wood you believe me

written by kiera scholten

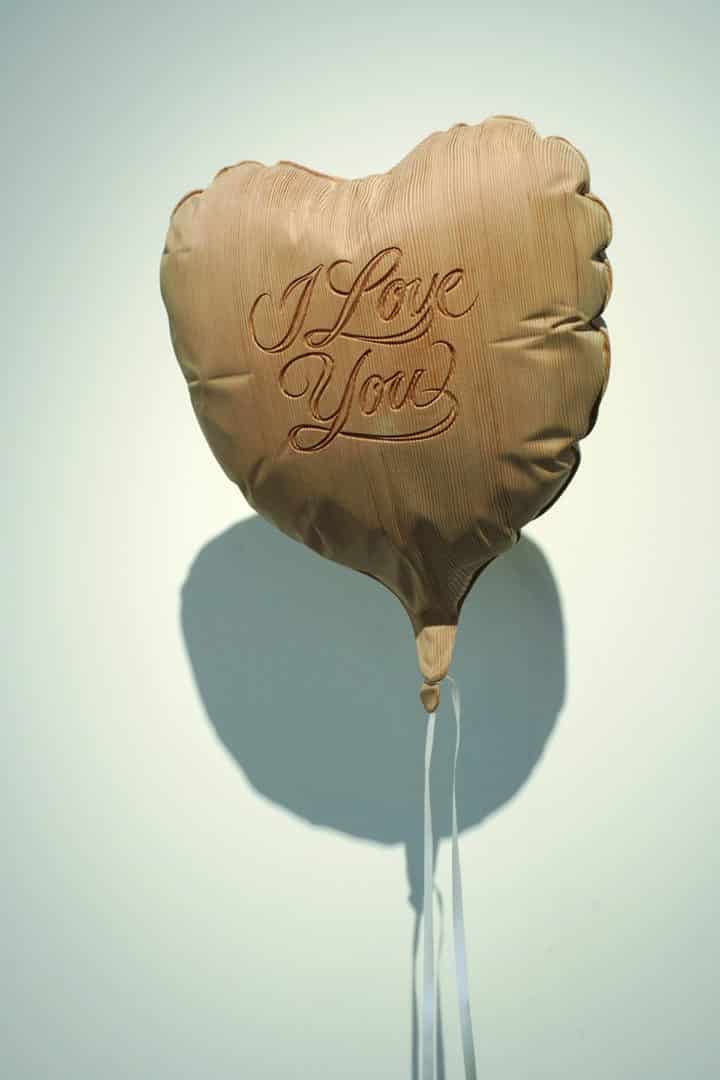

A dandelion that never dies always awaits a child to blow it into the breeze. A mylar Valentine’s Day balloon that never loses air mirrors a love that never fades. A candle with an everlasting wick never loses its flickering flame even in the most powerful wind. A childhood embrace that never ends shows the power of true friendship. A tray of food that never rots will always feed one’s hunger. Dan Webb freezes these otherwise ephemeral moments in wood, marble, and metal, among other materials—to confer lasting value onto what otherwise might not be valued at all.

The Seattle-based carver considers his craft a way to share common experiences that connect all of humanity. His last name couldn’t be more appropriate, because Dan Webb weaves a web of connections through his carvings. “The stories are all the same. You’re a kid and that’s magical. And you fall in love, and that’s sometimes good and sometimes doesn’t work out. You have kids and that’s great. But I think the important thing is to tell our versions of these common stories over and over and over again,” Webb says.

Webb recognizes that these stories can be told many ways, but he chooses to tell them through his art. Spending much of his childhood in Alaska could have fueled his creative interest. His family moved to a remote village on an island in the Bering Sea the year before television arrived. It was here that he realized the importance of music, storytelling, and craft to our human history. “These things were all primary activities, above and beyond surviving,” he recalls. It pains him now to see how far removed our society has come from this mindset, with most people now considering these activities a “frill” reserved for leisure.

From a young age, Webb enjoyed making things and says he always assumed he’d be an artist. It took him awhile, though, before he realized he could actually do it as his job. He assumed an artist had to be like Michelangelo to make any money. His world changed on a typical day in high school when he skipped class. Of all the places he could have gone while ditching, he ended up in the library. Flipping through an art book, he happened upon a page with a photo of a Robert Rauschenberg sculpture comprised of a stuffed goat, a tire, paint, and other odds and ends. “I thought it was hilarious. Who does this crazy stuff? But then I realized it was someone who was alive, still creating,” Webb recalls. That’s when he realized art offered the freedom he likely craved as he skipped out on class that day—and he was hooked. “The art world is intoxicating, because you can really do whatever you want. How great is that?” Webb marvels.

Following high school, Webb transplanted himself from Alaska to San Francisco to attend art school. He says it “didn’t work out” and he dropped out. Instead, he started learning the craft of carpentry to pay the bills. It was probably a serendipitous choice, as it provided the foundation for a future in carving

Webb spent years as a carpenter while still considering himself a carver first and foremost. So eventually he took another stab at art school, attending Seattle’s Cornish College of the Arts and faring much better than the first time around. He graduated magna cum laude. While he loved carving, conquering the craft seemed like an impossible task; he considered the learning curve too steep to ever master it. A professor helped him get his feet wet, and he’s been mastering it ever since—though he admits he’s far from an expert. “Maybe when I’m an old, broken-down dude with gray hair and my teeth falling out, I’ll be able to claim that,” he says.

