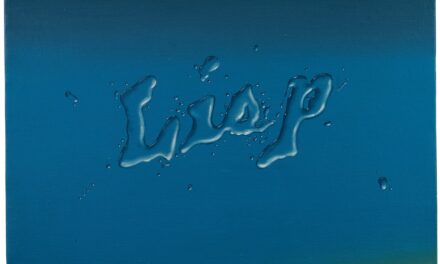

BETH VAN HOESEN

Written by: ERIN CLARK

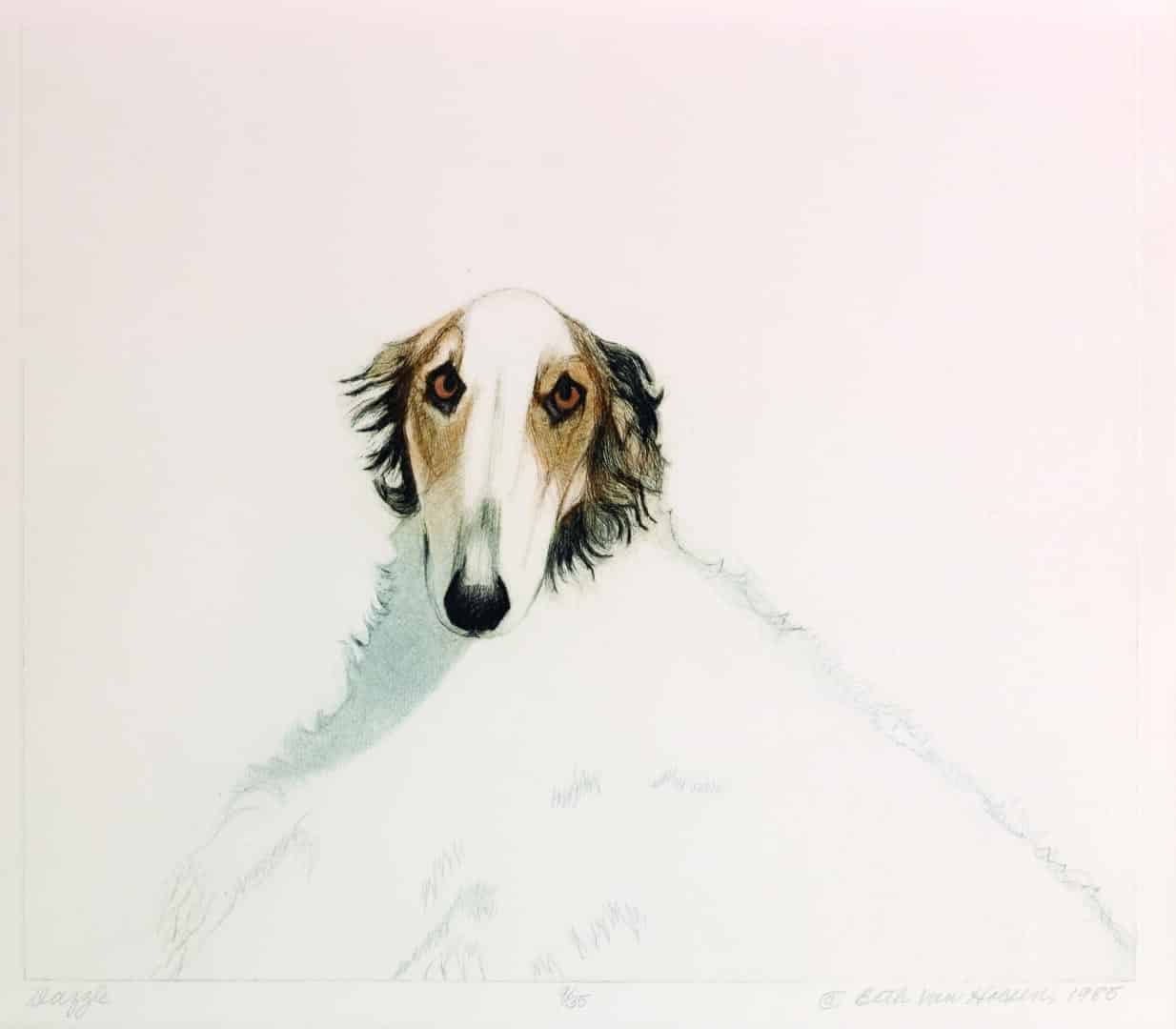

All of us at one time or another have come across a person we thought we knew, either by reputation or preconceived notion, only to learn that we were dead wrong, or at the very least hasty in our assessment. That’s how I feel about Bay Area artist Beth Van Hoesen. Known first as “the flower artist” and then later as “the animal artist,” Van Hoesen has had to fight the art world’s prejudice against any subject matter than could be considered in the least bit endearing. Her supporters will argue that her animal portraits and still life flowers do have a unique edge, but in my opinion there is no getting around it – they are charming. And what’s wrong with that? I think the better argument for her place in the upper echelons of Bay Area art is in her masterful technique, superior draftsmanship and a body of work that goes beyond flowers and animals. Look closer, and Beth Van Hoesen just might surprise you.

Van Hoesen no longer paints or draws. Time, age and life-long chronic illnesses have conspired to rob the artist of her creative outlet, and lucidity, these days, is often fleeting. Her art and her friends now provide the back story of a complicated woman and fierce artist who would settle for nothing less than perfect, even if she was the only one to see the imperfections.

Drawing is at the core of Van Hoseon’s art – always has been. Born in Idaho in 1926, Van Hoesen started sketching as a child. The family’s orchard business failed in the Great Depression setting off a series of moves that would see Beth change schools 14 times, but through it all Beth had her sketch book for company. When she was 15 she almost died from peritonitis, and during the long recovery she had time to work on her drawing. A neighbor introduced her to oil painting, and suggested she learn by copying the masters. And that’s what she did. Step by step, Van Hoesen built her artistic foundation. Four years at Stanford, summer school at the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute) and periods in Mexico and Europe rounded out her arts education, although she found herself at odds with, or at least confused by, the artistic tidal wave of abstract expressionism that was hitting in the 1950’s. She even considered moving to New York to study with Hans Hofmann, who was considered the greatest teacher of the AE era, but a fortuitous meeting with another young artist changed her mind. Mark Adams had studied with Hofmann and promised to teach Van Hoesen everything he had learned. The tutoring soon blossomed into romance and they married in 1953 – the start of an artistic and emotional partnership that would last more than a half century.

