no title

written by ben bamsey

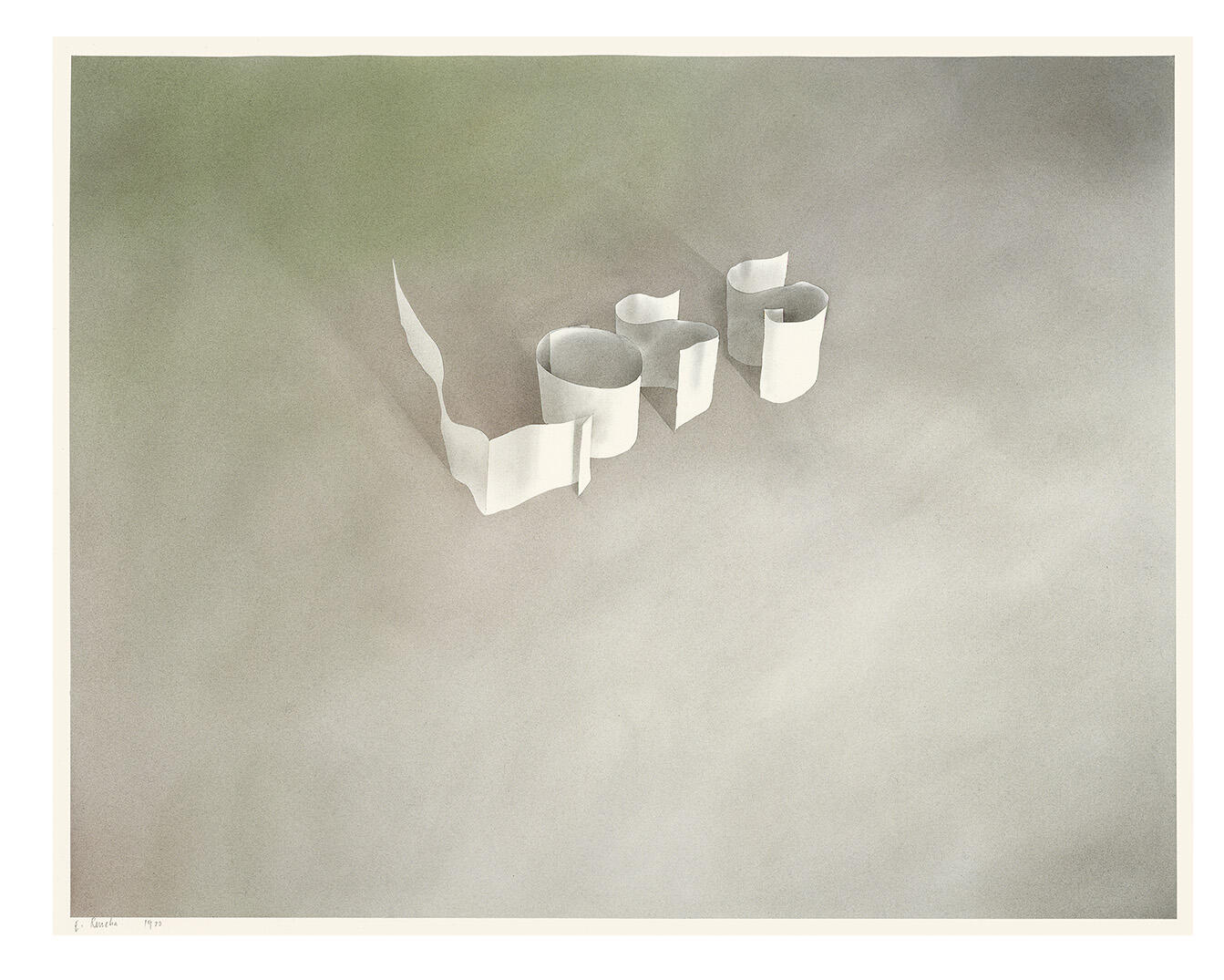

Welcome to the creatively bizarre world of Ed Ruscha where art is something designed to make you scratch your head. It doesn’t need to make sense; it just needs to make you stop and look. Like his sense of humor, Ruscha’s work is sly and somewhat elusive. It’s not complicated; it’s just so different that you can never quite put your finger on it. He’s spent the last fifty years testing boundaries, shifting mediums and materials and constantly reinventing himself. He’s a painter, photographer, printmaker, bookmaker and filmmaker who can’t be pigeonholed into any one style or sensibility. Ed takes it all on, never playing by the rules. His talent is the reason he’s on top of the game.

