A JOURNEY INTO TWO WORLDS

By James W. Cameron

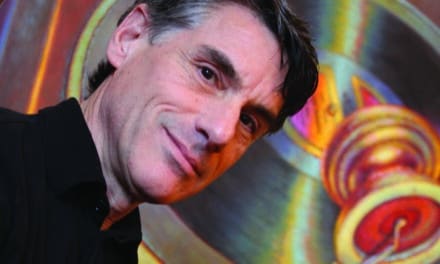

Jian Wang’s home in the Sacramento suburbs sits on a hillside at the end of a quiet cul-de-sac, a sprawling, multi-level, rustic structure surrounded by a variety of leafy trees and approached by a steep stairway. Repeated pressings of the doorbell go unanswered but a firm rapping on a window brings the host bouncing down an interior stairwell, a smiling, animated, and welcoming man with longish hair, a round face, and spectacles, to greet his visitor. The house is cluttered, a mélange of books, papers and paintings, paintings, paintings everywhere, stacked against walls and leaning on furniture, lying on couches and chairs, resplendent paintings full of color and passion. The host serves strong, black coffee and we settle down to a journey into two worlds.

Wang is apologetic, rubbing the sleep from his eyes, having stayed up late watching a television film the night before. He is thoughtful, alert and keen to sense the mood of the visitor, eager to talk but courteous and responsive to questions, a delightful and interesting conversationalist, a man comfortable with himself. The visit promises to be a rewarding one.

In the short span of twenty years, Wang has established himself as a leader in a regional art culture which can boast of artists like David Park, Elmer Bischoff, Richard Diebenkorn, Nathan Oliveira, Wayne Thiebaud, Gregory Kondos and Manuel Neri. With almost sixty solo shows in leading galleries across the country, a place in the permanent collections of several art museums, representation in hundreds of homes, corporate and public buildings, and a new and exciting presence in Asia, he is an American success story with a “Chinese twist”.

Although he began studying art at a young age in China, Wang came to practice his craft relatively late. He speaks of it in a kind of delightful Chinese-English patois. “I grew up in the time of China’s Cultural Revolution in the city of Dalian when the only art allowed was poster and billboard work used for propaganda purposes. I was always interested in art and worked at it every day after school and was selected for the Youth Art Academy. But I was never given a permit to take the art college exam. So I attended the Dalian Railway Institute and earned an engineering degree. Then I worked there as an instructor for the next four years. It looked like serious art was impossible for me.”

But Wang became acquainted with Marjorie Francisco, a retired Sacramento art teacher who was teaching English in Dalian and she was impressed with his painting and urged him to study art in the United States. “She spent a thousand dollars to get me here”, he says, “and I arrived in Sacramento with two hundred of her dollars in my pocket. Then she helped me get into Sacramento City College. She changed my life.”

A year and a half later, Wang was joined by his wife, Bonnie (not her Chinese name, he confides) and young daughter, Annie. As they are for many young people, particularly those from a foreign land, those early years were tough. Continued education and the cost of maintaining a family were difficult and Bonnie worked in a restaurant six days a week to keep it afloat. “She kept the family safe while I studied and worked at my art. She was wonderful.”

But when good fortune finally surfaced, it came relatively quickly. At the college, Wang studied for two years with Fred Dalkey who he describes as a mentor and friend. “He gave me a wonderful box of pastels his wife had given him for Christmas”, he recalls. Dalkey describes Wang as “an incredibly hard worker with tremendous drive, an energy way beyond my imagination. He took a number of classes from me and his promise was apparent from the beginning. He put together a tremendous body of work for his first show and that’s when the energy and drive became so apparent. Since then, his work has developed a rich, painterly look, romantic and dramatic. The application of the paint itself becomes an important feature.”

From Sacramento City College, Wang went on to the University of California at Davis. “For three years I studied under Wayne Thiebaud,” He had a tremendous impact, helping me to find myself as an artist.” In addition to Thiebaud, Wang’s tutelage included work with Manuel Neri, Roland Petersen, and David Hollowell. From there his journey took him to California State University at Sacramento where he earned his Master of Arts degree and was exposed to Jack Ogden and Oliver Jackson who served as his Advisor.

“Jackson gave me a sense of my limitations and helped me find the freedom to develop my own work style, what he called the mechanism of art. He was a great influence on me. I learned that art, like any other field, sports come to mind, has two goals. One is doing well with the materials; wanting to do better is a function of human behavior. The second is to bring a new experience to the viewer, joy, sadness, excitement. Both are important.”

