WHERE IS THE ART WORLD GOING?

Written By BEN BAMSEY

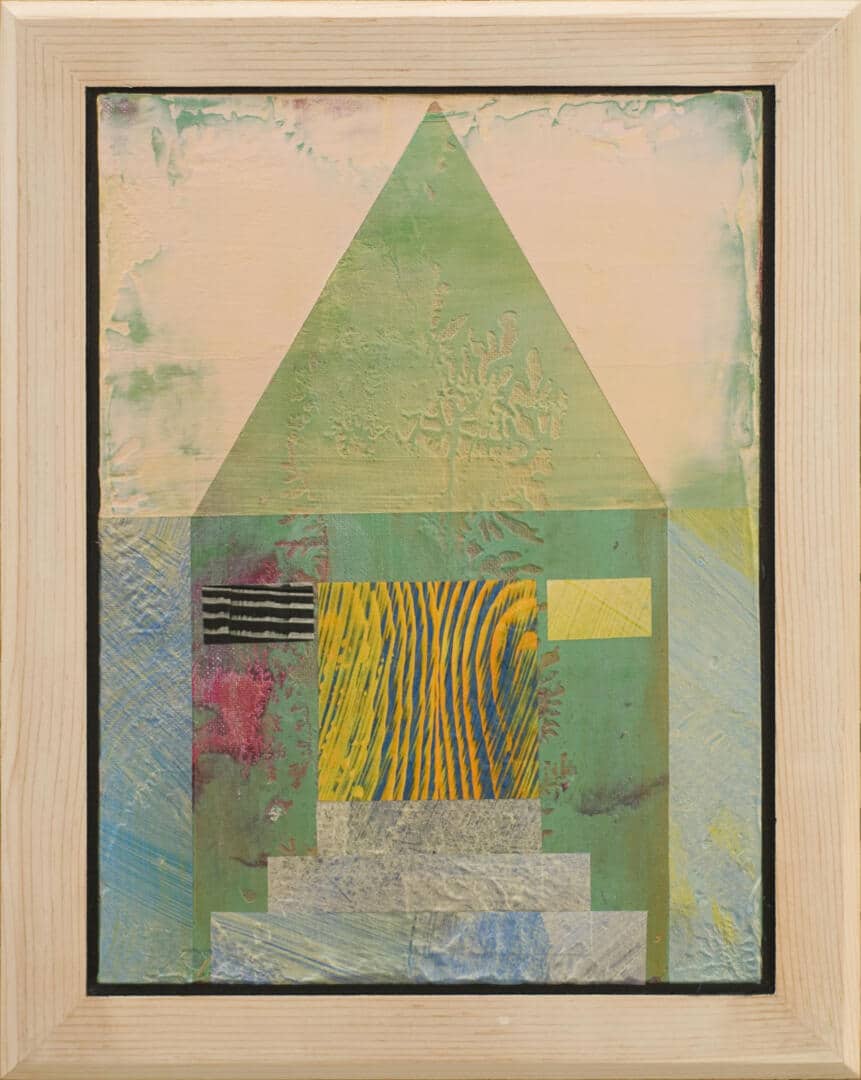

PHOTOGRAPHY MATT GORREK

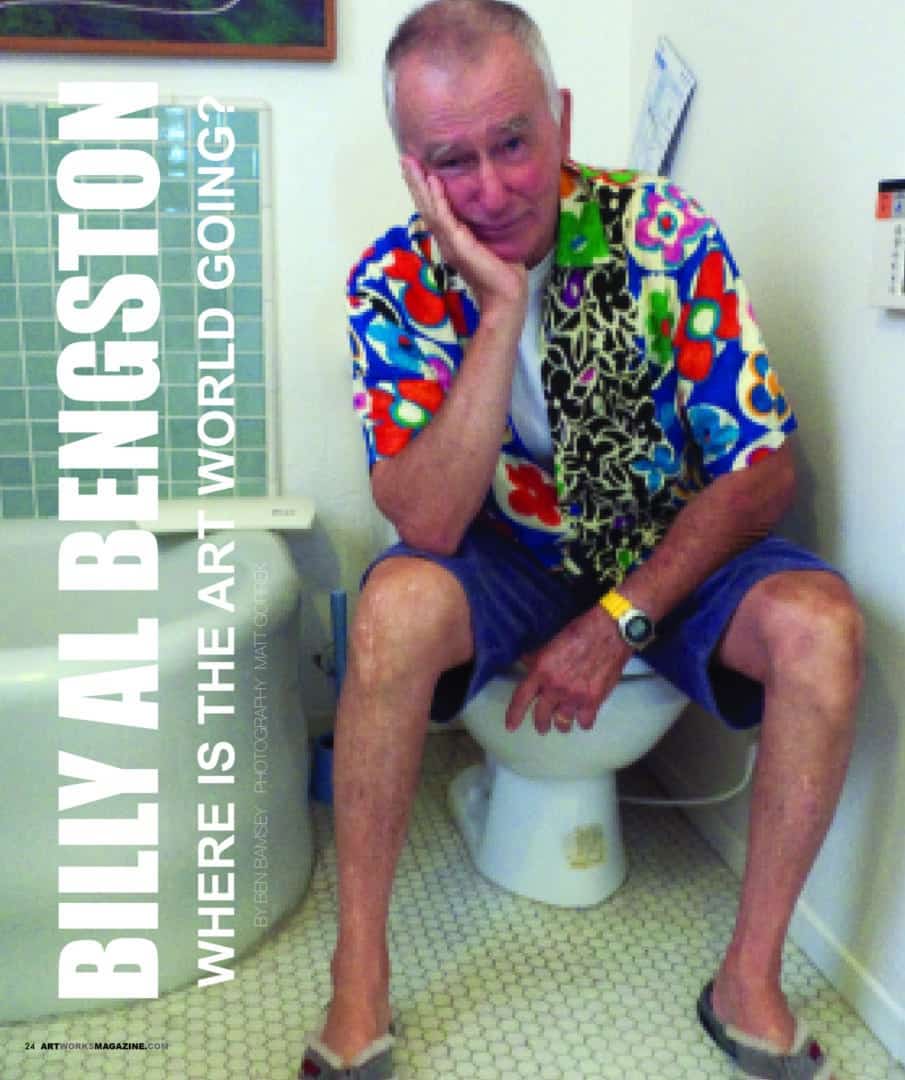

It’s hard to be misunderstood when an uncensored tongue wags like Billy Al Bengston’s. But the man and his legacy may be just that. His art isn’t fetching millions at auction, and his name doesn’t radiate in Hollywood neon like some others. It should, but all that glitz just makes him limp anyway. “I don’t care about the big money, and that’s the reason why I’m not even close to successful,” Bengston says knowing how most people measure it. “I hate the idea of chasing money. I hate chasing fame. I hate all of that shit, though I highly admire people that can do it. Frank Gehry can do it like a champ. But most of ‘em just turn into dicks.” Nothing chafes Bengston quite like the term ‘artist.’ “What the fuck is an artist today? In 1950, it used to mean something… You were either queer, or did a lot of drugs, or wore a beret. It meant you were odd and pretentious and arrogant, thinking that you made ‘art.’ That suited me fine. It ain’t that way anymore.”