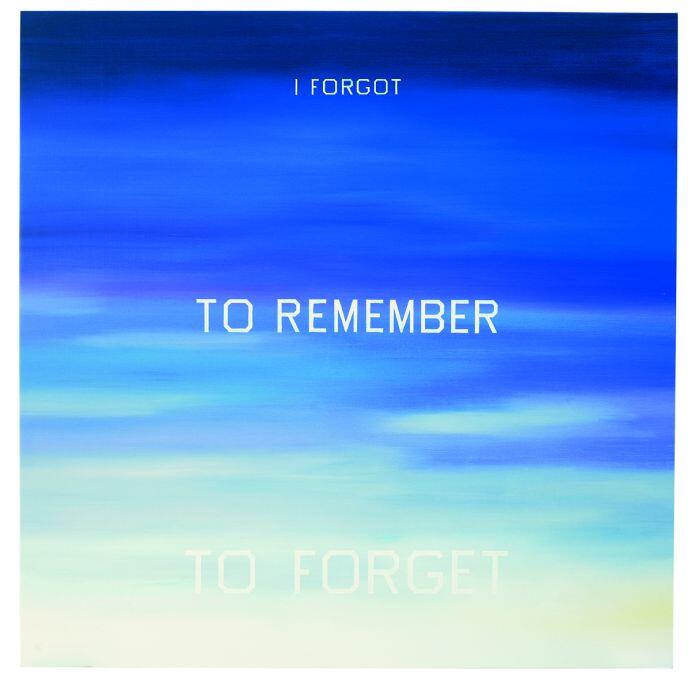

“Making art is like an involuntary reflex,” Ruscha says. It’s so second nature to him that it seems he’s always a step ahead. Ed wears that quirky kind of defiance in the form of a wry smile on the corners of his face. You can almost see the wheels that are constantly spinning upstairs. He’s a slick and conscious communicator who chooses words carefully. That’s why it’s interesting to listen to him talk about his art. His pieces sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars, yet whether it’s a print, photograph or painting… to him everything is a “picture.” Ruscha says, “The word picture has an automatic quaintness that I like. Abstract painters would also use that word. Rothko, de Kooning and Kline would say, ‘Well I’m working on a picture.’ I like that. It’s not just a painting; it’s a picture.”

His mixture of modesty and smoothness is echoed by the uniqueness of his name. Edward seems to symbolize his good Midwestern roots, but with a last name like Roo-shay, he certainly belongs in L.A. He definitely looks the part: full head of hair, a good tan, easygoing attitude – at 69 years old, Ed Ruscha is a fountain of youth. His style is cultured, civilized, and fashionably plain. His massive record collection includes real country & western, 1950’s rhythm & blues and jazz… with a twist of Captain Beefheart, Frank Zappa and Tom Waits. A well-traveled man, Ed can speak first-hand about the lights of London and romance of Italy, but you can tell California is his real cup of coffee. He makes his home in the Coldwater Canyon area of Los Angeles and has a place in the Mojave Desert where he can escape. He works in Venice and people down the block call him “the king.” At the marvelously trendy eQuator Books on Abbot Kinney Street you can buy an Ed Ruscha souvenir brochure from Greece’s national museum for five bucks. There’s a whole box of them. “Ed gave ‘em to us,” the manager says.

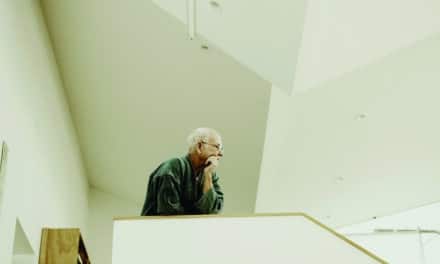

Ruscha’s studio is full of character. It’s huge and used to be a beer warehouse. Two electric gates shield it from traffic. A massive steel door and call button keep this baby as secure as the Louvre. Inside, it’s not a museum but it’s full of valuable history. Familiar pieces from Ed’s career hang in no particular order on white, modern walls. Big, old studio lights shine down from above. Stuff is everywhere, but unlike most artists, it all looks organized. Rolls and rolls of tape are stacked neatly on shelves. “I use tape for every conceivable purpose,” Ruscha explains. “You can never have enough tape.” Measuring and cutting tools and old-school film cameras are lying around. There are no easels. Tubes of paint are nowhere to be found; just two colors poured into medium-sized Diet Pepsi cups with a couple brushes sticking out. Ruscha likes to be alone in here, no music, where he can get lost in the giant expanse of his studio and creative mind.

Ed spent his childhood in the Bible-belt staring at the waving wheat and red dirt. He was born in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1937, but his family moved to Oklahoma City when he was four. Ed watched the psyche of middle-America change drastically during his youth. “There was some kind of odd success after WWII. People would leave their garden hoses running. About the time air conditioners were created in cars, people would roll the windows down and leave the air conditioners running. It was a strange kind of affluence.” Early on it became clear that Ed was an artist at heart. He made murals for his grammar school class, took painting classes in 6th and 7th grades and could draw Felix the Cat, Bugs Bunny and all kinds of cartoon characters. Ed’s parents were supportive; he went to mass and even had a paper route. “I guess I learned good four-square thinking and basic human values in Oklahoma,” Ed says. But a visit to California as a teenager gave him the itch for something bigger, and as soon as he got a car, it was all over. With high school in the rearview mirror, it was full speed ahead to the West Coast.

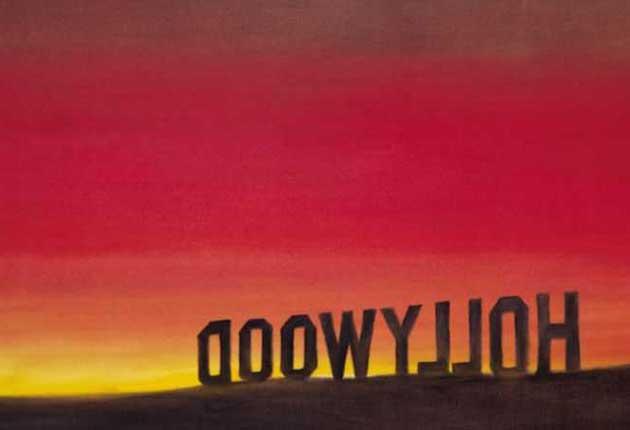

Hollywood was advanced, experimental and fashionable, and Ed liked it all. He enrolled at Chouinard Art Institute in 1956 initially taking commercial art and animation classes, a path that most often led to a job at Disney. But Ed developed other artistic interests and simply went with the flow. At first, he wanted to be a sign painter. Then, he got into advertising, book design, and even laid out Artforum Magazine for a couple years. To make some extra cash he took a job personalizing thousands of Christmas trinkets for a gift store. All these technical skills helped form the foundation of his career and certainly explain his obsession with tape. In college, Ed moved on to courses in painting, drawing and watercolor. His professors believed the spontaneity of de Kooning, Pollack and abstract expressionism equaled modern art. Ed listened but felt something else inside his soul. The epiphany came one day in an image the size of a postage stamp.