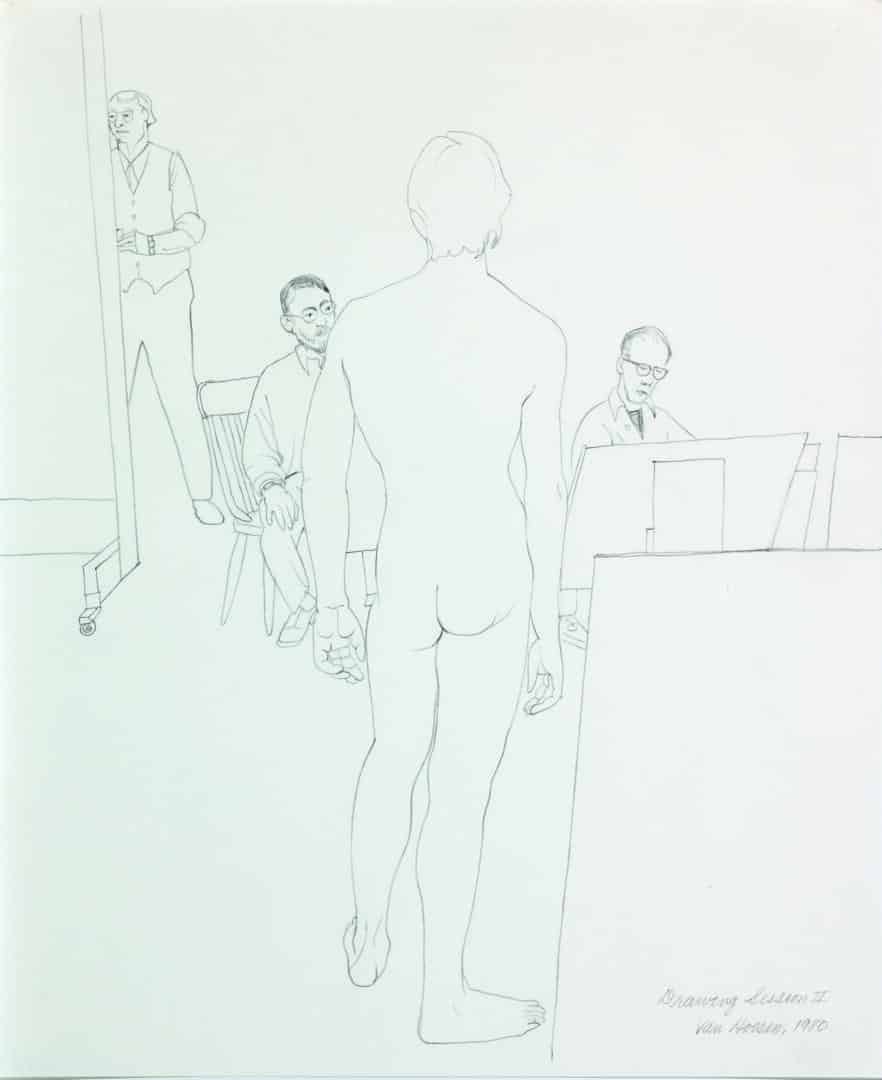

Friends say they were always a powerful presence as a couple. They traveled and studied in Europe before settling in San Francisco, where they bought and renovated an old firehouse that became their home and a gathering place for other artists. Every week for many years a group, which included such heavyweights as Theophilus Brown, Gordon Cook, Wayne Thiebaud and Paul Wonner, would get together in the firehouse for a four hour drawing session with live models. For Van Hoesen these sessions must have felt like comfort food. As fellow artist Joseph Goldyne writes, “For Van Hoesen, as for many gifted draftsmen, drawing has been akin to breathing. It is just something she has always done, what all her looking as led to, and her body of drawings alone would be more than sufficient to give her prominence in her period and among her peers.”

Goldyne knew Van Hoesen back in the day, but more as more of an acquaintance than friend. They would see each other at events but that was about the extent of it. It wasn’t until years later, when, writing a piece for an exhibition catalog, he met with Van Hoesen. It was an extensive interview that gave him new insight into the artist and woman. He says she is anything but the grandmotherly type. He uses word like fastidious and demanding to describe her approach to the work that, along with her husband, was central to her life. “Mark (Beth’s husband) was always the middle man,” says Joseph. “He softened her.”

