the charmed life of theophilus brown

written by: Erin Clark

The Charmed Life of Theophilus Brown – it could have been the title to an F. Scott Fitzgerald novel. Our protagonist is a dashing young artist with immense talent and little direction. After enduring the horrors of World War II, including the soul sucking Battle of the Bulge, our hero hopscotches around the world, making the acquaintance of such cultural heavyweights as Pablo Picasso and Igor Stravinsky. He has a boyfriend on the Left Bank, and friends in high social places from New York to The Hague. The editor of ArtNews is a former classmate who introduces Brown to the likes of Mark Rothko and Willem and Elaine de Kooning. The parties are extravagant, the destinations exotic and the people famously beautiful, but there is something missing. A young Theophilus finds himself orbiting greatness without really touching it. A critical decision to head west to California and an encounter with a down to earth, no nonsense young man from Arizona changes everything. It is not love at first sight. The two young men are very different. One is gregarious and flamboyant; the other is quiet and reserved. But maybe opposites do attract. Perhaps it is fate. Theirs would be a love story spanning more than a half-century, and providing the foundation for two impressive artistic careers. Unlike the doomed characters of a Fitzgerald story, our hero escapes the pitfalls of privilege to live what can only be called a charmed life.

The journey taken when making a drawing – unlike trips with known destinations – can take us, if we are lucky, to an unfamiliar, even savage place. Armed with pencils, erasers, and a sheet of paper attached to a drawing board, we set out with optimism, even hopes. For here at the starting line, staring at the blank sheet of paper, we are still in the company of Rembrandt, Seurat or Degas. That blank piece of paper with its seemingly limitless possibilities goads us on, like the carrot suspended before a donkey’s nose. It scares us too.