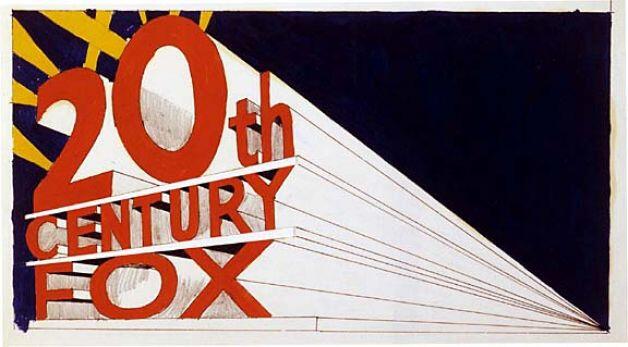

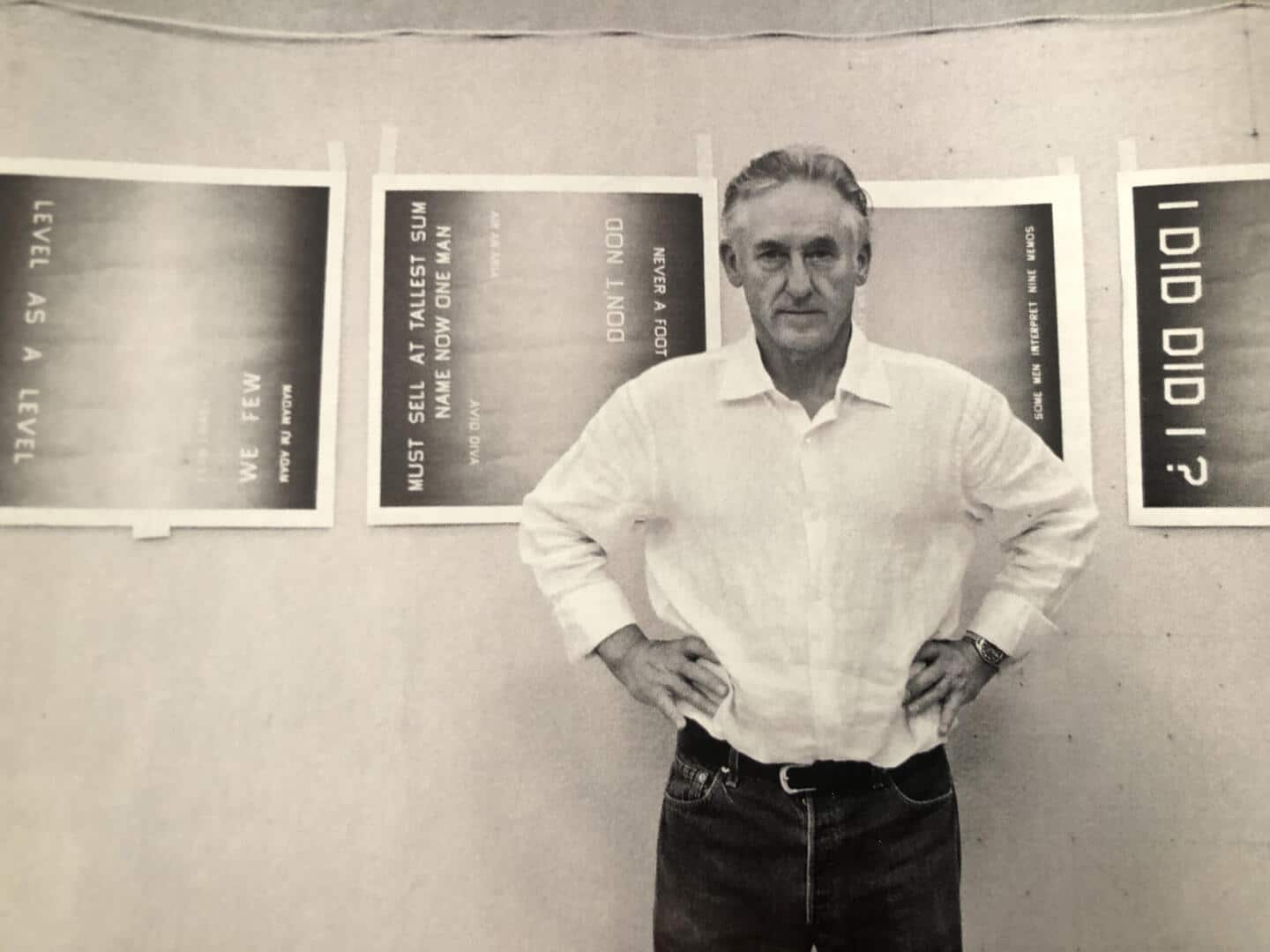

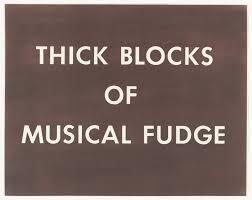

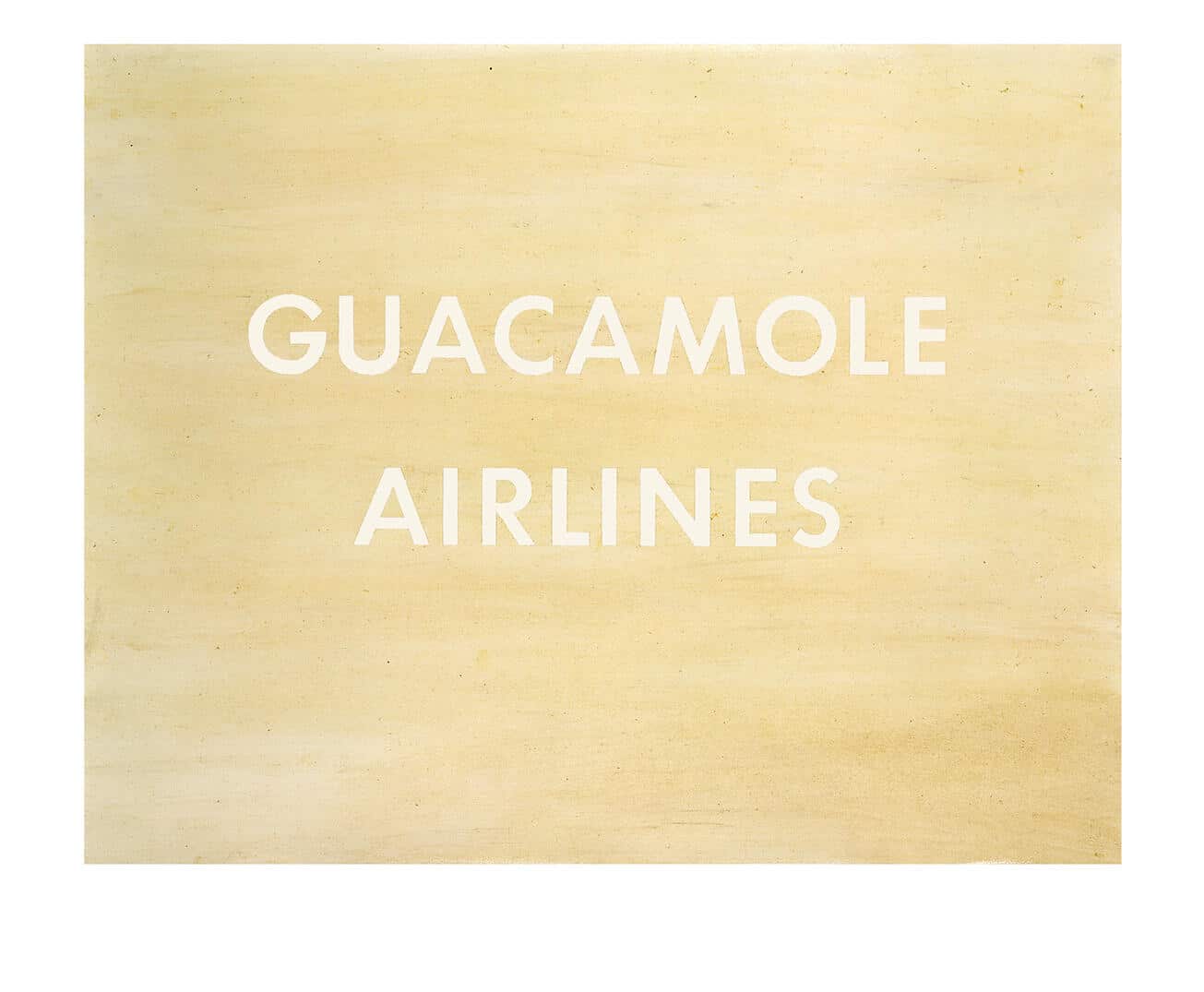

Ruscha was thumbing through the pages of a magazine when he saw a tiny reprint of Jasper Johns’ Target with Four Faces. The painting was premeditated and symmetrical and Ed was floored. “It just went counter to everything that people were talking about in school. It was not just a target. It had faces. It was something immediately recognizable coupled together with something that was totally mysterious.” Robert Rauschenberg’s “combine paintings” gave Ed that same kind of hope. “I began to see that there were some artists who were doing something that perplexed me and moved me towards a career in fine art.” With a newfound purpose, Ruscha began sticking fabric and parts of comic strips on his canvases. He also began experimenting with words and painting common objects like pencils and school supplies. The representational shift quickly turned to popular subject matter, and Ruscha soon found himself riding the initial wave of American pop art.