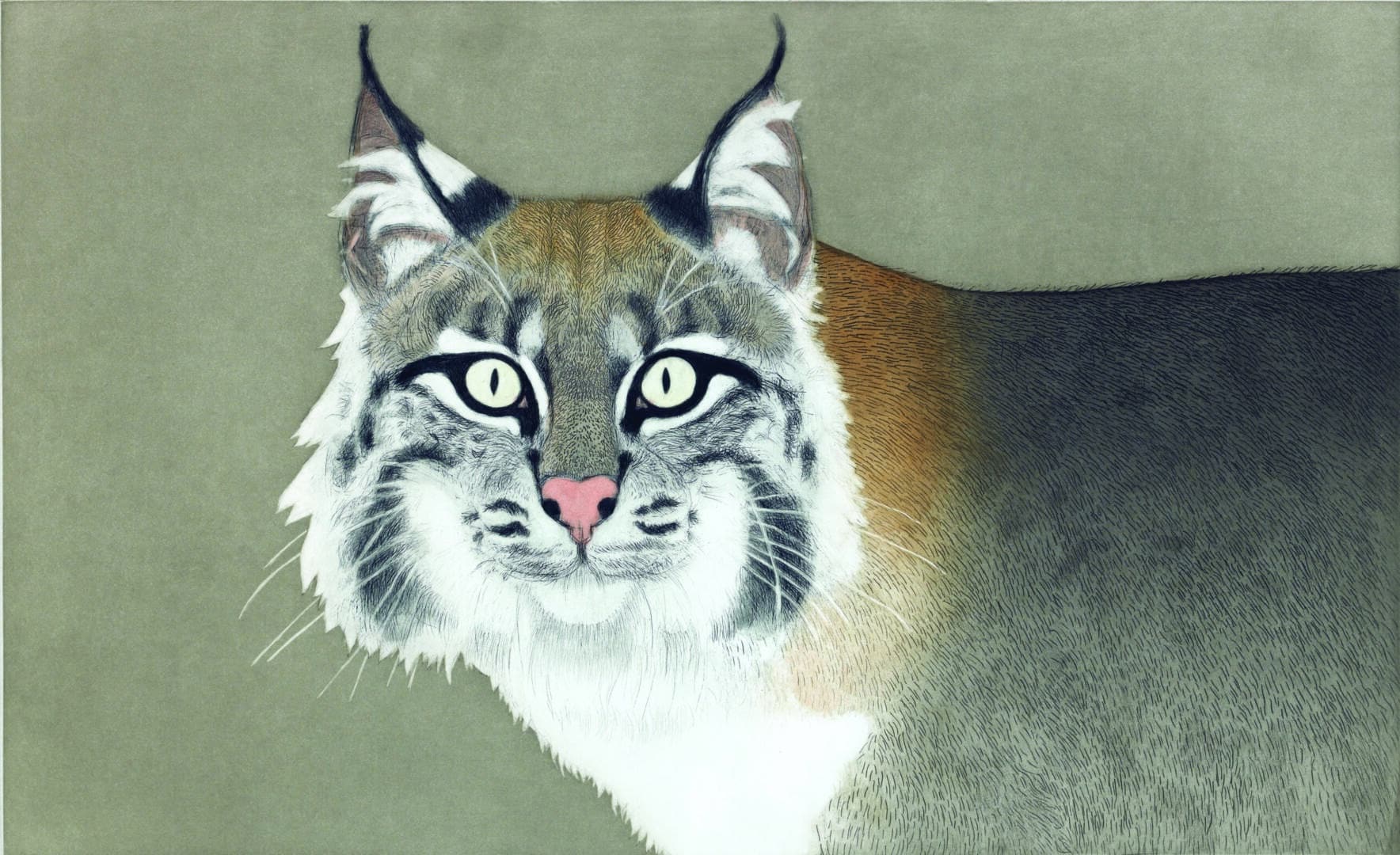

By the mid 1950’s Beth was embracing intaglio printmaking; a painstaking process that requires meticulous and detailed engraving. It meshed perfectly with Beth’s drawing sensibilities. In fact, Van Hoesen has often said it was her interest in drawing that brought her to printmaking. Intaglio is an Italian term meaning cutting below the surface and that’s exactly what it requires the artist to do. Van Hoesen would transfer a line drawing (often it would take up to fifty drawings of a particular subject before she was satisfied with “the one”) to a copper plate covered with an acid resistant black wax. The plate is then dipped into an acid bath allowing chemicals to attack the exposed copper. When the acid has eaten away at the metal to the desired depth, the plate is removed and cleaned.

Ink is then worked into the lines preparing the plate for a first pull through the press, but it is really just the beginning. Van Hoesen would sometimes use a diamond tipped tool to add detail – essentially drawing directly on the plate. Several chemical applications and steps later, and a truly remarkable talent for adding all color on one plate and Van Hoesen would have an artist’s proof – a prototype for a print run. To complete a series, Van Hoesen worked with some of the finest printers in San Francisco. With a reputation as a perfectionist, only the best could keep up.