Theophilus Brown

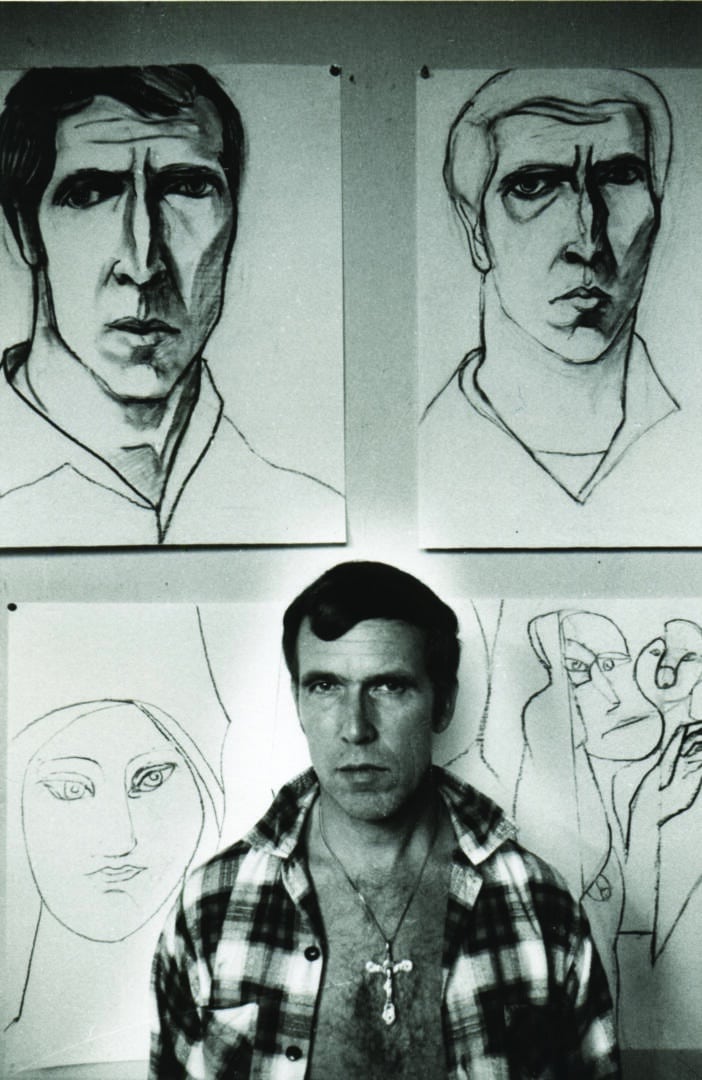

Brown’s artistic tendencies were nurtured early and often by his successful father. As an inventor and holder of more than 150 patents, he headed up the experimental department for the John Deere Company in Moline, Illinois. A superior draftsman in his own right, the elder Brown bought Theophilus his first sketchbook. “I remember I was about six years old and we were waiting for my mother who was visiting someone at the hospital across the river in Davenport. He took out a notebook and showed me how to draw houses across the street. Then he gave me my own notebook so I could make my own drawings. I kept that notebook for years,” Brown remembers. Such a simple exchange between father and son, but it helped form a strong foundation. “Drawing is fundamental,” Brown says bluntly. Throughout his career he has always made time for drawing sessions, often in the company of friends like Dick Diebenkorn, David Park, Paul Wonner, Don Bachardy, Elmer Bischoff, James Weeks, Beth Van Hoesen, and Wayne Thiebaud. Even today, Brown schedules a drawing session with live models once every two weeks. “I think with painters you can see if they can draw. Even with abstract work, there is a sensitivity that is good,” he says.

That drawing would later provide the foundation for figurative work that would secure Brown’s place in the vaunted Bay Area Figurative Movement. Like all artists, Brown lived in the context of his time. In San Francisco in the late 1940’s and 1950’s a robust return to figurative work was taking hold, led by a young David Park who, in 1949, famously took all of his abstract expressionist paintings to the Berkeley dump in one flamboyant rejection of the AE Movement that was all the rage in New York. Park returned to representational painting. He opened the door, and many other artists such as Elmer Bischoff, Nathan Oliveira, and Richard Diebenkorn followed him through, eventually leading to a stylistic movement with the figure as its cohesive glue. But it wasn’t so much a rejection of abstract expressionism as an integration. These painters took the lessons of AE and applied them to figurative work – a fresh approach that led to some of the most dynamic art of the mid-century. Theophilus Brown came of artistic age in this time and place, becoming one of the marquee painters associated with the “second generation” of Bay Area Figurative artists. And it all started with a gift from father to son.

His drawing talent was evident even as a child. As a youngster, he was one of the winners of a prestigious competition meant for adults. “When I was eleven I did a charcoal drawing of my father – a profile view. He was asleep, reclining in a chair after supper. He liked it and framed it, and entered it into an annual contest at the Davenport Art Museum, which was juried by Grant Wood (part of the Regionalism Movement and best known for the iconic painting, American Gothic, that now hangs in the Chicago Art Institute). I won third prize! When it was announced and this little kid walked up the aisle, it caused quite a sensation. I remember reaching up to shake his (Wood) hand, and he reached down. It was quite a thrill,” Brown laughs, retelling the story as if it were yesterday. And that’s the thing about Theophilus Brown – at 90 years young his mind is still sharp, and he remains a wonderfully detailed storyteller.

Brown is one of those enviable people who make the best of every opportunity. Wanting to go to art school after his prep school years, Brown instead acquiesced to his father’s wish that he attend an Ivy League University. Yale got the nod, and Theophilus decided to pursue a degree in music because the art department was “archaic and yet to be modernized by Joseph Albers, while the music department was excellent.” It speaks volumes that Brown had the talent to be choosy, but that is part of his life story. He has always embraced all of the arts; music, painting, theatre, literature, and poetry have all been part of his passion.

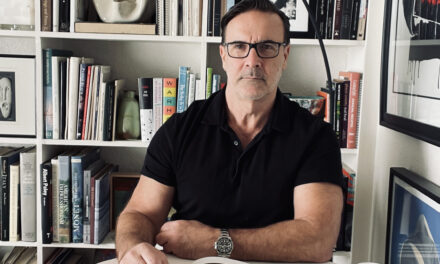

His simple, but elegant, apartment in San Francisco is a testament to his eclectic cultural tastes. The living room is dominated by a grand piano that he plays every Thursday night with an accompanying violinist. There is art on the walls, of course, but it’s not overdone. A simple day bed doubles as a sofa with his many photo albums stored in drawers underneath. Books are neatly piled on a bench near the window, which offers spectacular views of the city. He likes the downtown location because it’s just minutes to his studio, where he still works every day. With his bad knees and advancing age, he relishes the proximity. His friend and colleague, artist David Ligare, describes the home as a “refuge from the craziness of the modern world. There is no computer, but there is a quietness and timelessness that is also reflected in the figure studies and paintings that he has done for so many years, as well as the abstracted industrial scenes. No matter what he does art wise, and in conversation, there is a deep background of knowledge, experience and wonderful wickedness.”