In 1988, while a student, Wang had his first show at the Sacramento Artists Contemporary Gallery, a cooperative venture of Thiebaud’s where Dalkey, Kondos and other important regional painters showed their work. Wang did sixteen pieces for the show with the pastels given him by Dalkey, sold them all, and his career took off. Soon after that first show, he had solo shows at Gump’s in San Francisco and the Zantman Gallery in Carmel. The one man shows have proliferated since then along with a presence in a myriad of art museums and public and corporate collections, several publications honoring his work, and representation by galleries in New York, Washington DC, Atlanta, San Francisco Memphis, Kansas City, San Diego, and Santa Fe along with his home town of Sacramento. This past year, his work was seen in solo shows in Sacramento, Carmel, San Diego and Laguna Beach. A year earlier, Wang and his work were featured by KVIE, a Sacramento Public Broadcasting Television station and from March to September of that same year, a retrospective of his work entitled “Jian Wang: Two Decades In America” was hosted by California State University in Sacramento. A book with the same title was published in hard cover by the University Library Gallery of Sacramento State University. The publication includes a life history of the artist by Scott Shields, Chief Curator of Sacramento’s Crocker Art Museum and a brilliant selection of his work from the thousands of pieces he has painted.

While in Sacramento, Wang paints in a storefront studio on a busily traveled street dotted with strip malls offering commercial enterprises of virtually every kind. The interior is made up of two large rooms, spare and cold, and seemingly without inspirational value or influence. High ceilings offer abundant light to the front room which is where Wang works. A single easel adorned with a painting in process stands in the same room and on one wall is a large piece of industrial canvas, hung there to protect the wall since Wang paints most of his work there on canvases he suspends, standing while he works. A huge lump of oil paint rests on a palette on the easel, various colors seemingly intermingled. The room is littered with paintings in various stages of completion, some propped against walls and others lying flat on the floor. Wang estimates he has a hundred unfinished paintings crying out for his attention at any one time. “I have trouble finishing many of them”, he admits, “I have to push myself from time to time.” He ruefully points to one painting that has a slight mar on its face. “I can’t fix this one. I must have leaned something against it.”

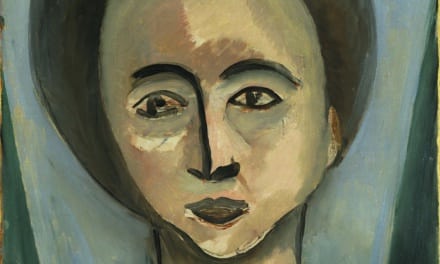

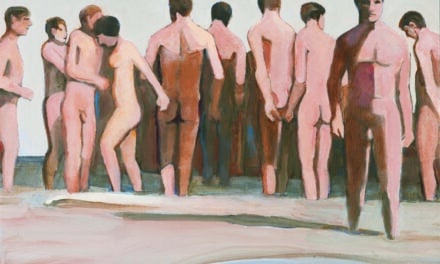

Wang takes long breaks from his painting to recharge and tend to his personal life and other aspects of his career but when he’s painting he’s a prodigious worker, churning out images at breakneck speed and working with great stamina hour after hour. In the back room of his studio, a rumpled, makeshift bed of blankets and sheets lies in one corner. “I never stay here overnight,” he says, “but I rest from time to time.” Wang is described by Crocker Curator Shields as “one of Sacramento’s most quintessential painters” part of the region’s “”second generation of the Sacramento school”, following in the footsteps of Thiebaud, Kondos, Dalkey, and their contemporaries. Wang describes his work as “expressionist realism ninety percent experimental and ten percent experience”; however described, it contains a unique style in which impasto plays a central role, thick paint layered upon layer with gestural brushwork, lush with vibrant color and visceral, sculptural relief. Wang labels it “first stroke painting”. He works quickly, mixing and blending paint on the canvas rather than on the palette and using only eight colors, equally at home in painting landscapes, figuratives or still lifes. He rarely prepares for the finished work with drawings, preferring to work directly from the subject. Mistakes are simply painted over through the application of more paint. The results yield paintings of vitality, energy, motion, spontaneity and in the case of his figuratives an unusual retention of the subjects’ personalities.

Late in 2007, Wang’s life changed dramatically when he was invited by the National Art Museum of China to prepare a show of his work to be displayed during the 2008 Olympics in Beijing. The show was entitled “Jian Wang, Full Circle” and was curated by the museum’s director, Fan Di’an. While Wang had revisited his homeland earlier, the invitation and the time he spent there revitalized his interest in his birthplace. From that point forward it became an integral part of his plan for the future and he stayed in China from 2007 until early 2009 “China is regaining its culture, a culture that seemed lost for a long while but is being revived on a grand scale,” he says. “The Chinese art scene has become the focal point of the world’s art scene. It‘s speaking with a new voice and the popular image of the day in China is contemporary art. Today, there are ten thousand artists in China.” As if to underscore Jang’s point, an art compound of a hundred galleries, two art museums and numerous teaching facilities has grown up in Beijing. Beginning in October of 2011, Wang will take part in a year of exhibitions throughout China, an experience he eagerly awaits.

Wang has established a home and second studio in Beijing and plans to spend a major portion of his life there, splitting his time between this country and his birthplace. “It’s an exciting time for the art world there and I want to be a part of it, “ he explains. “I feel the same excitement about art in China as the excitement that pushed me to develop as an artist. Sacramento is my home now but I will I will spend much time there in China.”

The reasons behind his success, this talented traveler on a journey into two worlds? Wang grows reflectful. “I was blessed with some talent and have worked hard to develop it further but I couldn’t have done it without the many people who have helped me along the way. They’ve all been wonderful but none so much as Bonnie. No, none of this would have been possible without her.”