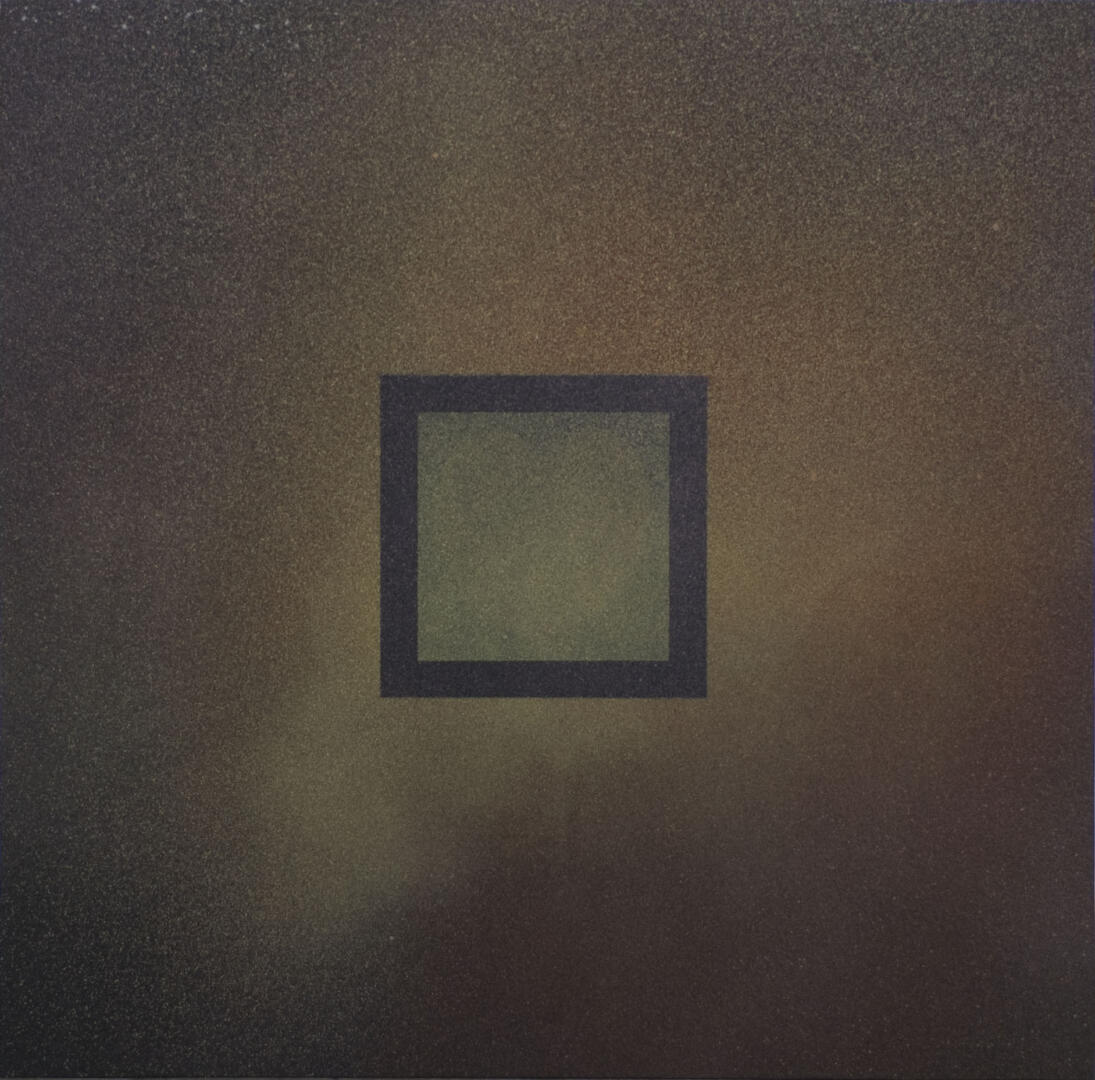

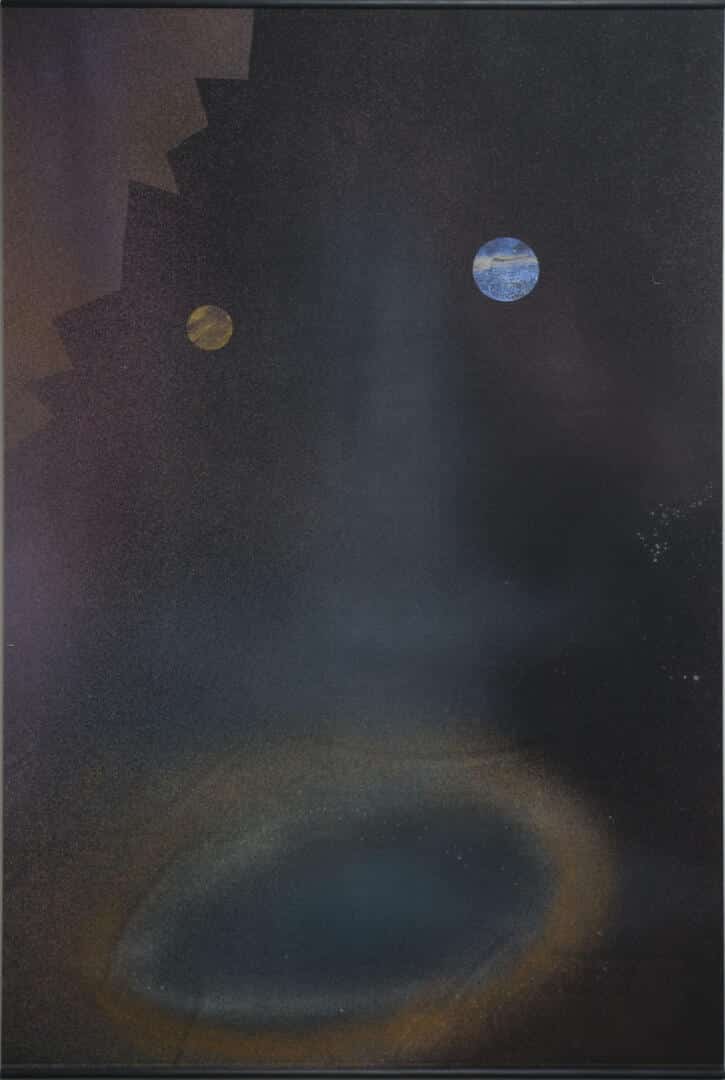

These days, Bengston contends that the market is oversaturated with recycled imagery and ideas, along with gangbang art factories ruling the roost. “Currently, most of the people respected in the arts are the ones who manipulate public opinion to achieve celebrity, fame and fortune,” he adds. That’s backwards thinking, according to Bengston, who has always been more interested in stretching creative limits than counting cash. Thanks to his unique vision he’s been called an artistic trendsetter and a fearless inventor who helped put California art on the map. A lifelong gearhead, Bengston was one of the first to ditch traditional oil paint for automobile lacquer, and in an extra effort to make industrial strength art, he switched canvas for aluminum. By using soft colors and denting the surface with a hammer, he also achieved reflection and translucency in a way that had never been done before. Bengston’s peers have marveled at his ideas, but critically and commercially they’ve often been crapshoots of frozen snake eyes. “Everybody wants identifiable images, and they say, ‘Well, I can’t see it. There’s reflection.’ Well, that’s the fucking idea!” he shouts. “And therein lies the downfall of my particular appeal. It’s a dead end, because it’s too hard for people to understand something that doesn’t relate to them, sort of like the Theory of Relativity. Most people would rather have a picture of the dog rather than live with the animal.” Ultimately, it’s impossible to pin down a Billy Al Bengston piece, because each viewing is a different adventure. But just like human relationships, the people we tend to love the most are the ones we can’t label.