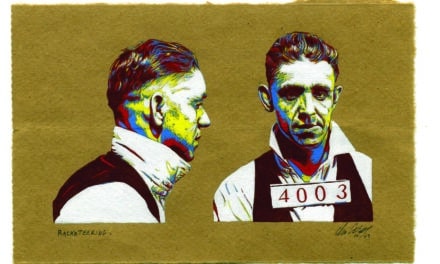

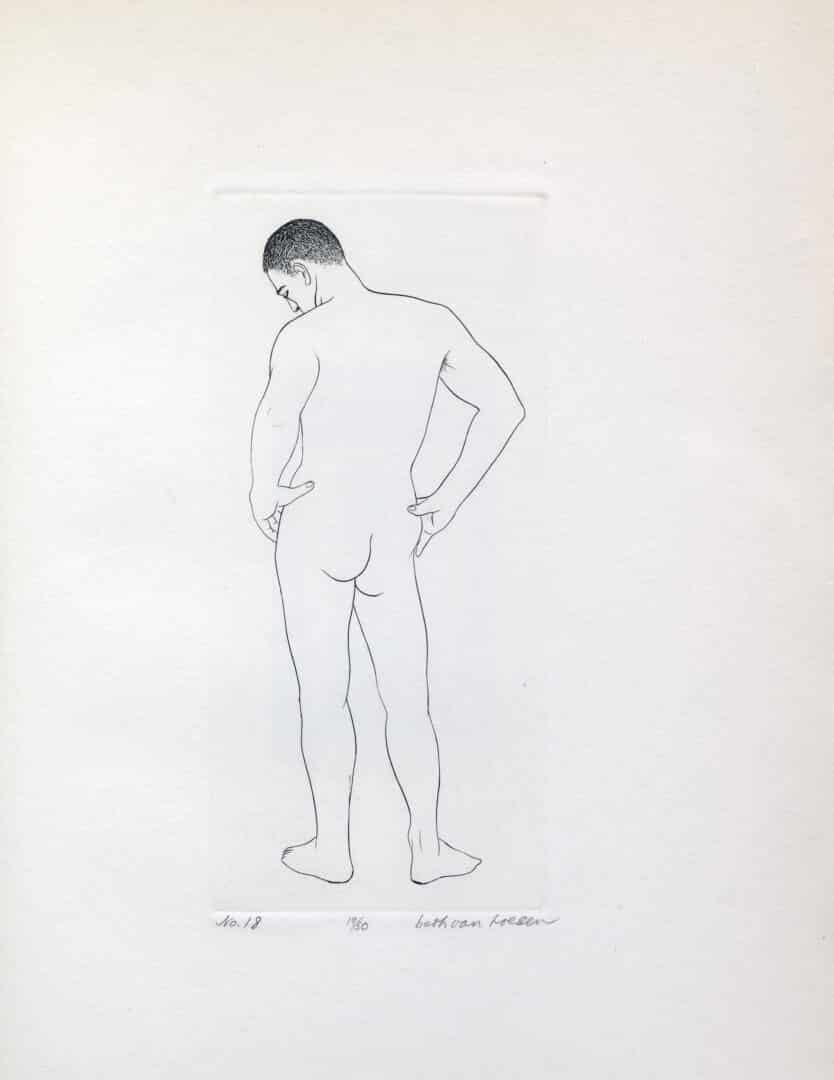

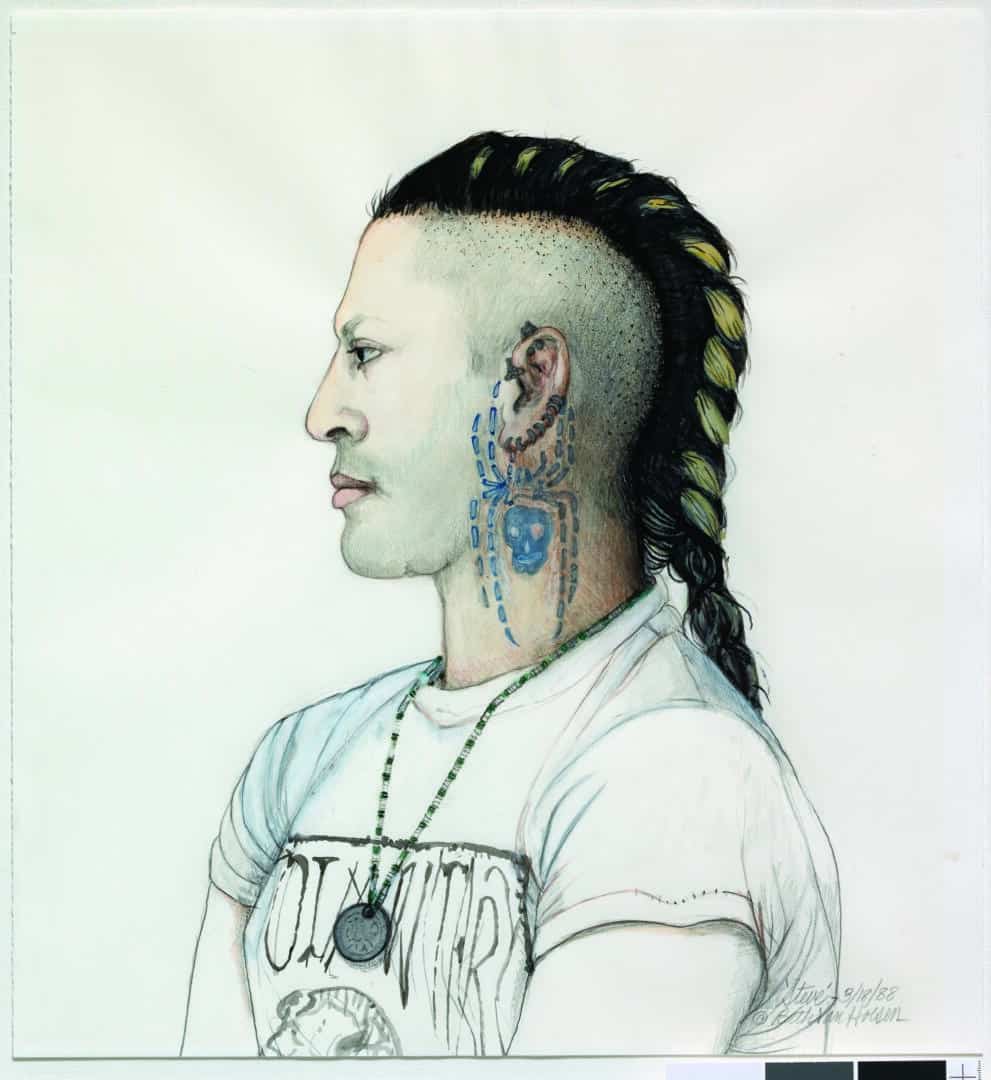

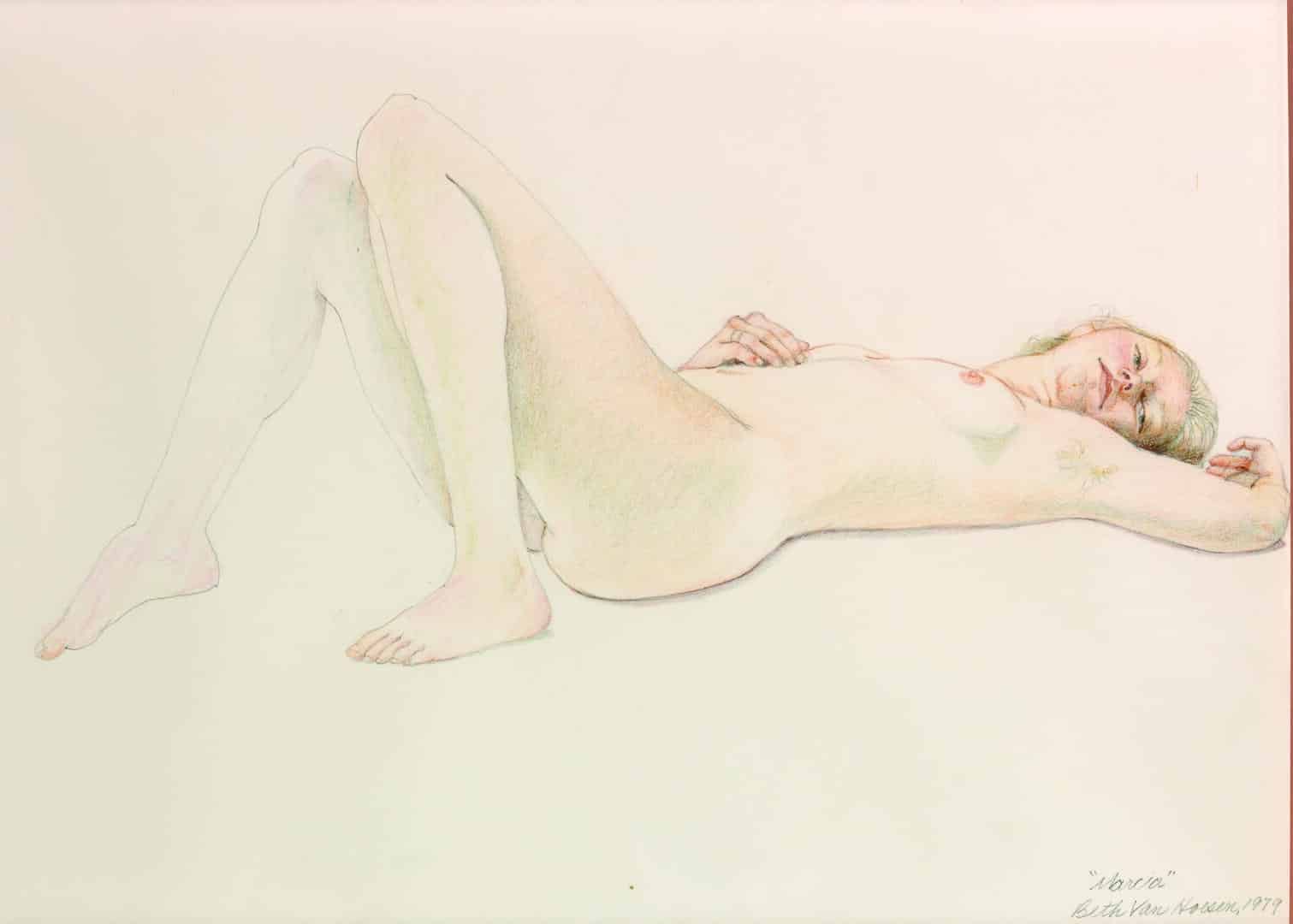

Although now known for her drawings and prints of animals and flowers, much of Van Hoesen’s early work was figurative. In 1965, she published a book comprised of 25 prints of male nudes. They are great examples of her use of line and unflinching straightforward presentation. The models are not especially beautiful, and the drawings are not provocative in a sexual way, but they are lovely. “Back,” done in 1960, is elegant in its simplicity, and what is truly remarkable about the nudes, and a series of “punk” portraits that followed, is how contemporary they feel today.“ Van Hoesen became intrigued by the punk culture taking hold in her San Francisco neighborhood in the 1980’s, and would, on any number of occasions, ask her husband “to go find” some punk rockers for her draw. Amazingly, many of the exotic creatures, adorned with tattoos and piercings, agreed to sit for