Brown’s now famous joie de vivre was severely tested during the war years. He was drafted just two months after his college graduation, and would spend the next four and a half years in the middle of some of the most ferocious fighting of World War II, including the Battle of the Bulge. Admittedly, Brown was not a natural soldier. “I hated it,” he says simply. “I went from private to corporal in four and a half years. I don’t know anybody who rose so little. Being a graduate from a college like Yale was just poison for the old sergeants. They were not kind to me.”

But he endured, and along the way gained perspective he otherwise might never have found. “I like what Norman Mailer said about the war,” says Brown about a period in his life he rarely talks about. “Mailer spent two years in the army, and he said, ‘They were the worst years of my life, but the most important.’ That’s how I feel about it, too. It was a big corrective for me. I had lived a very privileged life. The war put things into perspective for me.”

When it was finally mercifully over, Brown took full advantage of the GI Bill, splitting his time between New York and Paris theoretically to study painting, but he admits that he spent very little time in a classroom. He did, however, travel in elite circles, meeting some of the era’s biggest cultural icons. Sometimes the introductions were planned, but more often seemingly chance encounters led to great adventures. Two of the best stories involve Pablo Picasso and Igor and Vera Stravinsky. Brown and a friend, Susan Kaufman, who would later write Diary of a Mad Housewife, were in Antibes to see the Picasso museum. They never expected to see the man himself. “We were going up the steps to the Grimaldi Museum, which had been converted into a Picasso museum, and there he was – Picasso, Francoise (Gilot) and his entire entourage. I had a letter of introduction from Mary Callery (New York sculptor) that I thought I would never use. I went back to my hotel, pulled out the letter and rushed back. I gave it to Picasso and he invited us to follow along. We went through the whole museum together. He was very funny, “ Brown remembers. “I saw him again with Mary in his Paris studio, and I once met him on the street. He had rock star status, so for a young artist it was quite something. Francoise once asked him (Picasso) why he was so nice to strangers and so awful to her, and he said, ‘Because they don’t matter.’” Brown laughs as he tells the story, still enthralled all these years later. It may not have mattered much to Picasso, but it made a huge impression on a young artist.

“The depth and solid consistency of Theophilus and his art is impressive. His familiarity with modern movements from Cubism onward is evident, but always with a classical regard for line, composition and the magic of the human figure. His keen mind and deep interest in music and literature pepper his conversation with astute observations, witticisms, and tantalizing tales. Stories flow of Stravinsky, Rothko, de Kooning, Thorton Wilder, Christopher Isherwood – all whom he knew well. This same intelligence has informed his remarkable drawn and painted forms for nearly seven decades.”

Gary Smith

The other act of random encounter actually led to a life-long friendship. Brown met the legendary composer Igor Stravinsky and his wife at a dinner party in Santa Fe in 1951. “They were in town one night, so it was one chance out of a billion that I would meet them,” Brown says, “I certainly never expected to see them again.” The next summer Brown attended a music festival in Paris. Walking home along the Left Bank, he passed a crowded café where he spotted Igor and Vera Stravinsky. Positive that they would not remember him he continued along until Vera’s voice pulled him back. “Aren’t you even going to say hello?” she shouted. Theophilus quickly returned to the café. Introductions were made all around and then came the invitation of a lifetime. The Stravinsky’s were going to Holland the next week for a festival honoring their music. Would Theophilus like to come? They were staying at a hotel in The Hague, and the Queen was providing a car and driver! Brown jumped at the chance. “I thought, ‘I’ve never been to Holland, so why not?’ I spent the whole week with them. It was marvelous for me. When we took them to the airport to fly back to America, the chauffeur then took me back to the hotel so I could settle my bill and return to Paris, but they told me the Queen had taken care of it,” Brown adds as an exclamation point to the story. He returned to Paris that day, and made plans to have dinner with a friend who brought another American along, as well. That man was Samuel Barber, an American composer who would one day win the Pulitzer Prize for music. It was in Brown’s words “a dizzying time,” but change was on the horizon. Brown was restless. Surrounded by greatness was not enough. He needed to find his own voice. “It was time,” he says bluntly. “High time.”