engston lives in the old, three-story Venice News building just blocks from the graffiti walls, weightlifting stations and daily freak show that clutter Venice Beach. The energy is as bright as the Los Angeles daylight giving off a constant creative buzz. Bengston’s closetful of Hawaiian shirts only adds to the atmosphere. His garage has tricked out energy-efficient hybrids with custom-made yellow interiors, plus he reads Dan Neil’s car reviews like they are Scripture and he’s in Seminary. In the kitchen, a $3,000 cappuccino machine gets plenty of use, but true to form, Bengston found a way to tinker with the recipe. He ground up the beans, added condensed milk and gelatin, and then used a Pyrex mold to turn the concoction into a highly-caffeinated, Cosby-perfect dessert that he calls “espresso jell-O.”At 76, Billy Al Bengston gets a high out of living. His skin is tight, stomach trim and most of his hair is still there. His mind is like the Energizer bunny on speed, and opinions ping off the walls like bouncy balls going Mach 10… “Washington is just a culture of crooks making a living out of lying,” he says. “It’ll be interesting to see if Obama can make some real changes, but I really think he’s just shoveling shit against the tide.” Bengston views religion like hot farts – often the silent, but very violent reasons used for unjustified warfare. When asked why the public’s collective sniffer doesn’t work, he explains, “I just think the concept of right is negative to most semi-intellectual people.” One of this country’s most significant problems, says Bengston, is its work ethic. “The thing with the people of Arizona and the immigration of Mexicans – stop complaining! Don’t hire ‘em. It’s simple. If you don’t hire them, they’re not coming.”Art history is a very serious subject at the Bengston household. His walls serve as shrines to some of the greatest painters California has known – Ken Price and Craig Kauffman artwork from the late 1950’s, several John Altoons, even a Ruscha or two and Gehry furniture along with a retrospective of his own signature pieces and ceramics. Bengston could retire his whole family on what he has hanging, but that’s so far beyond missing the point. “With the level of education we have today, which is only a modicum of education, it’s just enough to make you think that if you’re rich, you’re going to be happy. So people talk about the cost of everything, rather than the value. I traded a painting with an artist one time, an equal trade of about $300. His painting ended up becoming quite ‘valuable,’ and I had it hanging up for a long time. People would come over and say, ‘God, do you know how much that’s worth?’ They never SAW it.” One day, Bob Graham came to Billy Al’s house and asked him what happened to that great painting. “I told him, ‘I sold it! Turns out, it was worth a lot of money like everyone kept saying.’ And Bob said, ‘Oh, it lost its value.’”

Bengston’s wealth of artistic knowledge began at Manual Arts High School in downtown L.A., along with Jackson Pollock and Robert Motherwell. The school had body shops, foundries, drawing and sculpture classes and the only live, nude models in the state. “I thought that that would be a really good thing,” Bengston recounts, “and then I saw the models. I started out in the front row, but quickly moved further and further away. I learned that most people should keep their clothes on, especially if they’re over fifty.” Instead of bare skin, it was clay that captured Bengston’s attention. He graduated and moved on to Los Angeles City College, California College of Arts & Crafts and Otis Art Institute. He took classes from Richard Diebenkorn and Sabro Hasegawa, but his most significant training came under the tutelage of legendary ceramicist Peter Voulkos. “He was an incredible teacher. I learned so much from him,” he says, “but I couldn’t stand ceramicists. Oh fuck are they boring.”It was pretty clear that Bengston didn’t blend in with the potter wheel crowd. He was a jock and a damn good surfer who was much more interested in talking about a crashing wave than how a teacup poured. Voulkos nicknamed him “Moondoggie” even before Frederick Kohner made the character popular as Gidget’s carefree boyfriend in his books and movies. Bengston changed the moniker to Moontang, “because it rhymed with poontang,” naturally. Bengston still enjoys crafting plates and fine art pieces out of his aptly titled studio, Moontang Kilns, but as for a full-time career in the field, he folded those cards long ago. “Being as competitive as I was, and still am, I just realized that I am never, ever, ever gonna make a patch on (Voulkos’s) ass. He’s as good as it’ll ever get, and I knew it. But I could paint better, so I thought, ‘Well, I guess I’ll do that.’” So then and there, at the tender age of 22, Billy Al Bengston decided to become an “artist.”

It was a chance run-in with Ed Kienholz that gave him the lucky break he needed. Kienholz was a crafty guy who loved meeting people. He was a hustler to all that knew him well. At the time, he had a tiny gallery near a theatre on Sunset Boulevard. Kienholz showed Bengston the back door of the theatre where they snuck in together, and later ushered him in the front door at Ferus, giving Bengston the third show ever at that iconic gallery. Kienhloz, who’d partnered with Walter Hopps to open Ferus Gallery, was in the business of recruiting top-notch, eager artists, and in addition to Bengston, landed the likes of John Altoon, Craig Kauffman, and San Francisco-based painters Hassel Smith, Jay DeFeo and Frank Lobdell. Together these men began brewing a creative synergy that, suddenly, had the art world toasting the West Coast.The only way to describe the bond between the Ferus artists of the 1950’s is to call them what they were – an art gang. They were young, hip and had crisp chips on their shoulders. “It was seriously competitive amongst us,” Bengston says. “We would have probably killed each other, but we’d kill anybody who crossed our path first.”

