trash talking

Written by: Kiera Scholten

At a time when much of Seattle’s eco-friendly population is bringing cloth bags to the grocery store, Chris Crites is still opting for paper. Before the extreme environmentalists out there label this painter a wasteful consumer, let’s clarify that Crites recycles every day. The brown paper bags he stockpiles won’t be tossed—they will become the canvases for his creations.

Crites began using paper bags for art’s sake out of “accessibility and affordability,” but their purpose has evolved into much more. The pops of color he paints on this mundane material give new life to an otherwise disposable item. His bold, bright images jump off the warped, mangled surface.

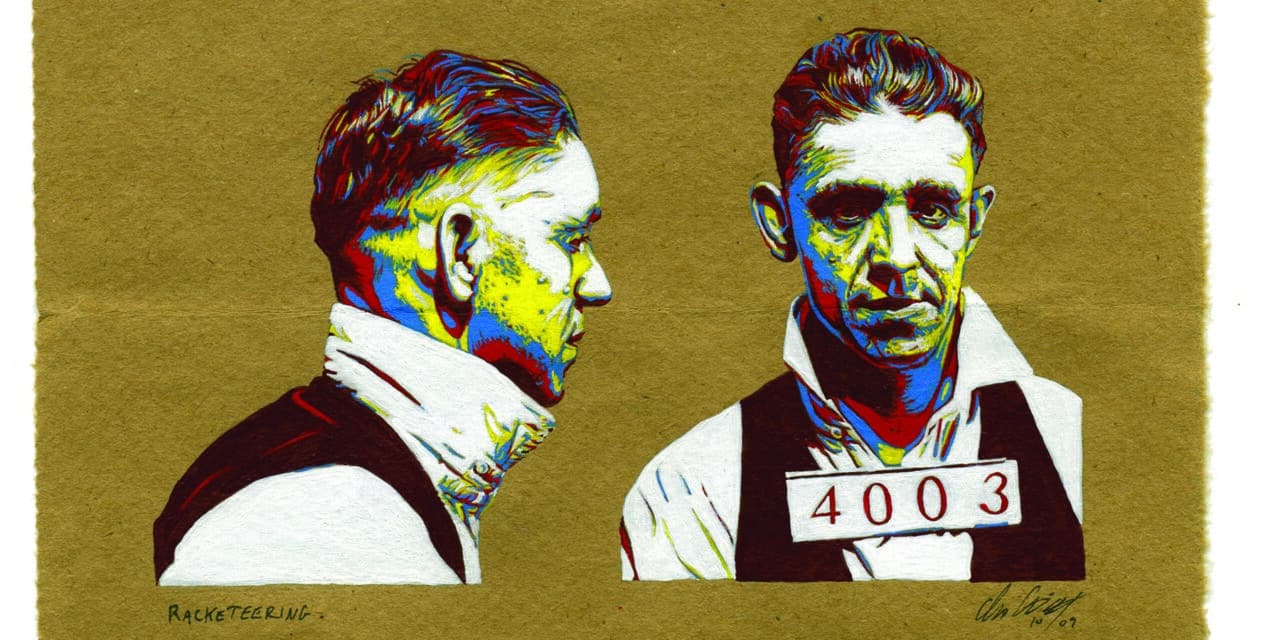

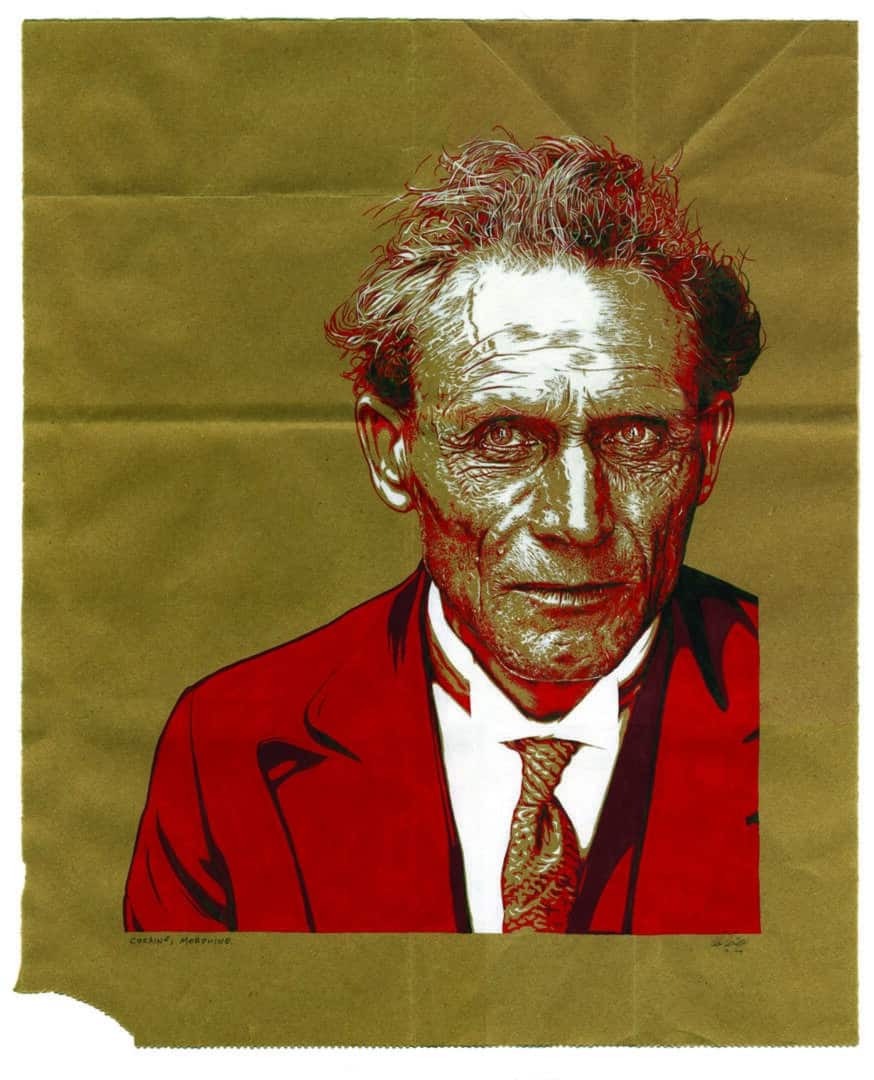

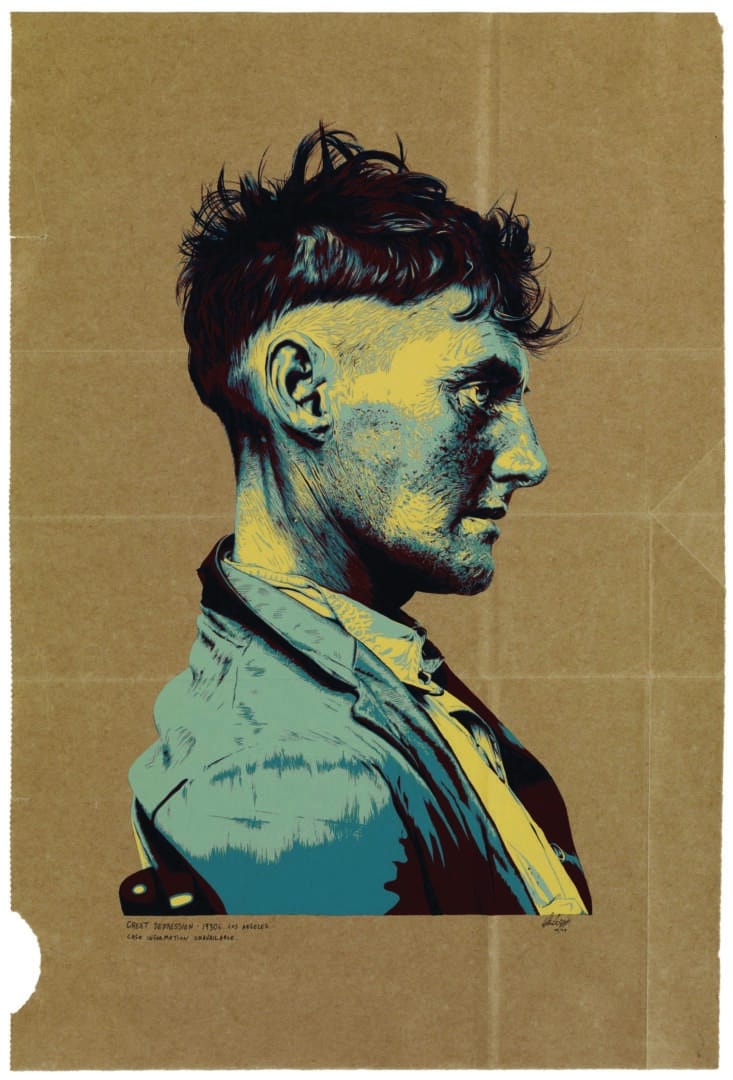

His subjects are often as worn and torn as the paper on which he paints them. Crites creates portraits of people often deemed the “trash” of society—unloved, lowly criminals. He spends hours poring over books and digging through boxes at the state archives looking at historical mug shots—forgotten images of discarded people. “I became very curious with their history. What drove these people in their lives? What were the situations that got them to the point where they ended up in front of an amateur police photographer?” He looks into the eyes of the dejected, then selects and scans the images that engage him. Crites’ creates his own vivid versions of these otherwise standard black and white headshots, with detail and color that provide a stark contrast against the wrinkled brown paper. It’s a perfect pairing. And the results are striking.

Crites spends countless hours with these people he’s never met. As he meticulously recreates the features of a fugitive’s face, he imagines what led to the moment this criminal got caught. He studies the clothes and the hair, often far too nice for a criminal, and the facial expression, which he says might be “goofy, drunk, furious, desperate, innocent, or guilty.” Sometimes the reason for the arrest is included with the mug shot (such as “kidnapping,” “bar brawl,” or “polygamy”), offering a glimpse into their back-story. But if the charge isn’t there, Crites makes it up. It’s a process that can take a lot of time, thought, and study, because he wants to be as true to the photo—and this person’s history—as possible.