Thinking he would eventually teach, Brown enrolled in the fine arts graduate program at the University of California, Berkeley. The faculty was stacked with fine instructors – great artists in their own right, but it was another student who first caught Brown’s eye. Paul Wonner and Theophilus Brown shared three classes, and although Brown noticed him right away, Wonner wasn’t interested, at least not initially. “He was hard to know,” Brown says, “and he thought I was a terrible snob. Maybe I was.” Eventually, though, the two got together and the relationship provided emotional stability necessary for both to pursue their artistic aspirations. They shared a studio in downtown Berkeley and settled into the art community. Richard Diebenkorn had a studio in the same building. He and David Park, Elmer Bischoff, Nathan Oliveira, Wonner and Brown would all get together for drawing sessions. “We all liked each other,” Brown remembers. “Diebenkorn and David Park were very close. They would good-naturedly insult each other all the time. They had a great rapport. They all knew each other long before we came on the scene, but they were very accepting.” With that kind of talent milling about, the influence of one artist on another seems inevitable, but Brown says it was more inspiration than influence. “No one was copying anyone else, but we were motivated by each other.” As it turns out it was one of the most influential and prolific periods in the annals of Bay Area art, but at the time, the men and women involved were unaware of their eventual place in history.

Brown was, at the time, working on a series of paintings that he had started in New York. “I would cut out black and white photos from the sports section of the Sunday Times because I liked the unified action. I don’t know anything about football. I just used these photos as a kind of kick off. I wasn’t doing something literal,” he explains. The convergence of color, form and figure clearly show the influence of abstract impressionism, but just as incisively demonstrate Brown’s embrace of the figure. The “Football” paintings attracted the attention of Life Magazine, and following the publication of a full color spread, a gallery in Los Angeles contacted Brown about representation. By then Wonner and Brown were teaching at the University of California, Davis, and were only too happy to relocate to the land of sunshine and cultural celebrities in Southern California.