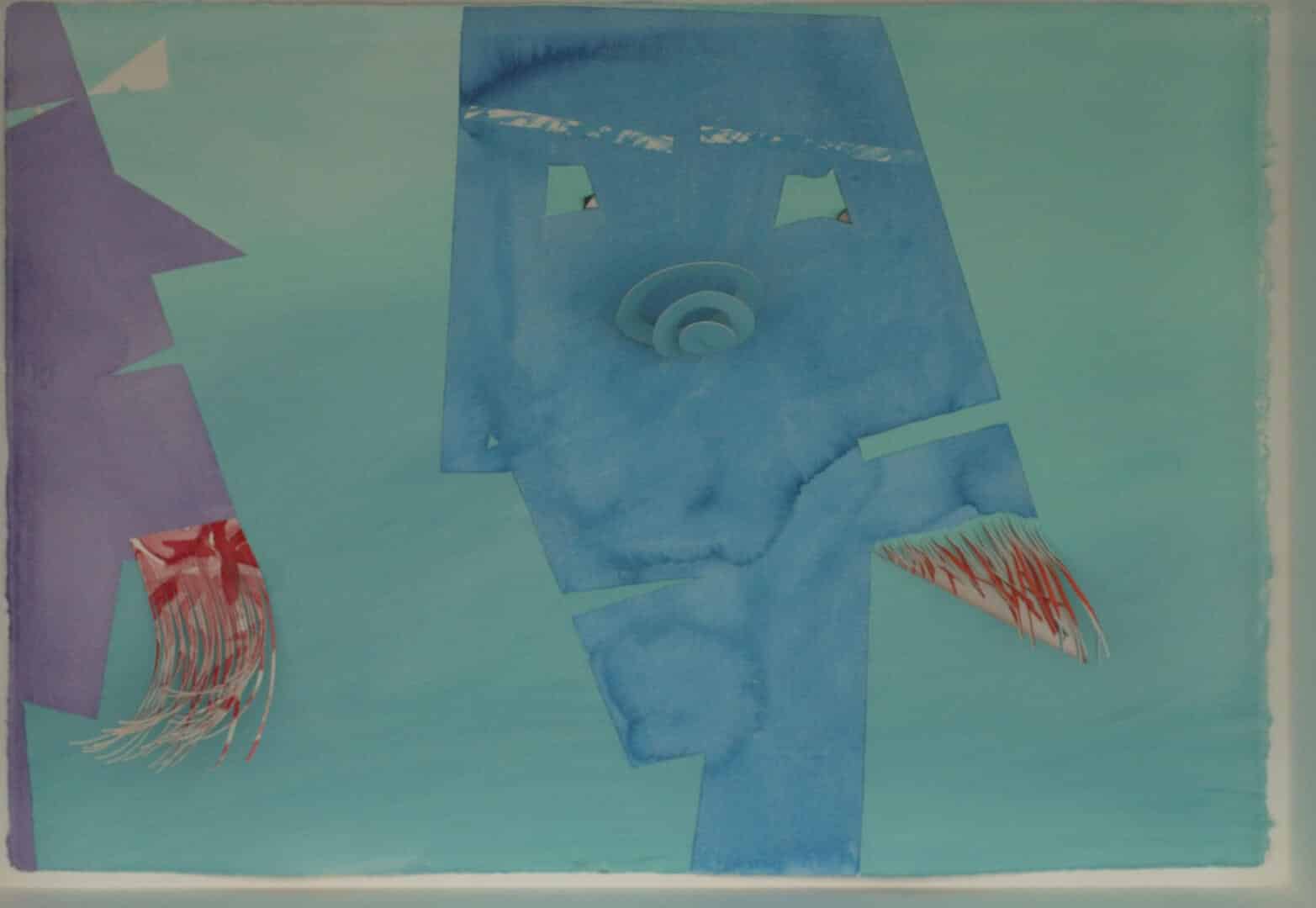

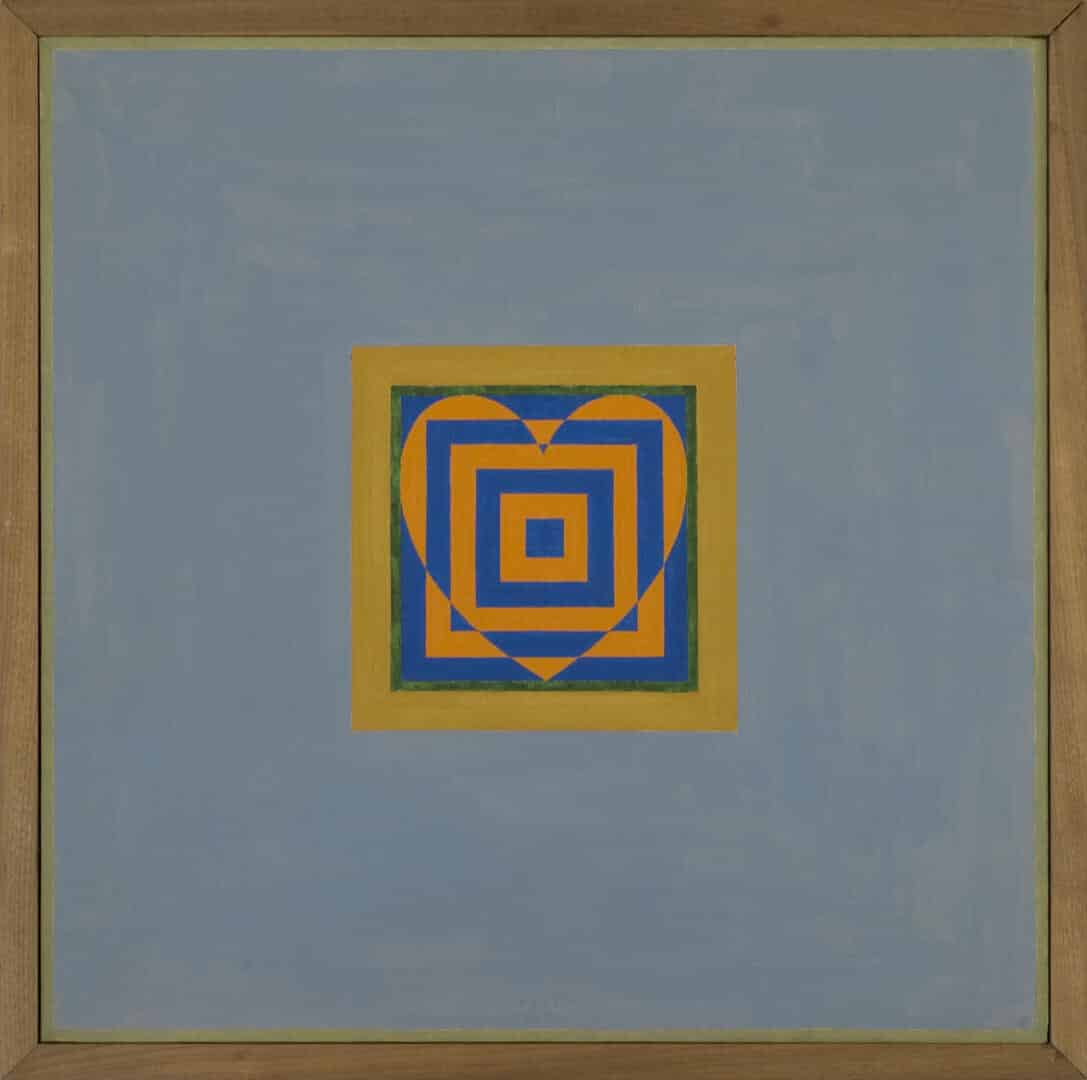

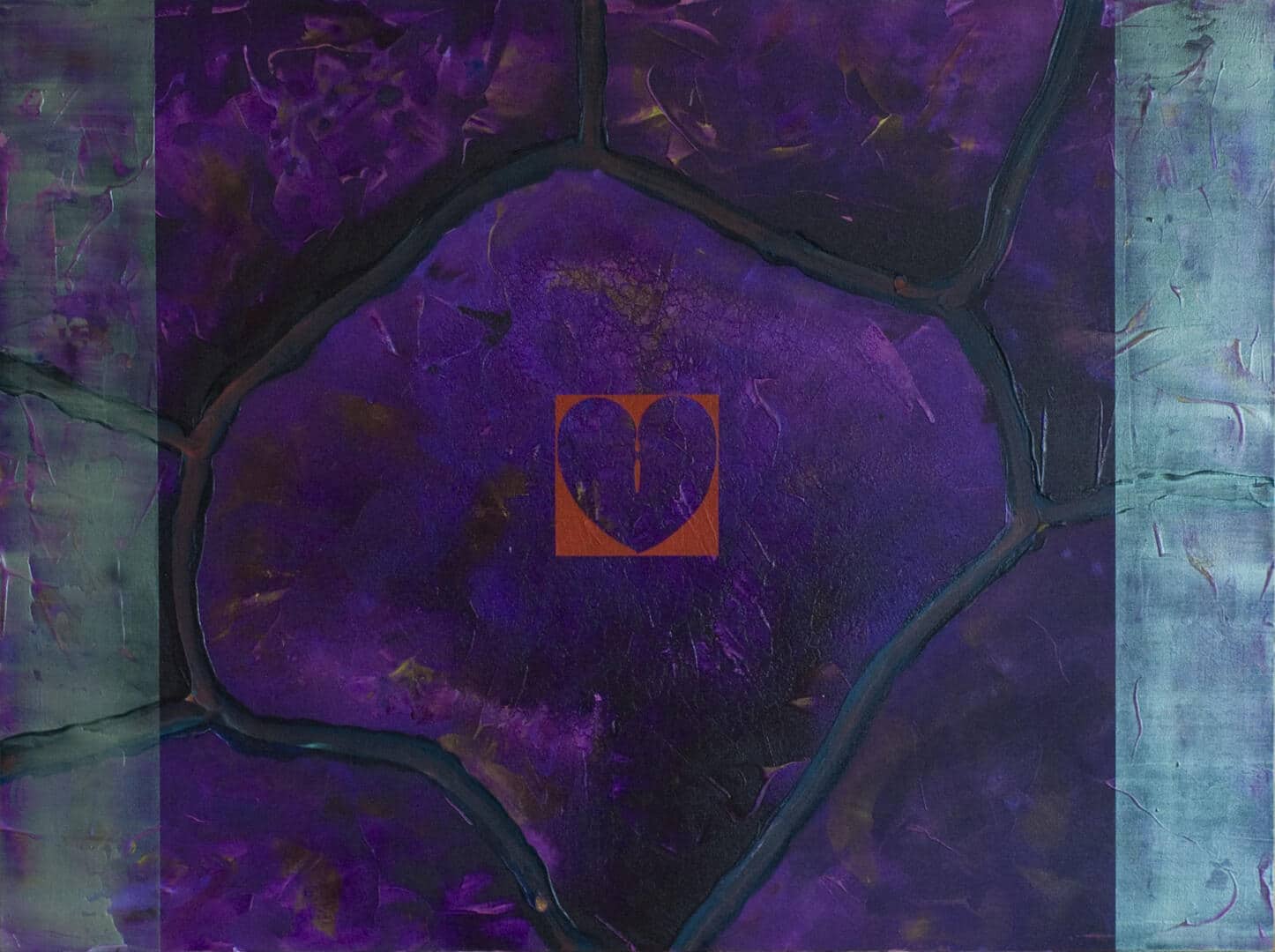

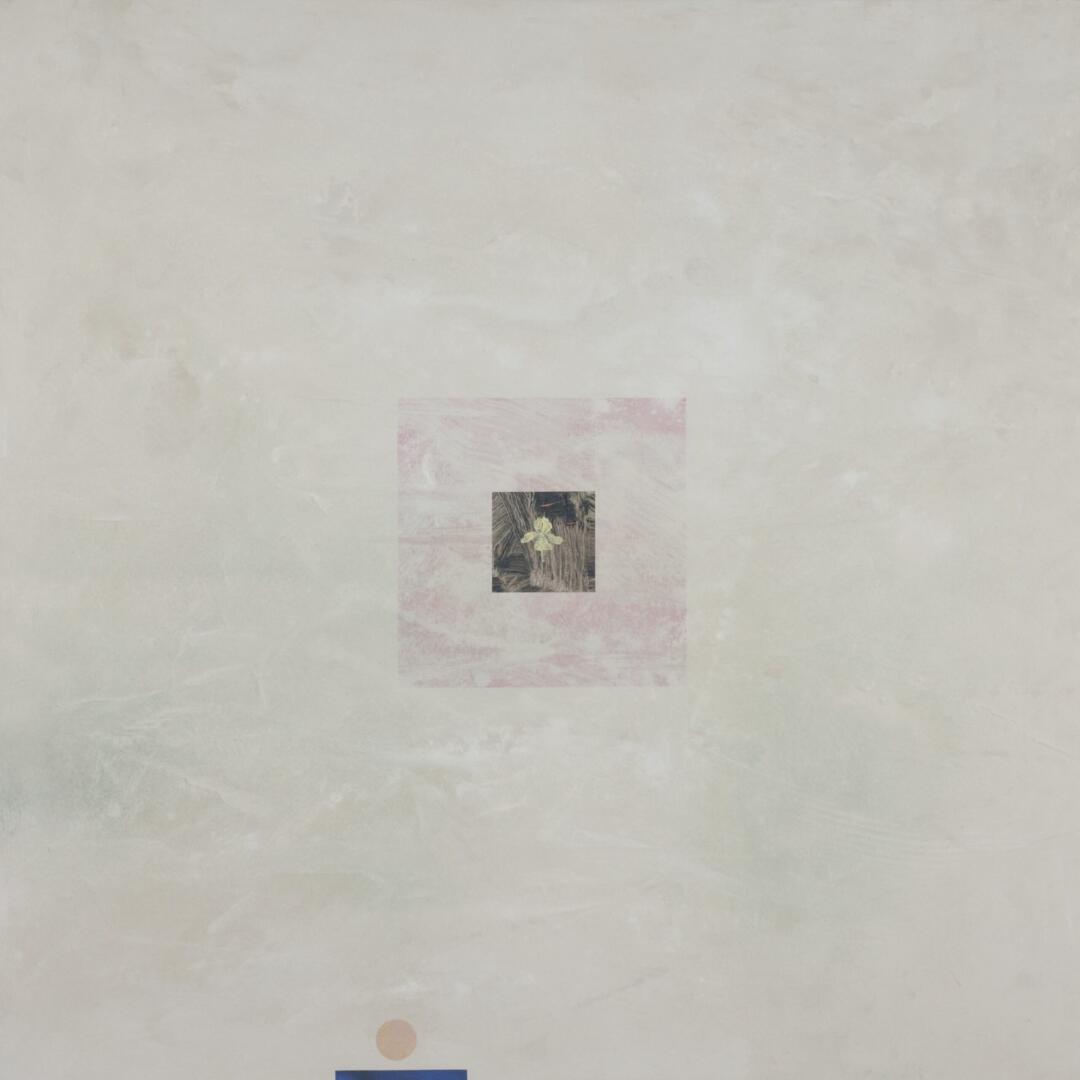

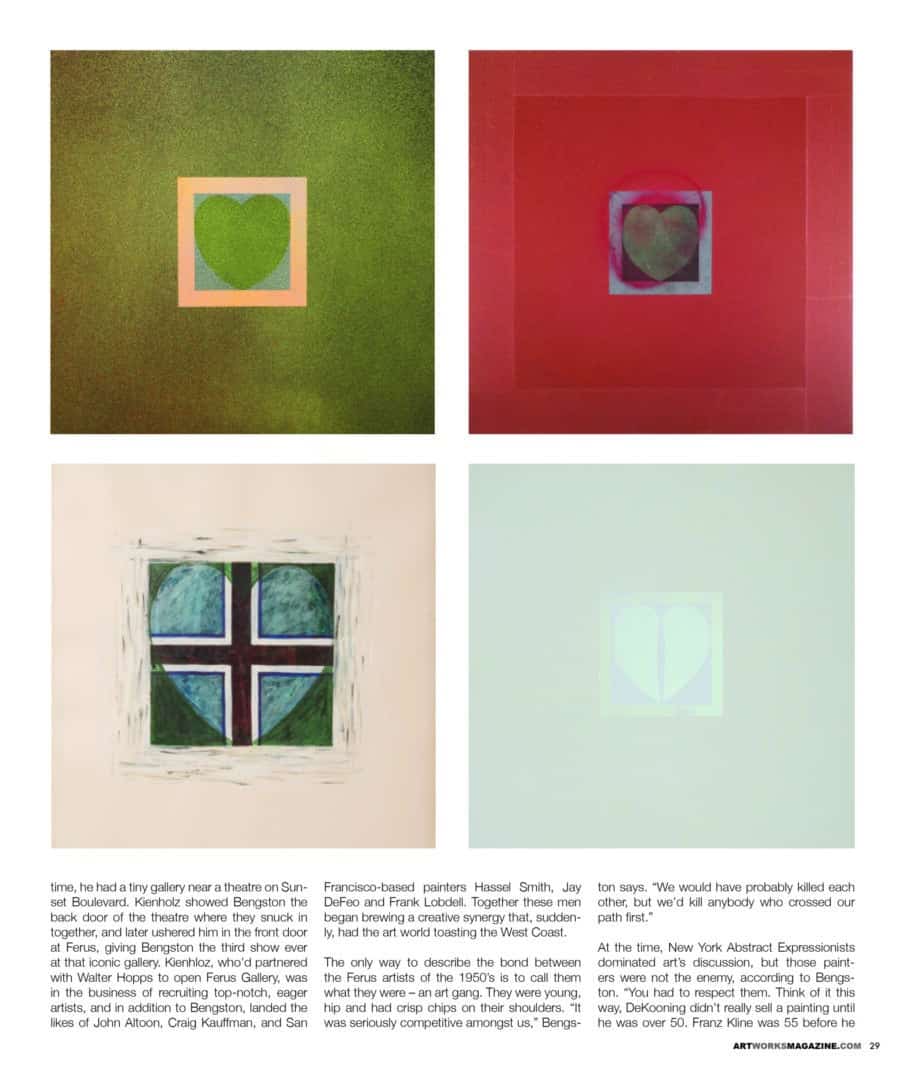

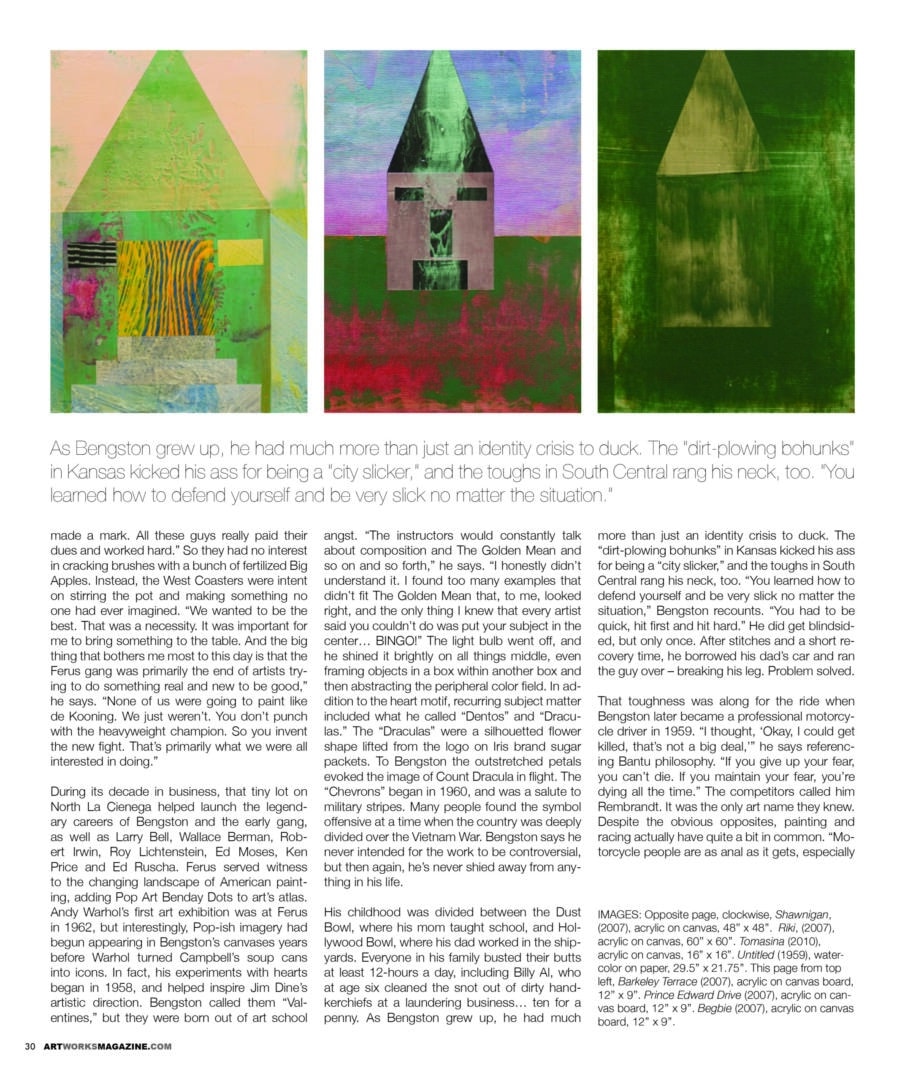

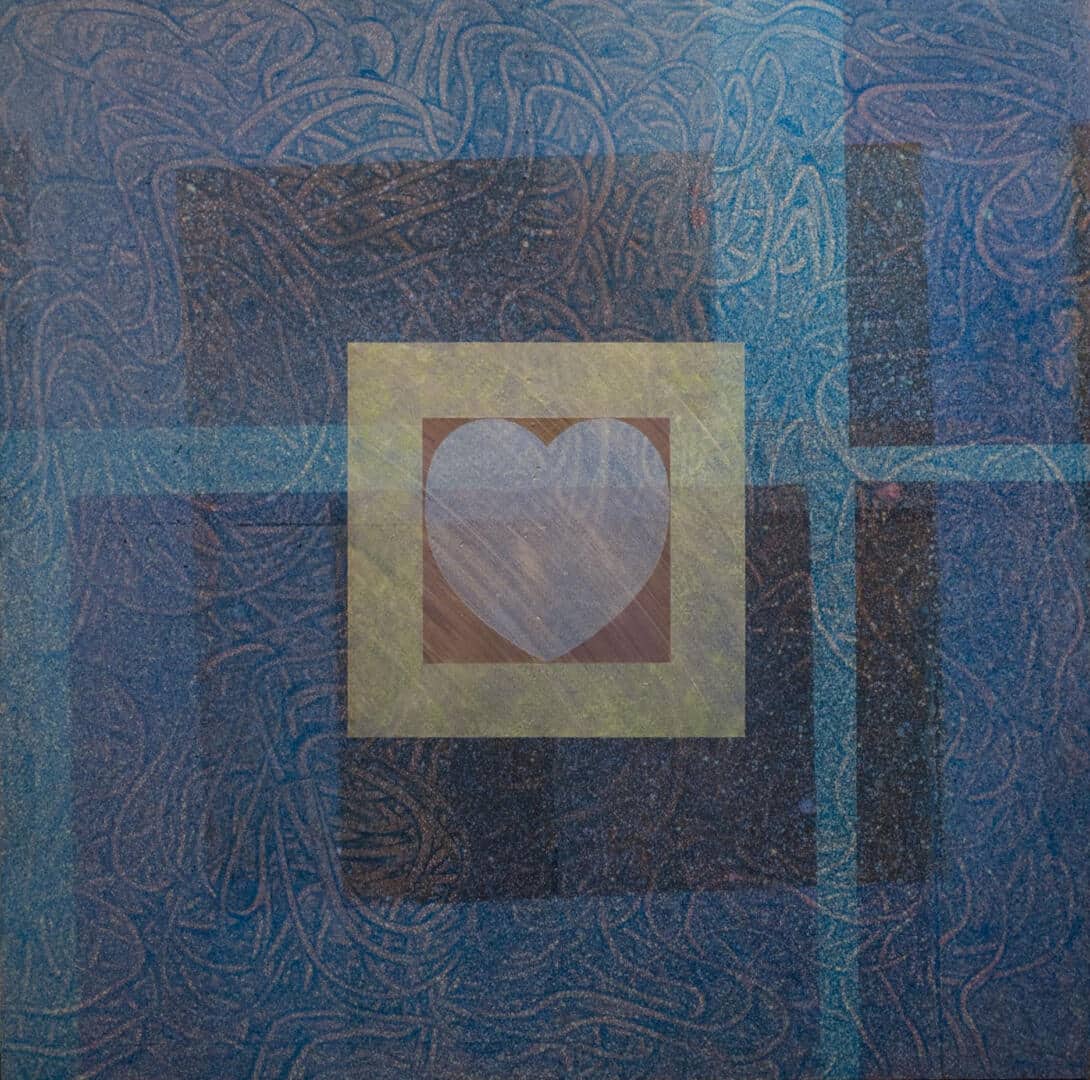

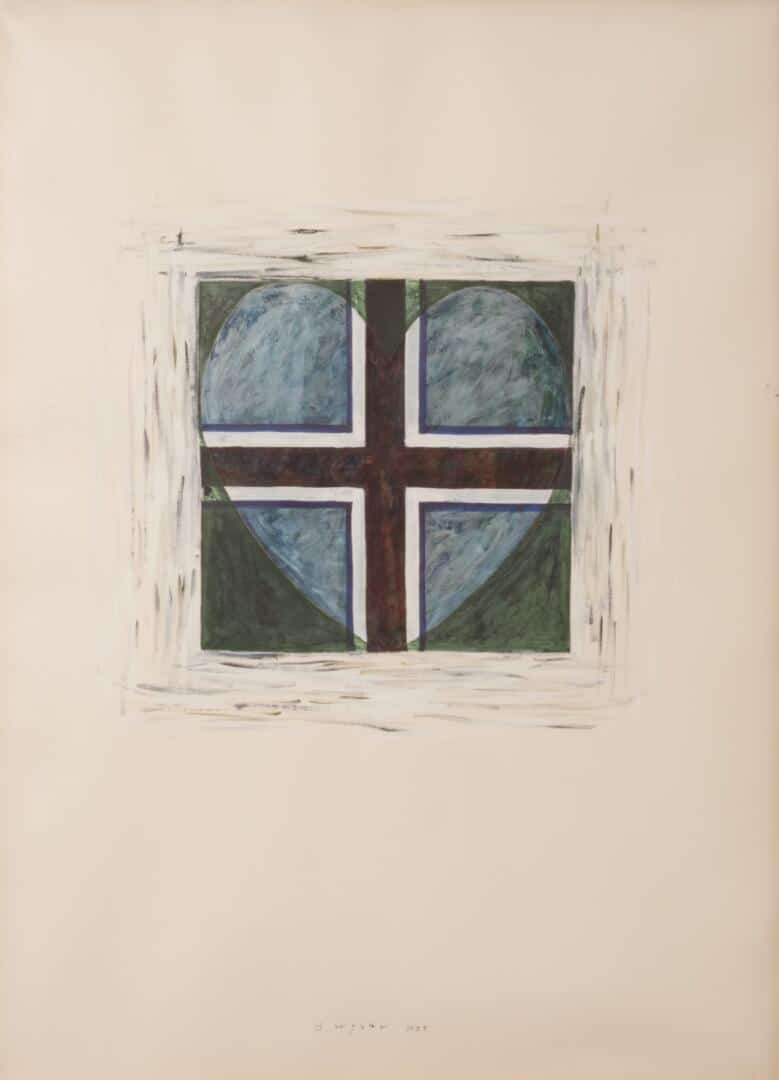

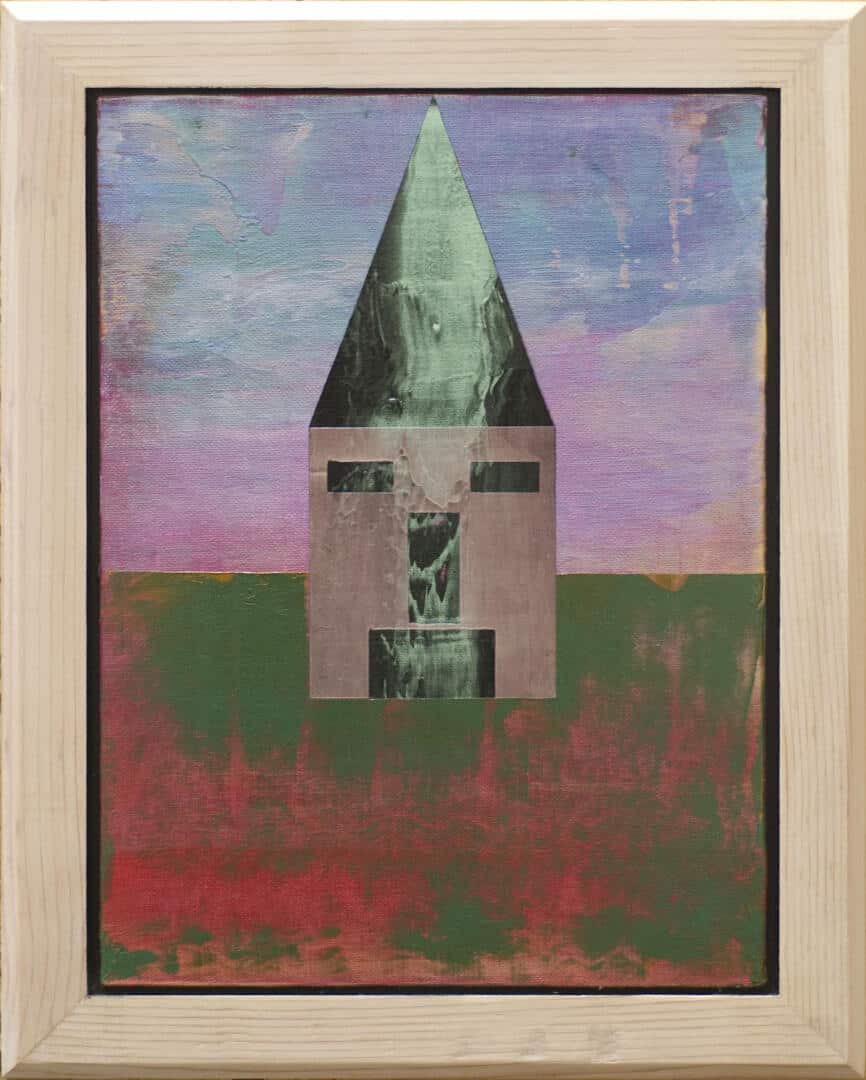

At the time, New York Abstract Expressionists dominated art’s discussion, but those painters were not the enemy, according to Bengston. “You had to respect them. Think of it this way, DeKooning didn’t really sell a painting until he was over 50. Franz Kline was 55 before he made a mark. All these guys really paid their dues and worked hard.” So they had no interest in cracking brushes with a bunch of fertilized Big Apples. Instead, the West Coasters were intent on stirring the pot and making something no one had ever imagined. “We wanted to be the best. That was a necessity. It was important for me to bring something to the table. And the big thing that bothers me most to this day is that the Ferus gang was primarily the end of artists trying to do something real and new to be good,” he says. “None of us were going to paint like de Kooning. We just weren’t. You don’t punch with the heavyweight champion. So you invent the new fight. That’s primarily what we were all interested in doing.”During its decade in business, that tiny lot on North La Cienega helped launch the legendary careers of Bengston and the early gang, as well as Larry Bell, Wallace Berman, Robert Irwin, Roy