Cecilia Miguez

written by: ben bamsey

Curious objects are everywhere. Bins of antique clock faces. Bags of strange gears. Boxes stuffed with random metal parts. Little jars full of lost trinkets. Big shelves stocked with evocative slabs of wood. Racks overstuffed with rusty tools and saws. A workbench with blobs of delicate, partially shaped clay and elongated sets of bronze extremities scattered on it. And in the center of everything… a spirited, yet humble woman with worn hands – a matchmaker of material things who melds traditional methods of sculpture seamlessly with Medieval-like craftsmanship. When found marries new in a Cecilia Miguez sculpture, time is given extra sand, dusty stories are given relevance again and the realm of possibility bloats a bit more.

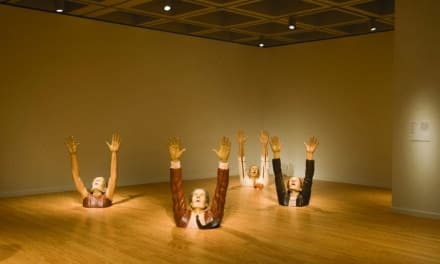

Every day Miguez gets up early and makes the long drive from her home in Santa Monica to the studio space she shares in Altadena. Inside the converted garage her muted friends wait anxiously for her hands to feed their spirit. Their heads, arms and legs are all molded from warm wax and then bronzed. No models. Just feel. Unique personalities are massaged into each face. Eyes become open gates to deep souls. Their transplanted bodies have already seen the realities of the world. They are full of interesting scars that give them heartbeats. Each emotionally provocative series takes two years for Miguez to craft. The completed works are full of purpose and meanings. Old objects maintain their life while a fresh and sublime connection is naturally fused between them.

“The found object is something that somebody made with another purpose,” Miguez says with a soft-spoken Spanish accent. “I really like old pieces. It’s very special when I hold some of those objects and I think about somebody else working with them. All these pieces are full of purpose. For me they are canvases; great places to start. They give off incredible vibrations to the work.” Miguez’s latest exhibition is a study of the seasons. Through material, construction and artistic vision, they tell the story of the changing winds. In Spring, the body is built from a four-foot tall, antique Japanese instrument. “When I first saw the instrument,” Migues recalls, “I immediately saw a woman with a beautiful face and shape. Like the wood, she was so fragile.” The strings had long since been missing, but there’s a lasting imprint of music tattooed on the piece as ruts and grooves streak across the neck. Decorative buttons adorn all the string holes except one where Miguez chose to attach a metal bumblebee, instead. She carved two sections of wood to make the body more cylindrical, but kept the piece hollow like the instrument itself. Miguez also made a golden bird that she had intended to perch on a gap between the wood sections, but it accidentally fell inside the body of the sculpture. So she left it there in that open space. The shoulders, arms, hands and head are bronze with an elegant white patina. The female figure is hairless, flexible and free.

Winter tells a different tale. The body is rigid, made from richly colored blocks of solid wood. Iron rings divide it in four sections. Rounded metal notches serve as a kind of armored protection. A wooden Chinese pillow restricts the figure’s dark bronze head. The position of her arms is tense, and her feet locked together. The metal that hangs down from the neck looks like two long cowbells, but they’re actually forms of currency in some cultures with size determining value. The symbolism is clear: winter is a time to assess the year gone by and to determine one’s level of contentment. The flip of the calendar can’t come soon enough.

Movement is an integral component of Miguez’s work, both in form and function. Take the Embroidery Lesson, for example… the body is nothing but little drawers, dozens of them that can be opened but not pulled all the way out. The headpiece has a shovel behind it and a golden needle and thread attached in front. The sculpture was built in a series of plates, all of which spin. This is a piece of art that makes quite a statement about the value of hard work. In Time Keeper, six ancient Hungarian clocks are attached to the cube-shaped chest. The back of the sculpture can be opened, and each clock can be wound or set. The bronze figure is wearing a ridiculous Latino clown suit. A bell hangs from a string attached to an enormous hat on her head keeping a monkey next to her occupied. The figure is a cross between a jester, magician and circus performer – one that asks us to laugh at life’s little treasures while mocking the time limits that control our mortality. “To me all these parts symbolize certain periods of a life,” Miguez says. “We are formed by our own varied experiences. Same thing with the art – there are so many contrasts in the texture, but then the whole piece has to relax so you don’t see the differences in the objects. Basically, everything has to work with the other, but not too much.”

Another staple to a Cecilia Miguez piece is its worldliness. She scavenges flea markets and antique shops around the globe looking for objects, shapes and material that have been places, not simply taken up space. She’s well traveled herself. She first learned how to paint the figure from private teachers in Montevideo, Uruguay, before moving to Los Angeles with her husband and discovering art’s third dimension. As her work in sculpture evolved, she began purposely leaving out personal anecdotes. It allowed the figures to mature on their own, and gave them a universal appeal. Devoid of a mandated story, their plights become more compelling because we can attach our journey to theirs.

There is, however, one piece that’s incredibly personal to the artist. She named the sculpture Penelope, after the faithful wife of Odysseus in Homer’s Odyssey. Her beauty was in character and conduct as she warded off her suitors before being reunited with her long lost husband. Miguez’s personal life headed down a similar road, and through the symbols in her art she asked her husband to re-marry her. The base of the Miguez sculpture is massive. The legs seem way too big for the torso. The subject clearly shrinks as it ascends. The hips are two inches smaller than the thighs leading to an immobile midsection. But then there’s a delicate openness to the exposed and significantly smaller shoulders, neck and face. Fragile fingers hold oversized knitting needles above the waist. By mass alone, the biggest things are the base – the legs you stand on – and the very large tool in her hands. A marriage must be built on a strong foundation, but even then it takes hard work to sustain. Vulnerability is one of the sweetest elements of the human condition. Love seems to draw it out the most. Miguez’s soft gesture created the energy to win her husband back.

Cecilia Miguez is ruthless with a saw and hammer. She is a meticulous engineer of ideas, one whose craftiness ensures that her creativity goes without limit. As a result, her art is fantastic and mystical, nostalgic and surreal. But her most impressive gift is her tenderness. There is a true thoughtfulness that goes into the artistic statements being made – for Miguez believes her sculptures deserve to have the voice. And thanks to the harmony between old and new material, emotion oozes from the work giving it the power to stand and speak for itself.