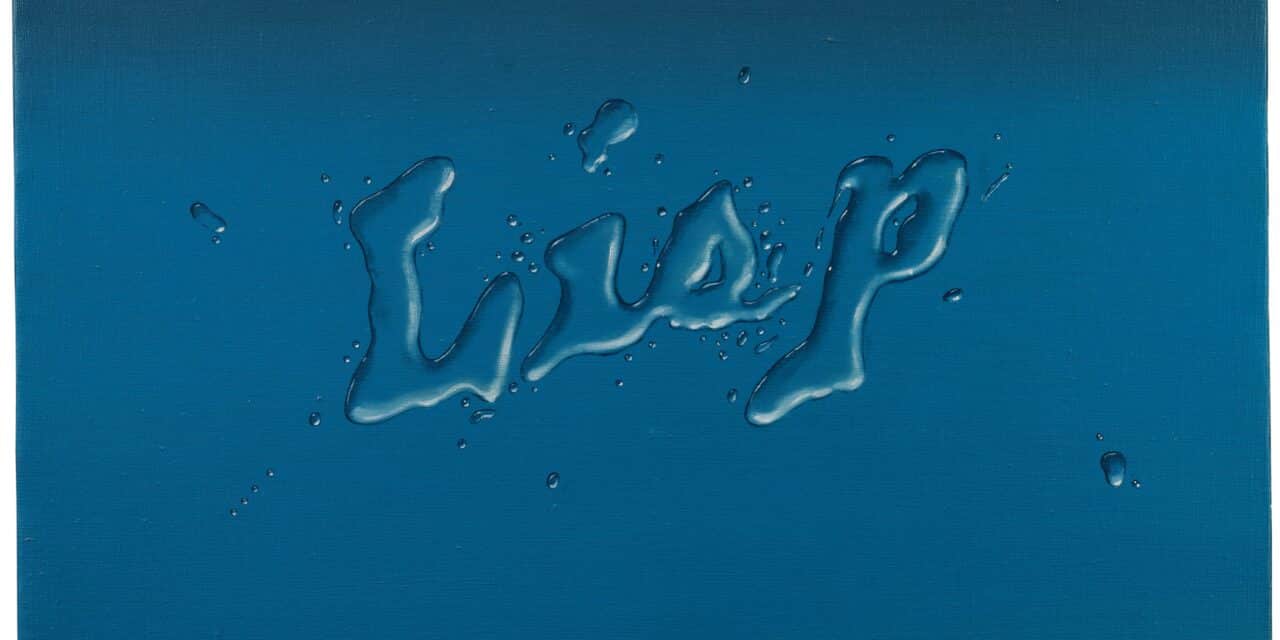

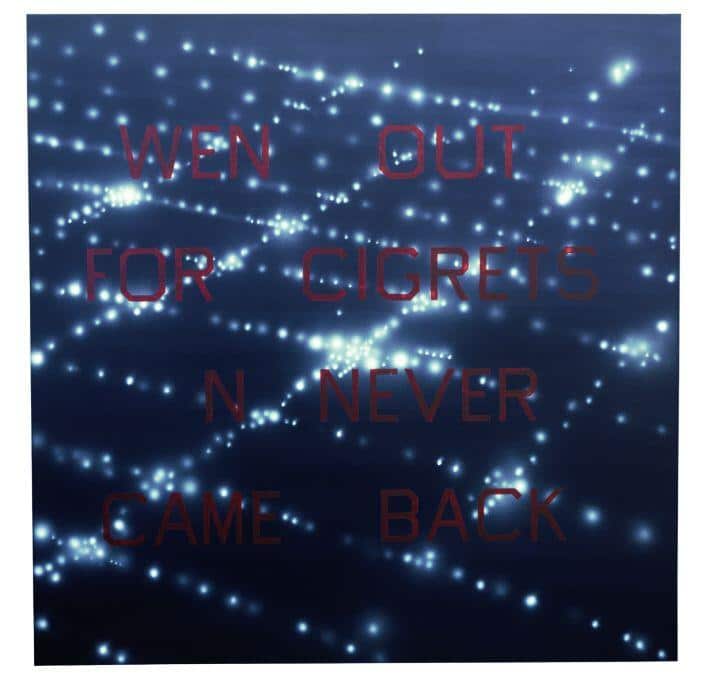

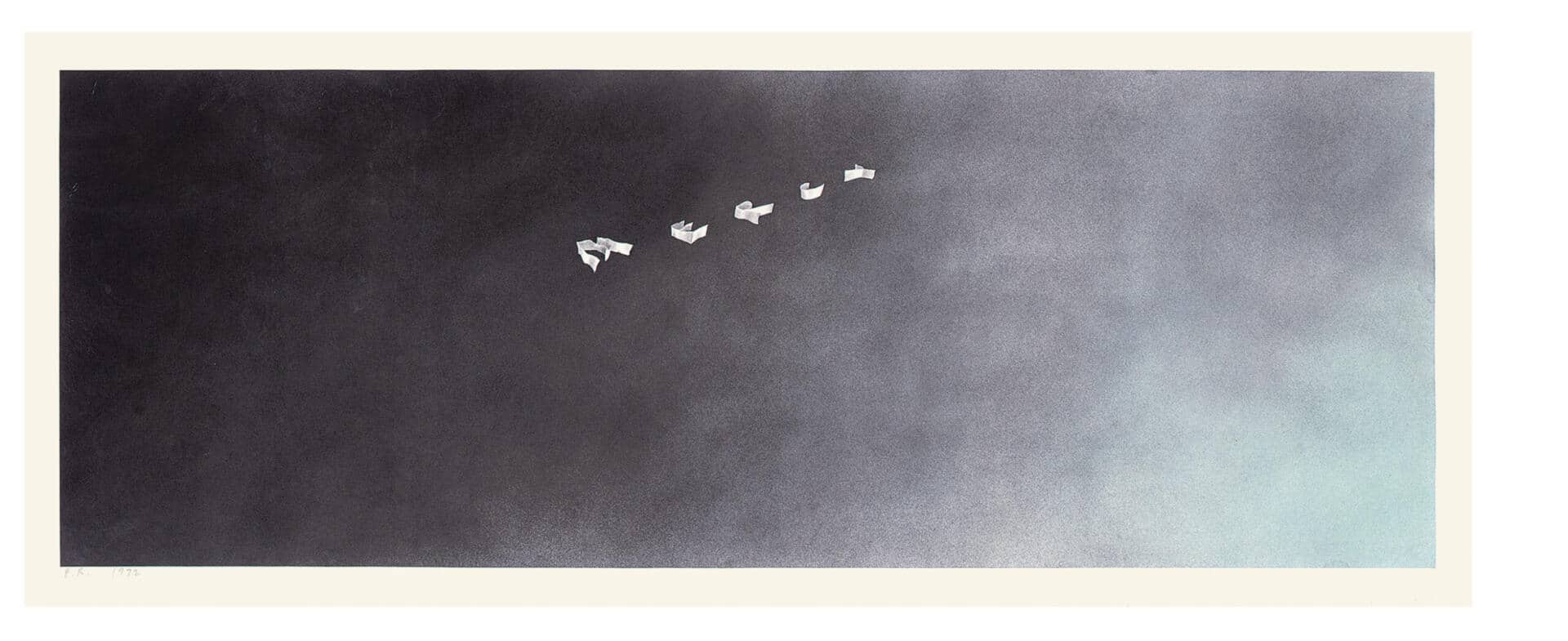

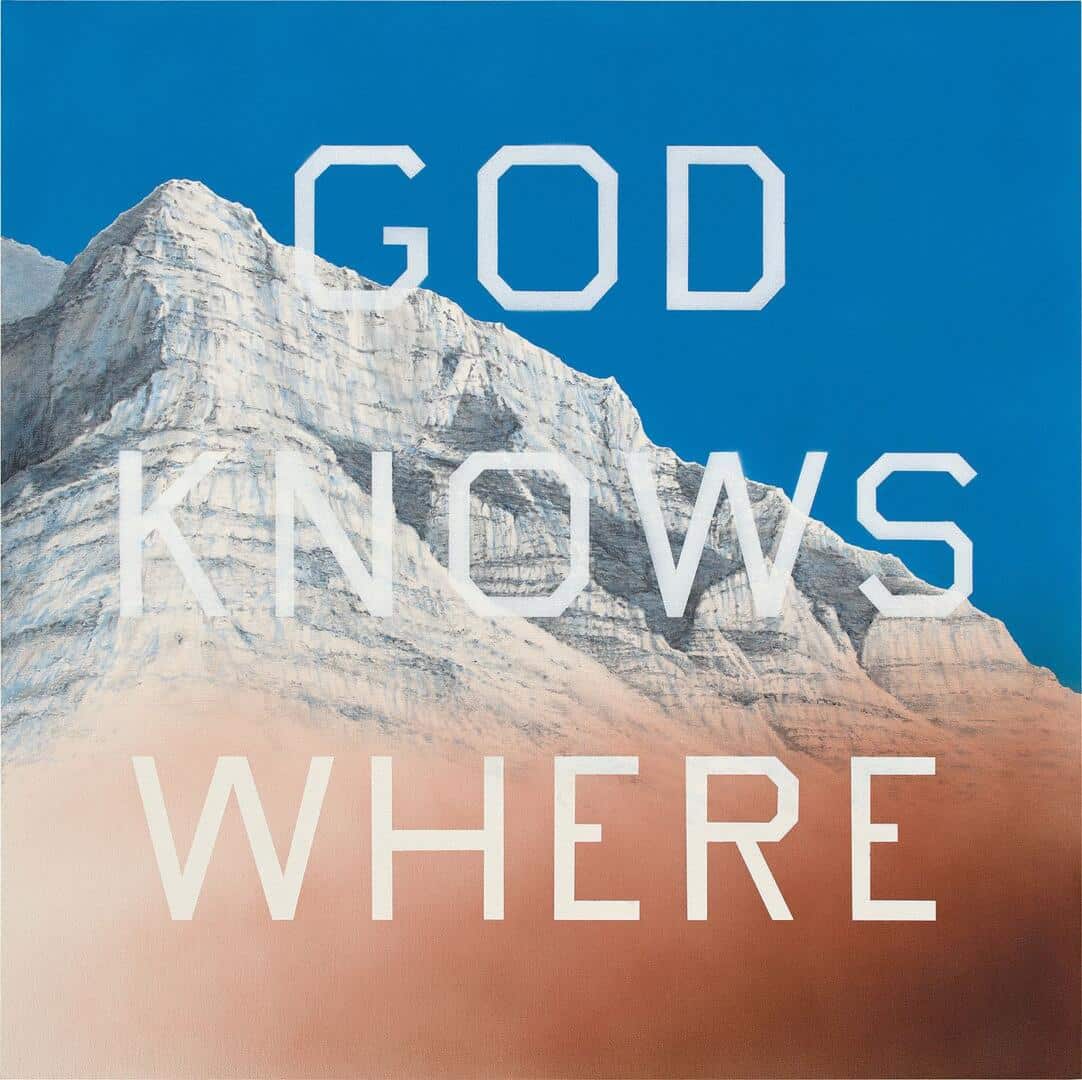

In his quest to make the work as deep as the message, Ed spent several years experimenting with stains. He smeared rose petals and spinach around words like Satin and A BLVD. CALLED SUNSET. He turned everything from coffee, squid ink, crushed baked beans and vials of his own blood into art. Ed also invented the art of gunpowder. He felt graphite was too streaky, so he went searching for something new. He found that soaking pellets in water washes away the salt and leaves a charcoal-like powder behind. The sulfur added a warm color and yet another dimension to his work. As for his subject matter: “There’s no guideline or rule as to what would make me want to select a particular word,” Ruscha says. His ideas have come from casual conversation, talk radio, even reading the dictionary. “I’m still mystified by it and I’m glad. Every so often something just bangs! I see it and I just feel like I have to hammer this in stone and make a picture out of it.”