Lichtenstein, Ed Moses, Ken Price and Ed Ruscha. Ferus served witness to the changing landscape of American painting, adding Pop Art Benday Dots to art’s atlas. Andy Warhol’s first art exhibition was at Ferus in 1962, but interestingly, Pop-ish imagery had begun appearing in Bengston’s canvases years before Warhol turned Campbell’s soup cans into icons. In fact, his experiments with hearts began in 1958, and helped inspire Jim Dine’s artistic direction. Bengston called them “Valentines,” but they were born out of art school angst. “The instructors would constantly talk about composition and The Golden Mean and so on and so forth,” he says. “I honestly didn’t understand it. I found too many examples that didn’t fit The Golden Mean that, to me, looked right, and the only thing I knew that every artist said you couldn’t do was put your subject in the center… BINGO!” The light bulb went off, and he shined it brightly on all things middle, even framing objects in a box within another box and then abstracting the peripheral color field. In addition to the heart motif, recurring subject matter included what he called “Dentos” and “Draculas.” The “Draculas” were a silhouetted flower shape lifted from the logo on Iris brand sugar packets. To Bengston the outstretched petals evoked the image of Count Dracula in flight. The “Chevrons” began in 1960, and was a salute to military stripes. Many people found the symbol offensive at a time when the country was deeply divided over the Vietnam War. Bengston says he never intended for the work to be controversial, but then again, he’s never shied away from anything in his life.