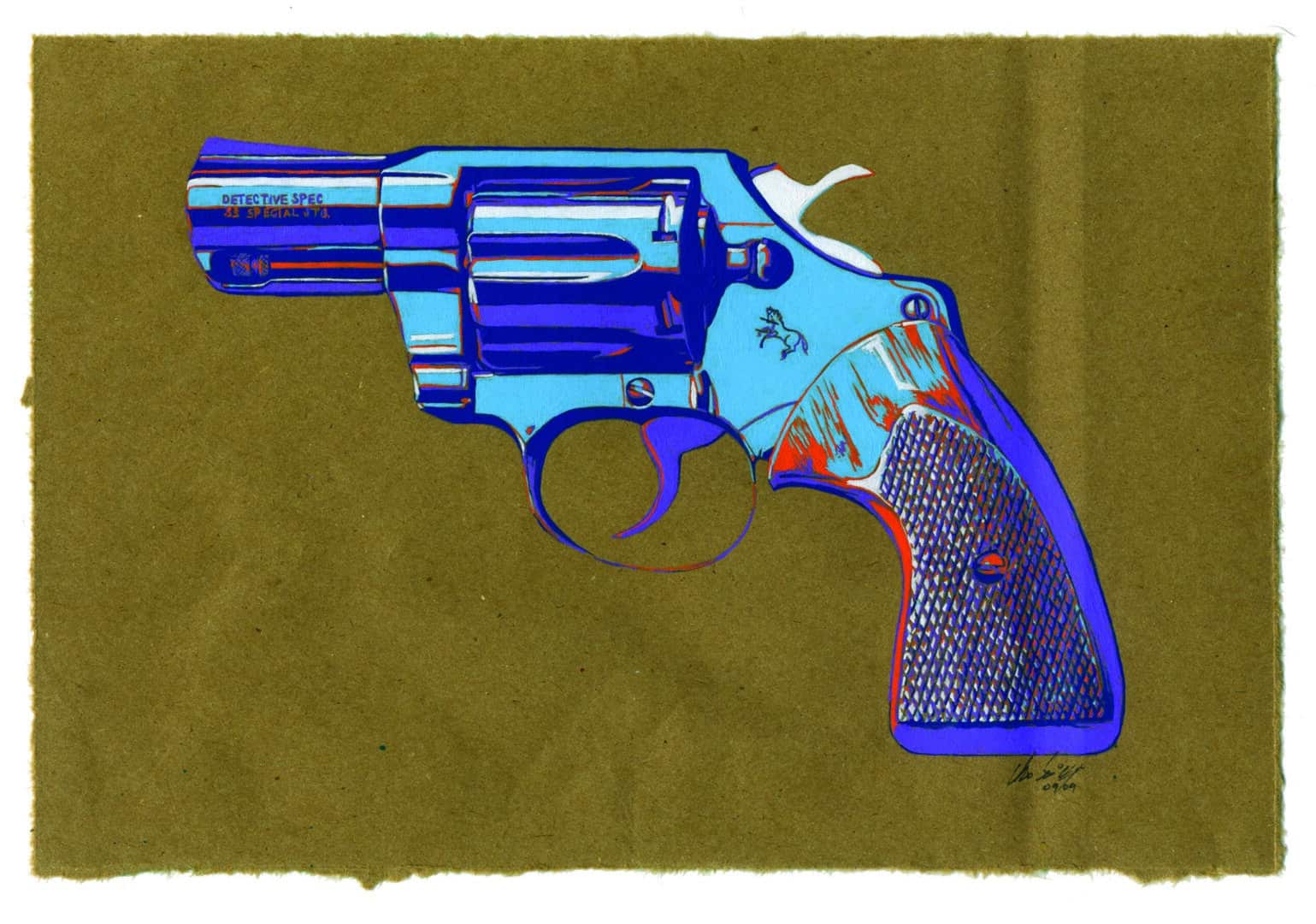

Painting characterizations of criminals consumes much of Crites’ work, but he’s dabbled in other endeavors as well. Other subjects include post-World War II nudes and pin-ups, old firearms, and mushroom clouds from the atomic bomb tests. The self-proclaimed history buff paints what he’s interested in, observing often-overlooked occasions in our history. “It’s my hope to get people thinking about the past, their present, and how we all affect both,” he says. The mushroom cloud series held a personal connection for him; his father had worked on radiation testing and his stepfather on the Manhattan Project. “The mushroom cloud is easily identifiable, it’s terrifying, and it’s fascinating at the same time—like a car crash. Why would you slow down to look at a car crash? Well, what happened?”

Crites is most drawn to these macabre moments, but he paints in bright colors that prevent any of his pieces from feeling too heavy. He says his selected subject matter might be born from his pessimistic nature. Though he claims he’s always been a worrier, it doesn’t seem to have held him back. He likely wouldn’t be a full-time artist today if he’d let negativity get in the way.

His passion for painting began as a child spending summers with his grandmother, a talented painter from whom he enjoyed watching and learning. But like many young artists, he had his share of people making sure he got his daily dose of reality. “I’d always been told, ‘Oh, you can never make it as an artist—you have to have a real job,’ so that’s what I thought for awhile,” he says.