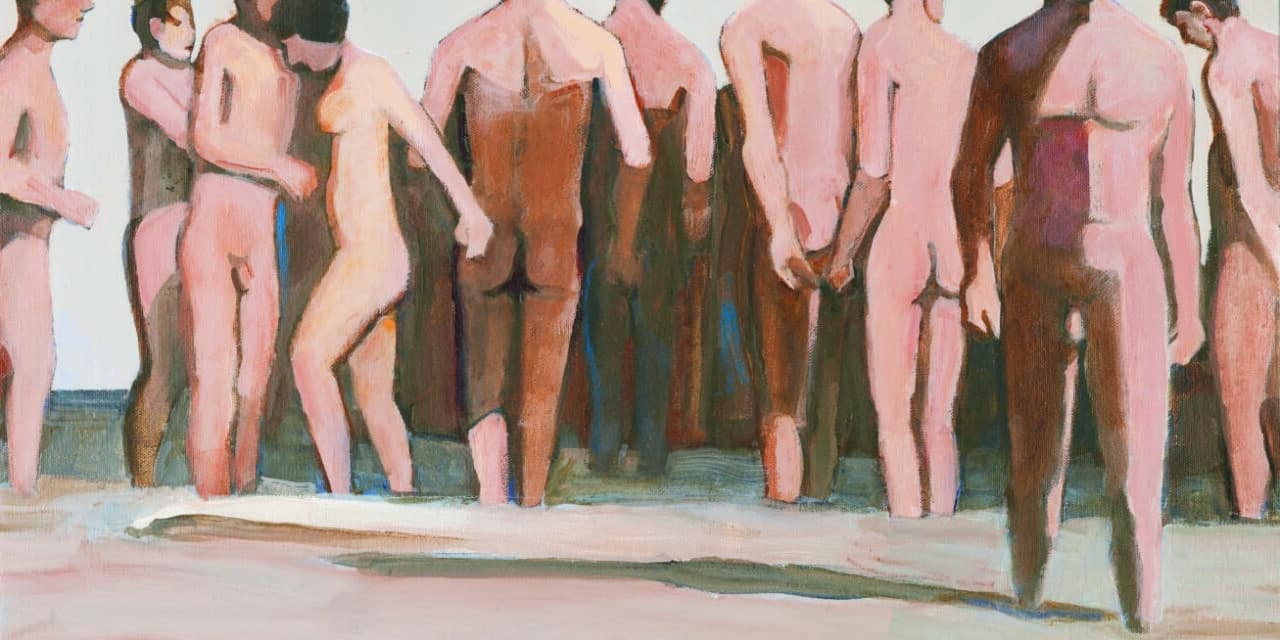

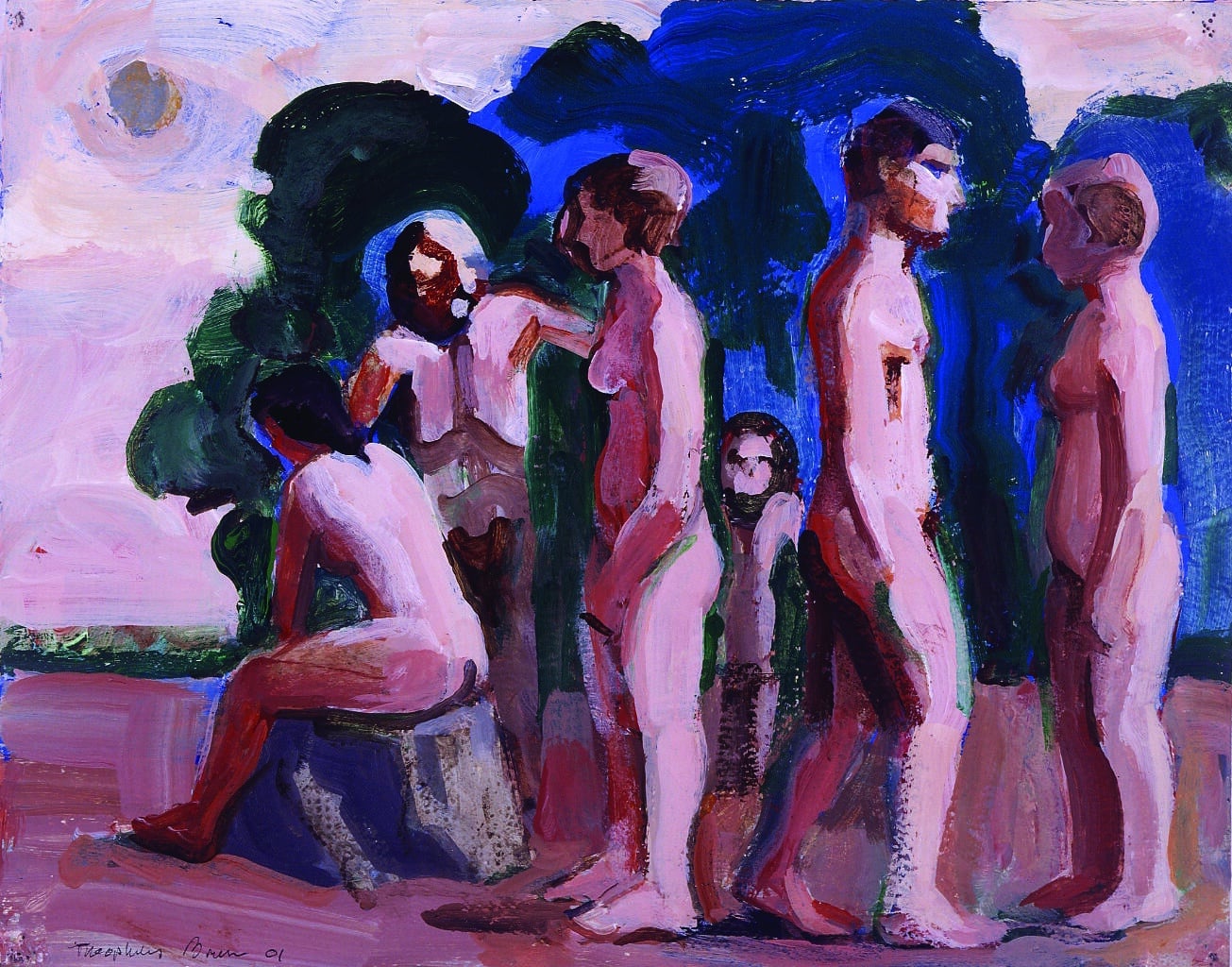

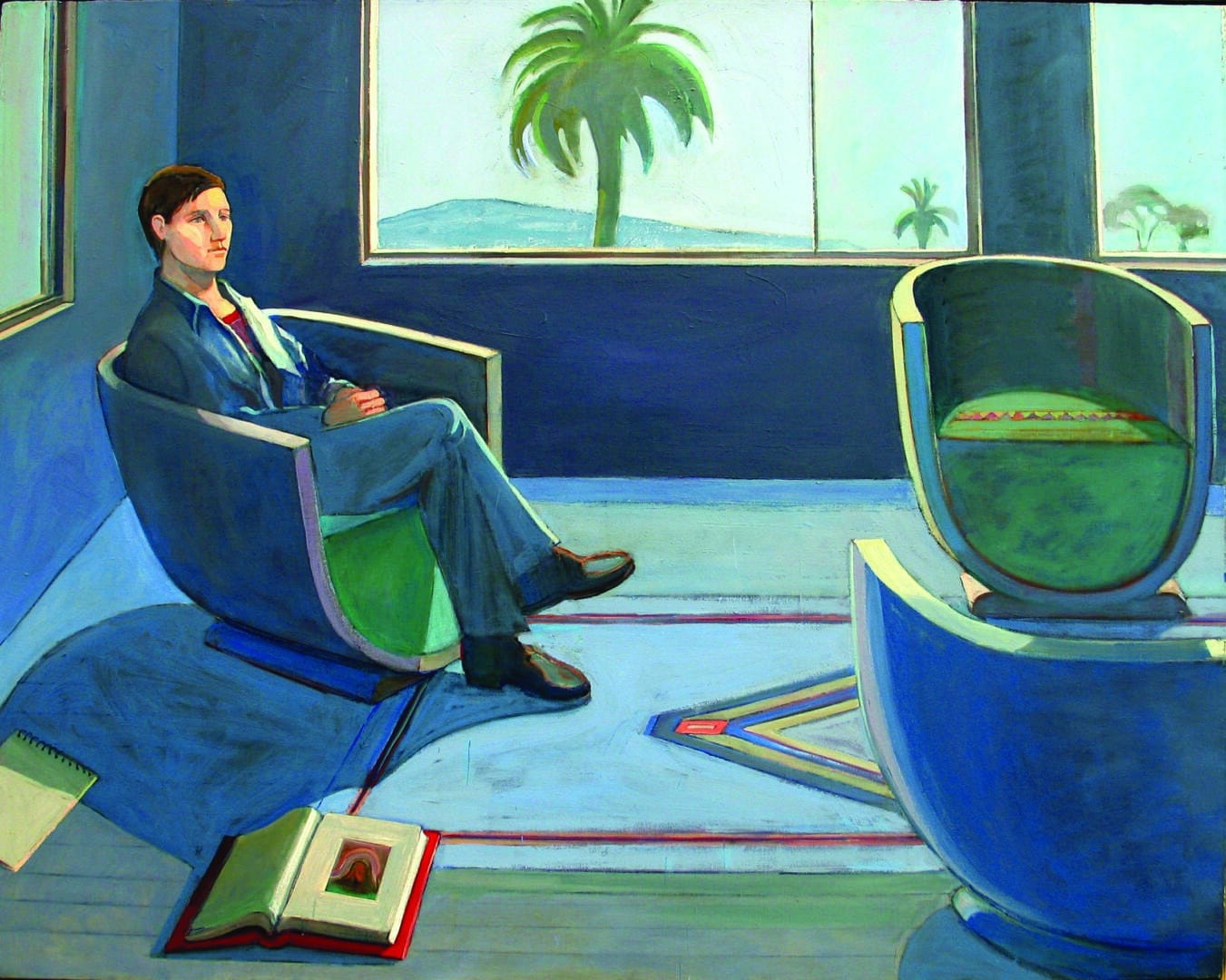

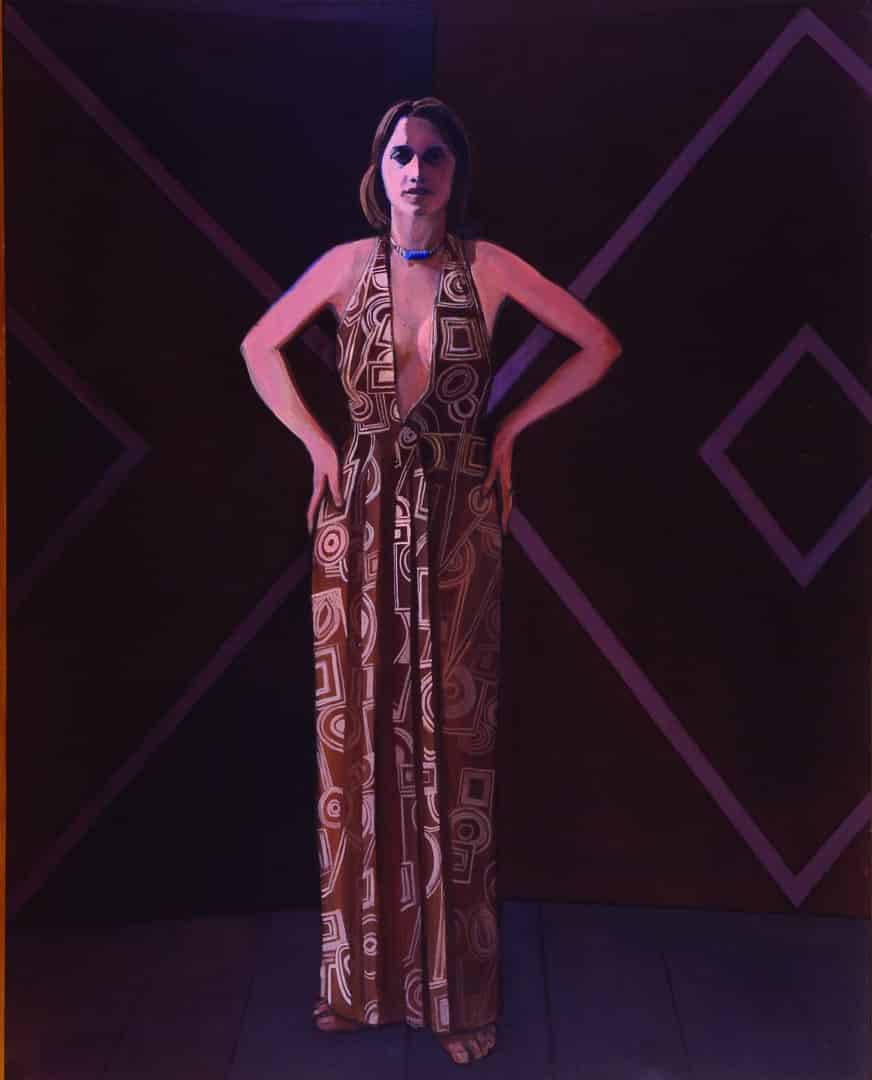

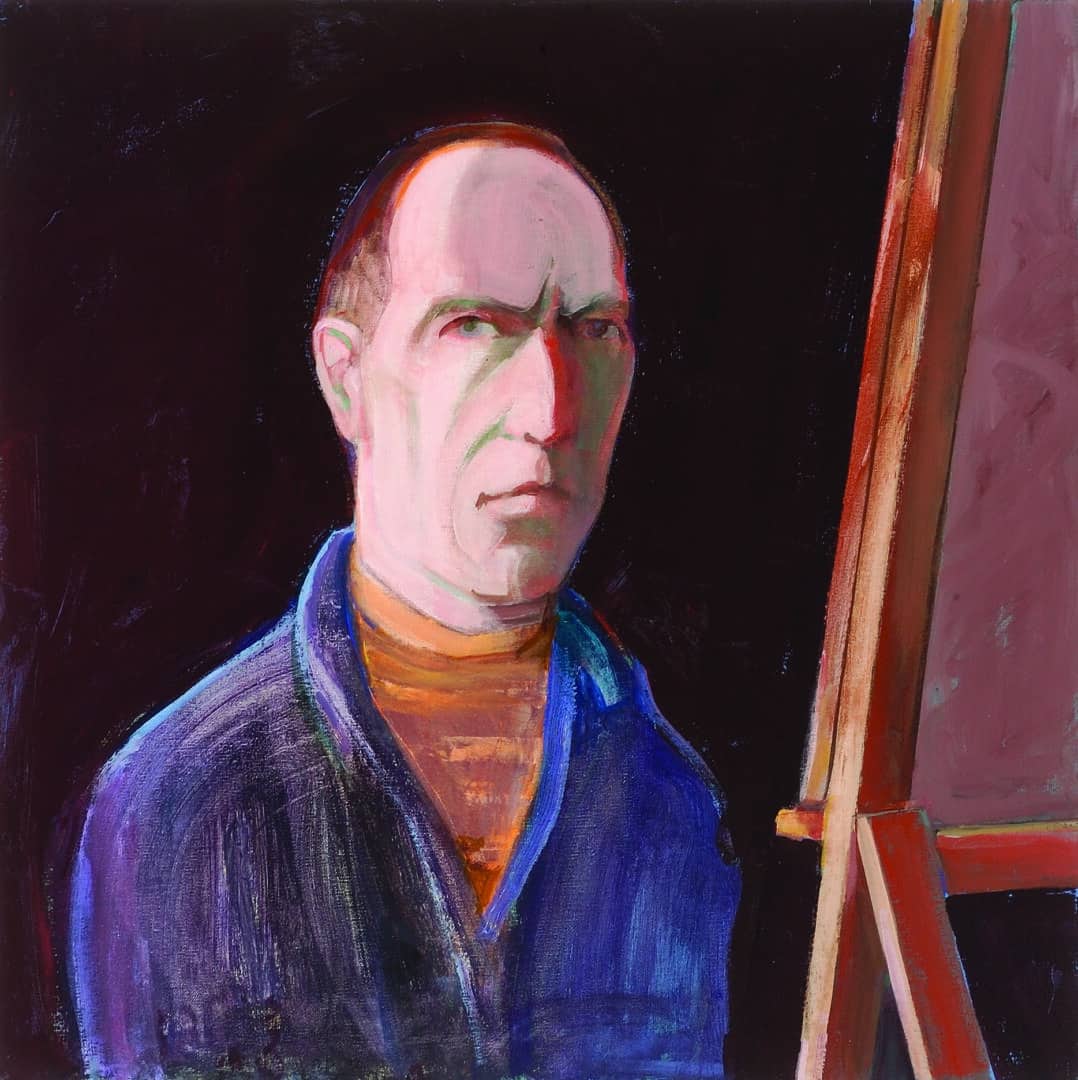

The ensuing years in Santa Monica and Malibu were productive and prolific, both personally and professionally. Brown refined his figurative work, moving toward the more representational. He painted, on canvas and on paper, an impressive number of beach scenes featuring mostly male nudes – by far his most comprehensive series. There is a voyeuristic quality to the work, as if the viewer has stumbled upon a scene of intimacy, not necessarily sexual in nature, but certainly personal. Still, there is a sustained sensuality in Brown’s work that creates a quiet sexual tension in many of his paintings, drawings and even portraits and self-portraits. While the figures are the seductive center, Brown wraps them in carefully constructed abstract landscapes, which seem the genesis