His childhood was divided between the Dust Bowl, where his mom taught school, and Hollywood Bowl, where his dad worked in the shipyards. Everyone in his family busted their butts at least 12-hours a day, including Billy Al, who at age six cleaned the snot out of dirty handkerchiefs at a laundering business… ten for a penny. As Bengston grew up, he had much more than just an identity crisis to duck. The “dirt-plowing bohunks” in Kansas kicked his ass for being a “city slicker,” and the toughs in South Central rang his neck, too. “You learned how to defend yourself and be very slick no matter the situation,” Bengston recounts. “You had to be quick, hit first and hit hard.” He did get blindsided, but only once. After stitches and a short recovery time, he borrowed his dad’s car and ran the guy over – breaking his leg. Problem solved.That toughness was along for the ride when Bengston later became a professional motorcycle driver in 1959. “I thought, ‘Okay, I could get killed, that’s not a big deal,’” he says referencing Bantu philosophy. “If you give up your fear, you can’t die. If you maintain your fear, you’re dying all the time.” The competitors called him Rembrandt. It was the only art name they knew. Despite the obvious opposites, painting and racing actually have quite a bit in common. “Motorcycle people are as anal as it gets, especially when it comes to equipment. That’s something that carried over to painting,” he says. “You have to keep your tools in order. If you lose