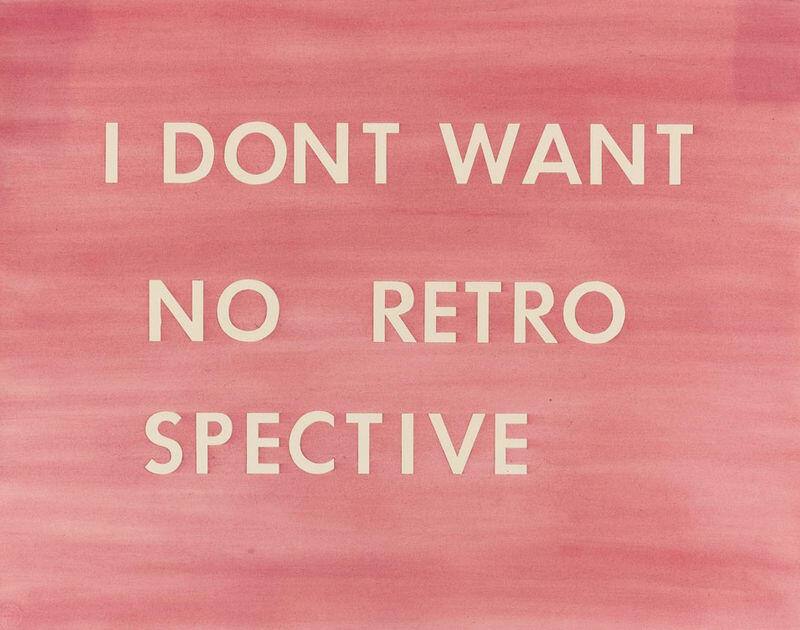

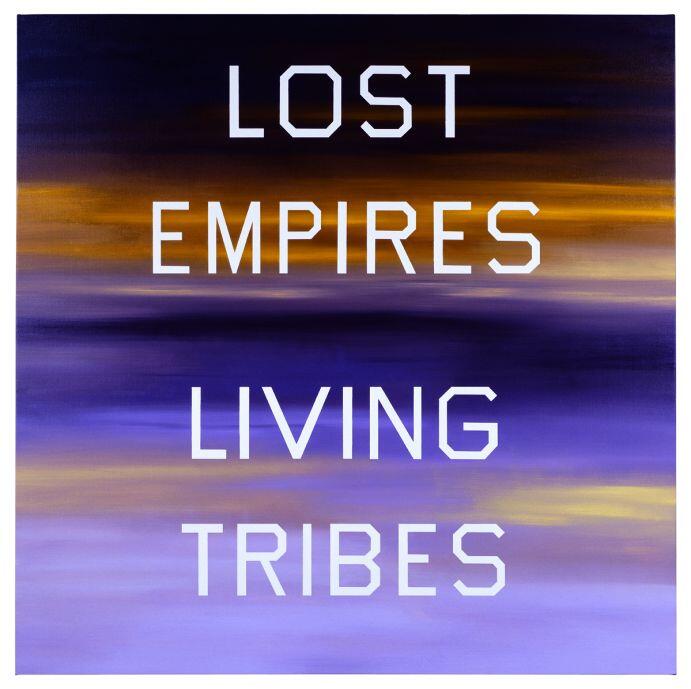

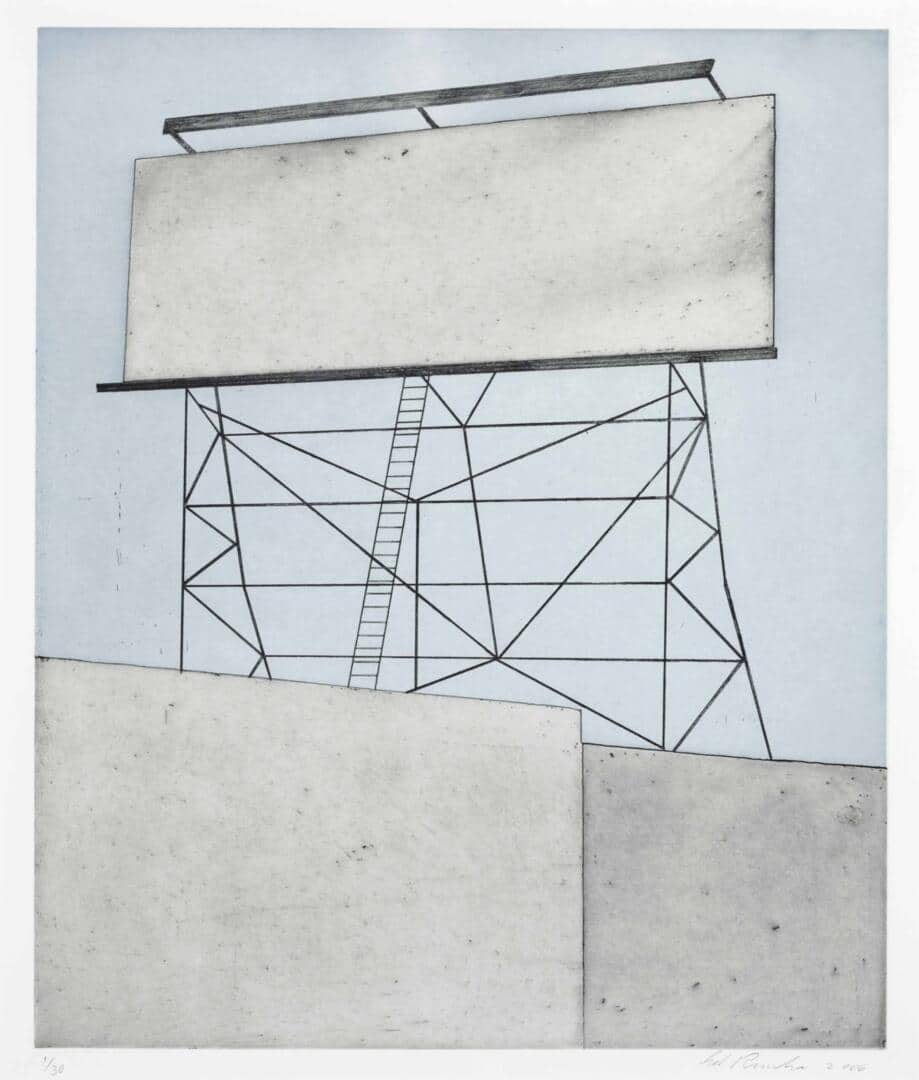

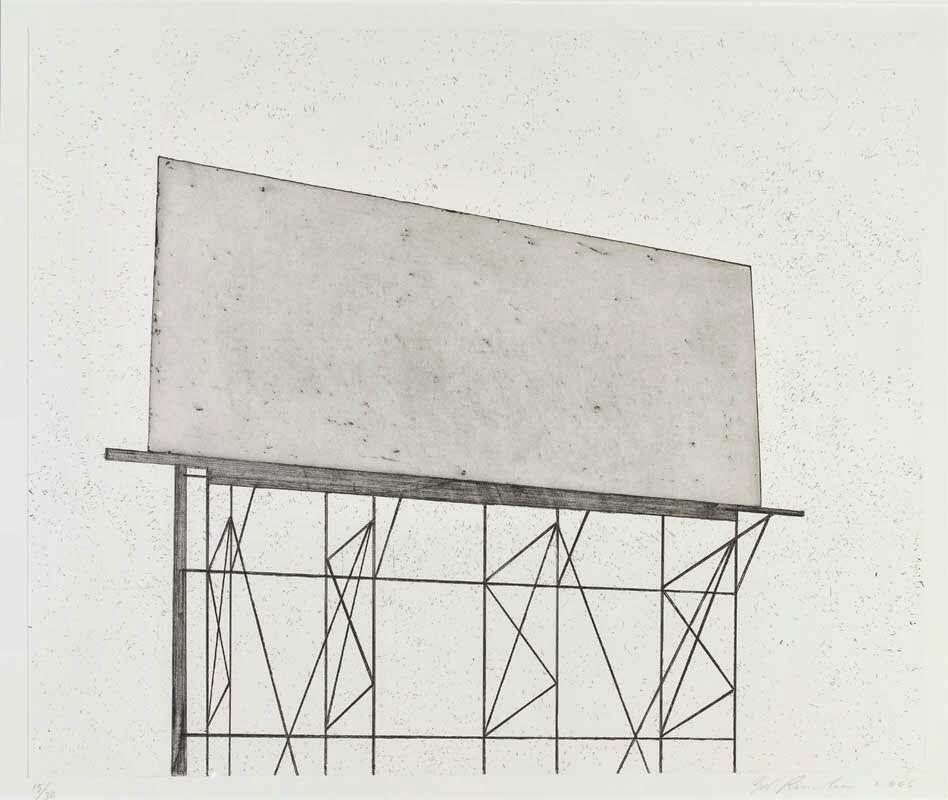

Ruscha’s “pictures” are powerful statements that turn to portraits if you trace the common thread woven through the decades of his work. From the mythical glitz and glamour of Hollywood to the barren landscape along Route 66 and his original study of the English language, Ruscha has always been painting a giant portrait of America. Ruscha has documented consumption, change and the consciousness of our culture. He’s shown us the country’s soul and its armpit without passing judgment. His artistic language is commentary on the basic values and commercial outgrowth that this society produces. “I do feel particularly American in this respect,” Ruscha says. “Some artists can feel universal and that their work might fit well in Paris or Rome or wherever, but I feel like all the history of America has sort of been funneled into my view of the entire world.”

With the explosion of contemporary art, Ed is proving to be a living legend. In November 2006, Christie’s held a Post War auction and five of Ruscha’s pieces went for a total of $1,575,600. All of them sold well above the high end estimate. One of them, Miniature America, sold for an astounding $576,000. Ed’s influence is everywhere. Many of today’s top young artists admit drawing inspiration from Ruscha’s work. From MoMA to the Smithsonian, the Getty, and around the world, the great museums have a Ruscha in their collections. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Director Neal Benezra organized one of Ruscha’s retrospectives in 2000. He attributes Ed’s success to the incredible growth of his work. “He hasn’t been stagnant at any time,” Benezra says. “The work has continued to evolve and surprise us. What he has done is put together a real career of work. If one of the measures of greatness is that you sustain your work and your creativity and your imagination and your achievement over a lifetime, well he really rates very, very high. We live in a culture of 15 minutes of fame, Ed has anything but that. He has a tremendously inventive body of work over several decades.”