Beth. Some, like “Traci’ with her multi-colored hair, alabaster skin and piercing blue eyes, became intaglio prints, while others, like “Steve” with his Mohawk to mullet and spider/skull combo tattoo, remained drawings, embellished with acrylic paint and watercolor. Van Hoesen doesn’t get a lot of attention for her figurative or portrait work, but she should. Done, for the most part, decades ago, they remain relevant, and great examples exceptional technique.

Van Hoesen’s choice of subject, whether an animal, a flower, or a punk rocker didn’t evolve. She didn’t move from one to the next in linear fashion. She continued to draw animals and flowers while working on the “Punk” series. The subject matter wasn’t as important as the process. As Goldyne writes in the catalog accompanying a Van Hoesen exhibition: “Van Hoesen’s career surprises us, though, in its understanding that radical and conservative are often shifting positions in a dance done around, rather than by, an artist. For her, the appeal of a subject owed largely to its adaptability to intaglio recording – how it would comport with her love of capturing the essence of form in line and tone.” Put simply, Van Hoesen was drawn to images that would best highlight her unique talent. For the artist it didn’t really matter whether it was feathers, fur, petals or piercings, it was all about how the image would translate as a drawing or print.

Described as feisty and some would even say difficult, Van Hoesen wasn’t the type to spend much time worrying about what others thought. Whether chronic, painful health problems, including osteoarthritis, played a role in her disposition is unclear, but it certainly affected her quality of life. As a person she is perhaps not as warm and fuzzy as some of her animal portraits might suggest, but as an artist she has always been tough and uncompromising, and deserves critical consideration as one of the Bay Area’s best in her mediums. As much as her animals and flowers dominate her portfolio and reputation, her legacy should also include her figurative work – the people she knew and drew.