your tools, you can’t do the work. In other words, it’s hard to beat someone with broken strings.” You can’t beat them with a broken back either. And that’s exactly what happened to Bengston on a dirt track in Ascot at the age of 29. He was riding second when the guy he was about to pass on the outside slid out. Bengston swerved to avoid him and went from 70 mph to 0 in a flash. “That’s when the wall was the wall,” he points out. Two months later he was racing again, but the injury slowed him down in a sport where split seconds matter. So he gave up his license at the end of the season. “Don’t hitch a racehorse to a plow.”There was no replacing the immediate thrill of wheel-to-wheel turns on the track, but Bengston vowed to make the brushstrokes he executed in his studio just as exciting. He argues that before Impressionism, most artists were hired hands for kings, queens and the Pope, forced to paint in the name of a land or the Lord. “And then 20th century painters, even non-representational and abstract artists, spent their time working towards something that people could recognize.” In other words, they were focused on communicating, rather than painting a picture. “My method has always been – ‘Okay, I’m going to paint a picture,’” he says. “It’s not supposed to be about: ‘Oh, I recognize that,’ or ‘it looks like Harry,’ or ‘my aunt would like that painting of a dog.’ To me, a picture is just supposed to sit there and be something to look at. You’re never supposed to know what it is. Once you know what it is, it’s something else; a memory.”