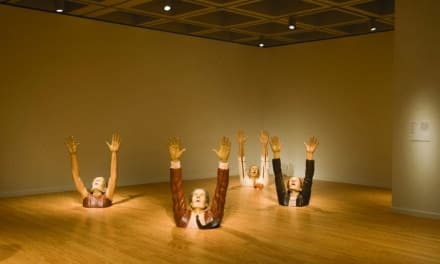

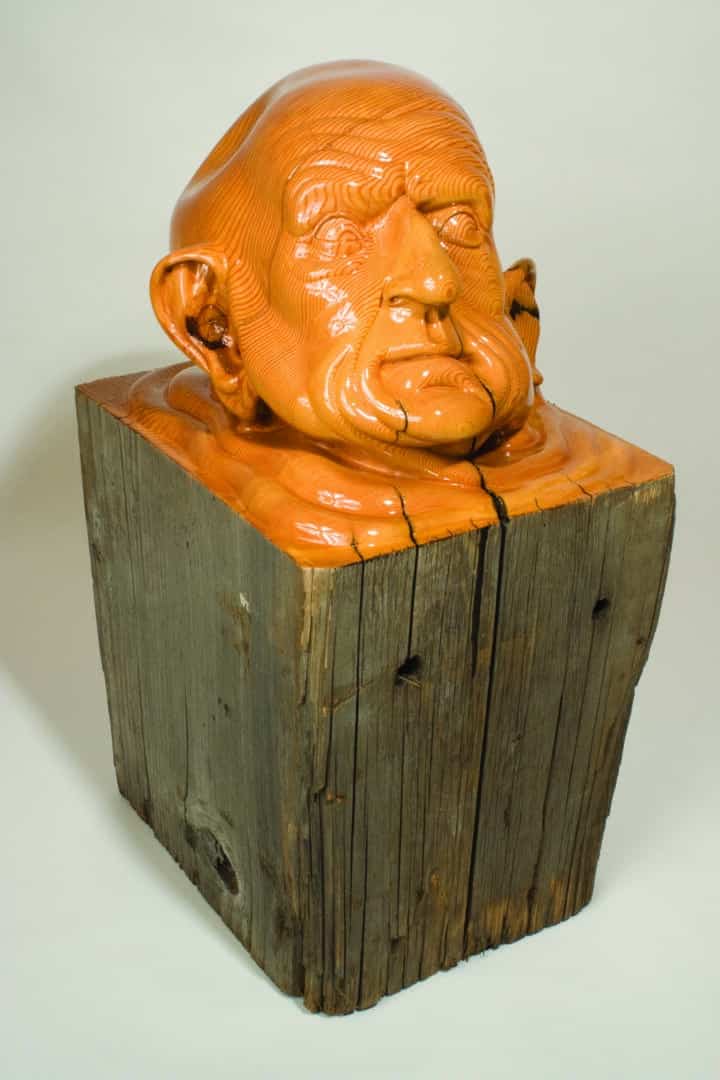

But Webb is no novice. His sculptures stop people in their tracks, asking them to steal a second glance. He transforms a block of wood into something with a surface so smooth it begs to be touched, and you can do just that without getting a splinter. His “Shroud,” which is in the collection at Seattle Art Museum, triggers double takes from passersby who likely assume the piece is fabric. With the realistic representations of water ripples in “Drop,” viewers might think there’s a leak in the roof on a rainy Seattle day.

These pieces require a closer look to appreciate the craftsmanship Webb wields with his carving tools. “I always tell people carving is super bloody simple because you just have one choice. One. Are you going to take off more, or not?” Webb never takes off too much—or too little, for that matter. His work is painstakingly carved to perfection, yet unpretentious.

As viewers get close enough to see the grain in the wood, Webb wants them to go further. It’s not enough if people are simply infatuated with the skill they see employed before them—he wants to show something to their minds and hearts. There’s more to be uncovered here. There’s a head underneath that shroud that we’ll never see. There are two figures underneath that blanket that could be sharing secrets we’ll never know.

One can analyze and interpret to exhaustion with Webb’s work, and that’s the way he likes it. Certainly experiences in his own life inform his artistic decisions—birth, death, love, loss, isolation—but he doesn’t want his story to be what people think about. “The last thing I would want to do is feel melodramatic about any of that stuff,” Webb says. “My job is not to tell my story; it’s for you to be able to connect to your story. Realizing I have one too is fine, as long as you realize that we’re all telling a version of the same one.”

Webb has his feet firmly planted in this century, but his awareness of the past is just as powerful. His work is at once modern and timeless; it’s current, with an undeniable historic connection. The fact that his material is something with its own long history only gives each piece more treasure to unearth. What once might have been a towering tree on a Northwest hillside may have lost its life to a lumberyard before it ended up in Webb’s studio. “One of the reasons I’m a carver is because I live here—there are huge pieces of wood I can use just lying around.” These discarded materials get new life under Webb’s watch. He revives the past with the hope that we’ll pay attention.