After graduating from college at San Jose State in California, Crites began as an illustrator. It was “a way to pay the bills,” but he knew he could never be happy working under someone else’s vision. He and his wife were also unhappy where they were living. They moved from California to North Carolina to Arizona but didn’t find their fit anywhere. When they visited Seattle for a friend’s wedding a decade ago, they knew they’d found a match—and moved to the Emerald City a few months later. Seattle’s urban area, surrounded by countless opportunities to get lost in the woods, provided an abundance of avenues to feel inspired. Additionally, Crites was welcomed into an incredibly supportive art community. In 2005 he finally made the leap to being an artist full-time. He wouldn’t go back. “If I wasn’t an artist, I’d probably be an archaeologist,” he says, remembering the only other career that had captured his interest as a child. Looks like Chris Crites got two dream jobs in one—he’s still digging up the past.

Today if he’s not searching state archives, working at his home studio, or curating at local galleries, he’s possibly planning the perfect crime for his own mug shot. “There are plenty of crimes I could just go out and do, but it would have to be true to me. I don’t know what that would be. So there’s this debate, do I go out and get arrested and do a real mug shot, or do I just make one up?” he wonders. We likely won’t see a self-portrait from Crites anytime soon, since it would go against his nature to fake it (and I don’t think he’s a criminal). He seeks truth in his work, uncovering uncomfortable moments from our collective past, with the hope that these glimpses will get us thinking about our future. One thing’s certain—Crites makes sure the forgotten faces don’t go out with the trash. It’s in the bag.