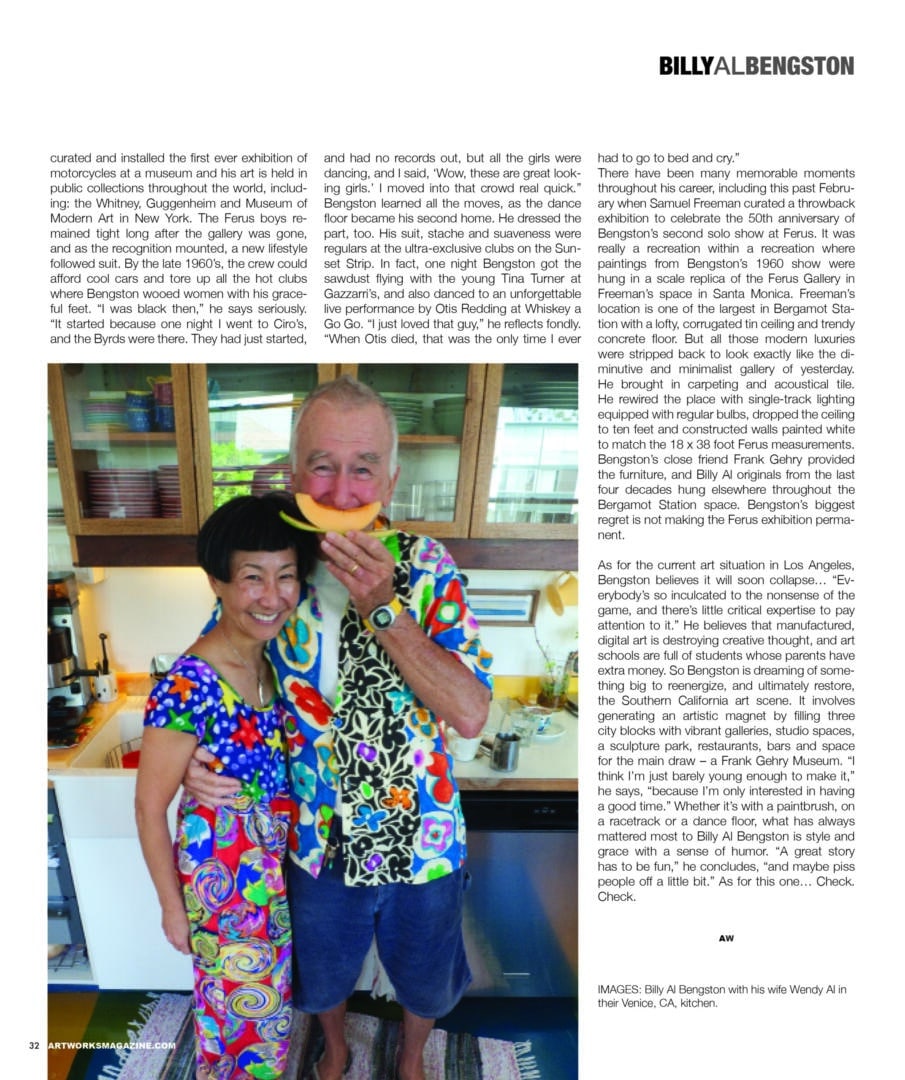

His advice to people wanting to paint are words that he has most definitely lived by: “To be an artist, change everything.” That means independence of vision, freedom from genre and mold and a willingness to find and explore an authentic voice. Early in his career, he noticed that 50+ year old canvases all had cracks on them. As he puts it, “That’s why there are more restorers out there, than there are painters.” So he asked himself, “What is oil paint? It’s minerals ground up in what I refer to as salad oil that’s then painted on a canvas, which is essentially a rag.” During his racing days, Bengston sprayed plenty of bikes to make a buck here and there. If he used oil paint, he’d have to repeat the process each week. So he got to thinking… “Original Rolls Royces were painted with nitrocellulose, lacquer, banana oil and brushes – sanded between each coat.” It’s why a 1920’s Rolls Royce is still in mint condition without any touchups. With a hearty laugh Bengston says, “So I thought, ‘I’ll go that direction.’”The turn down Original Street was paved with many more inventions. All the Abstract Expressionist rhetoric focused on big, bigger and beyond the frame. “Well, what the fuck does that mean?” Bengston pondered. “Big is only relative to where you are standing. So I thought, ‘Okay, how do you truly make art big?’ Well, you put air in it, making it hard for a viewer to really focus. So, that’s what reflection is all about.” Again, Bengston viewed this phenomenon every time he raced, as the sun danced across his metal motorcycle. His next artistic step in 1965 also borrowed from sport and seemed natural. “Then, I still wanted to go beyond the frame, and that’s when I thought about denting aluminum sheets,” he continues. So, he broke out the hammers and bashed away. The resulting bumps and ridges combined with his palette of soft colors, allowing the translucency of light to render his surfaces without boundary. While these moves were revolutionary within the industry, his bandwagon remains one heck of a lonely ride. “Few got it,” he says. “It all went over like a turd in a punchbowl.”Of course, Bengston has always had an audience of foresters in a one-tree world. He made plenty of money then, and much of his work sells for six figures now. Among his numerous accolades: Bengston is the youngest artist to have a retrospective at LACMA, he earned the first National Endowment For the Arts grant, curated and installed the first ever exhibition of motorcycles at a museum and his art is held in public collections throughout the world, including: the Whitney, Guggenheim and Museum of Modern Art in New York. The Ferus boys remained tight long after the gallery was gone, and as the recognition mounted, a new lifestyle followed suit. By the late 1960’s, the crew could afford cool cars and tore up all the hot clubs where Bengston wooed women with his graceful feet. “I was black then,” he says seriously. “It started because one night I went to Ciro’s, and the Byrds were there. They had just started, and had no records out, but all the girls were dancing, and I said, ‘Wow, these are great looking girls.’ I moved into that crowd real quick.” Bengston learned all the moves, as the dance floor became his second home. He dressed the part, too. His suit, stache and suaveness were regulars at the ultra-exclusive clubs on the Sunset Strip. In fact, one night Bengston got the sawdust flying with the young Tina Turner at Gazzarri’s, and also danced to an unforgettable live performance by Otis Redding at Whiskey a Go Go. “I just loved that guy,” he reflects fondly. “When Otis died, that was the only time I ever had to go to bed and cry.”

There have been many memorable moments throughout his career, including this past February when Samuel Freeman curated a throwback exhibition to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Bengston’s second solo show at Ferus. It was really a recreation within a recreation where paintings from Bengston’s 1960 show were hung in a scale replica of the Ferus Gallery in Freeman’s space in Santa Monica. Freeman’s location is one of the largest in Bergamot Station with a lofty, corrugated tin ceiling and trendy concrete floor. But all those modern luxuries were stripped back to look exactly like the diminutive and minimalist gallery of yesterday. He brought in carpeting and acoustical tile. He rewired the place with single-track lighting equipped with regular bulbs, dropped the ceiling to ten feet and constructed walls painted white to match the 18 x 38 foot Ferus measurements. Bengston’s close friend Frank Gehry provided the furniture, and Billy Al originals from the last four decades hung elsewhere throughout the Bergamot Station space. Bengston’s biggest regret is not making the Ferus exhibition permanent.As for the current art situation in Los Angeles, Bengston believes it will soon collapse… “Everybody’s so inculcated to the nonsense of the game, and there’s little critical expertise to pay attention to it.” He believes that manufactured, digital art is destroying creative thought, and art schools are full of students whose parents have extra money. So Bengston is dreaming of something big to reenergize, and ultimately restore, the Southern California art scene. It involves generating an artistic magnet by filling three city blocks with vibrant galleries, studio spaces, a sculpture park, restaurants, bars and space for the main draw – a Frank Gehry Museum. “I think I’m just barely young enough to make it,” he says, “because I’m only interested in having a good time.” Whether it’s with a paintbrush, on a racetrack or a dance floor, what has always mattered most to Billy Al Bengston is style and grace with a sense of humor. “A great story has to be fun,” he concludes, “and maybe piss people off a little bit.” As for this one… Check. Check.