for a series of urban and industrial landscapes he would complete a few years later. Painted from his own plein air sketches and photographs of factories and working docks in San Francisco, Oakland and Alameda, the subject matter is clearly recognizable, but look closer. Brown has stripped away the detail, and instead focused on shape, form and light. Devoid of life, except for a stray dog or the occasional faceless figure, these paintings have none of the sexual innuendo of his figurative work, but there is still an emotional pull. Loneliness and urban isolation permeate the paintings, leaving the viewer with a vague sense of loss.

Most of the work in the landscape series was done over a short five-year period, but Brown was never far from the figure. Throughout his career the weekly drawing sessions continued, as did portrait work. If there was not a live model available, a friend would step in, or Brown would simply use a full-length mirror.

The relationship between Wonner and Brown endured. Wonner died in 2008, leaving a void that Brown says will never be filled. “He was the central person in my life, no doubt about it. He was also my best critic, and I think I was his best critic, too. Particularly when I did something that wasn’t very good and I wanted praise and reassurance, I didn’t get it from Paul. He was always honest and I was, too. I think that’s what I miss the most. He was a marvelous man and the loss is constant. It’s still not easy to live without him.”

As Brown enters his ninth decade he still works in the studio everyday. His art has taken a decidedly different turn prompted by a serendipitous piece of peeled paint. “I scraped this piece of acrylic paint off my palette, and I thought the shape was so beautiful I saved it. I put it in a drawer, and then one day when I was stuck on a painting, I got it out and made a little collage,” he explains as he gets up to retrieve a small, no larger than 4” x 4”, piece off the wall. Since then Brown has done hundreds of these abstract collages. Many of the great painters of the Bay Area Figurative Movement – most notably Diebenkorn, Park and Bischoff – embraced the non representational later in their careers, but Brown never did… until now. He always believed he incorporated the best of abstract expressionism into his work, but now it’s overt, and he’s having a great time with it. “Diebenkorn once said I would never be an abstract painter. Well, he was wrong,” says Brown laughing. Occasionally he works on the collages with other Bay Area artists Matt Gonzalez and Gustavo Ramos Rivera. “We don’t collaborate,” Brown is quick to point out. “We just work together in the same room. I think Matt likes to have company. He is a social animal.” And truth be told, so is Theophilus Brown. Throughout his 90 years, he has nurtured lasting and profound friendships, cultivated his art and generally lived life to the fullest. “I’ve been lucky in many ways,” he says simply.