensen grab the eye with an immediacy that is uncommon. But more than this first visceral reaction, Linda’s paintings are a transcendence of mere technical display. They reveal themselves slowly, over time.” She is scheduled to have a show in New York in the Fall of 2011, and to be part of a three artist show in Laguna Beach in January. Although she has seen a decrease due to the downturn in the economy, her work continues to sell well in both galleries.

Before leaving, we spent some time with one of her favorite paintings, entitled “Kitchen.” The skillfully rendered figure has her back to me – she might be washing dishes, or looking out a window – but I know how she feels. I have been in that place and can imagine myself doing what she is doing and feeling what she feels. Perhaps it is this empathetic quality that Christensen so adroitly captures that makes her art so approachable. And, in an age where we are all constantly “on” (online, on the phone, on Facebook) such moments of quiet reflection are a rare commodity indeed. Yes, it’s all about timing – and being timely.

Sheryl Nonnenberg is an art researcher/writer who lives in the San Francisco Bay Area.