BOB SCHNEIDER

Written by: BEN BAMSEY

Photography by: HOLLY BRONKO

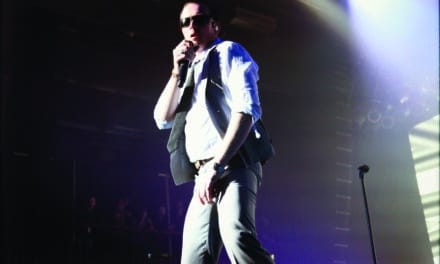

It’s Monday night in Austin, Texas. Indescribable streaks of color tear the atmosphere as the big southern sun sets. The regular crowd shuffles down South Lamar Boulevard filing into a blank looking building with a large lighted guitar attached to the roof. Outside, a 12-foot high silver suit of armor stands stoutly in front of an ordinary sign reading Saxon Pub. The buzzing, cheap neon letters above it spell out “Live Music,” shading all attempts at chivalry. Inside, the walls are covered in plywood paneling, American beers are poured from the tap and there’s a pool table in the back. The city banned public smoking on September 1st, 2005, but the place still smells a lot like it did on September 2nd. While the air is stale, the atmosphere is not. Liberal cowboys, college coeds and beer-bellied grandparents alike breathe better because of him. Their faces are as diverse as the graffiti on the bathroom walls, but their feet move in unison to his beat. Many wear his T-shirts. Everyone knows his songs. This is Bob Schneider’s stage – his home – and these people are his family, united in song.

Tickets to a Schneider show are as hot as the South Texas heat. Getting a seat is rare and sight lines suck, but the sound system is superb. And the music… the music is so brilliant that the first chord played turns this plain pub into the heaven of hearing. For the last decade, Schneider has walked in the same side door at Saxon’s promptly at 8:30 each Monday night. No green room pampering. No flashy entrance. Just Bob Schneider, his beard and his band. They plug their instruments in, sit down and jam for a couple of hours. The crowd belts out Schneider staples and eagerly awaits the new material that he brings to each show. Whether it’s a ballad or a funky beat, Bob dominates the rhythm while his voice massages the air. His silver tongue has just the right amount of rust on it – giving his sound character and distinction. The concert shifts from pretty to gritty on a dime, as Schneider’s smile fades and he spits on the stage between rhymes. He is a musician with an incredible gift of blending words and performance to provide context to the deepest feelings possible within the human condition. Bob is the Beethoven of emotion. His songs don’t comfort pain or cheer pleasure – they simply relate like nothing else can. Sometimes the message is shouted, sometimes it’s whispered – but it always echoes, “I’ve been there… now let’s do some ass shakin’ together.”

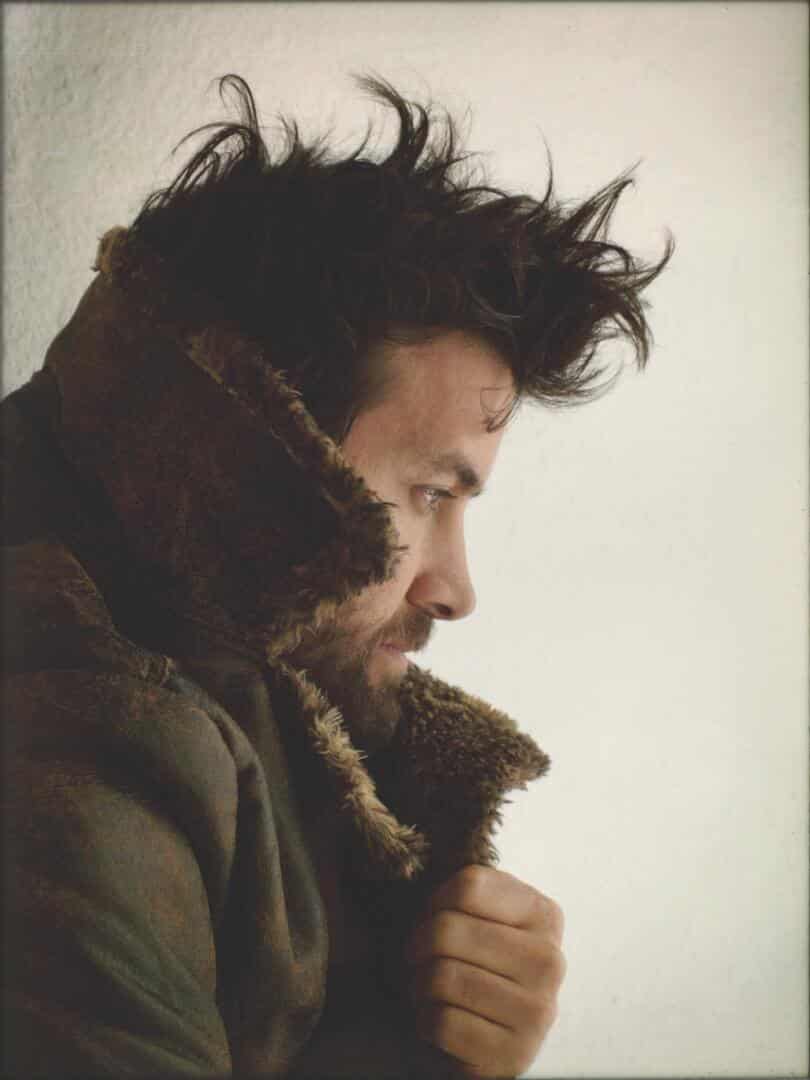

Dizzy sticks all around the music capitol of the country have been wiggling with Schneider for more than 20 years. In addition to his solo career, he fronts three of the area’s most popular bands, has won truckloads of Austin Music Awards and has the top selling album in the history of Waterloo Records. But outside of Texas, his stardom doesn’t shine quite as brightly. That’s because Schneider refuses to play by the industry’s established rules. Everything about the business side of music makes him angry. So he goes his own way. To some, that makes him a rebel – to others, he’s a reject. Regardless, Schneider has always felt misunderstood, and the plain and simple truth is that the music inside him needs to get out. Functioning without that creative fluidity would sink him, so he writes nonstop, records his albums independently and exercises his soul in front of each and every hard earned fan. Schneider is wild, engaging and frenetic on stage. His epic performances force people to feel. And that’s what keeps them coming back. He doesn’t need a record contract, a marketing blitz or a publicity-filled schedule to accomplish that.Schneider’s songs are as loyal as he is, and they cannot be compromised. They are fearless with the style-bending smoothness of a Cezanne line. Their expressions are as limitless and raw as a Basquiat mural. Schneider has turned processing the English language into an extreme sport. His pen has to be on steroids. In his young career, he has already written 1,500 songs. None sound the same. The catalog is an iPod shuffle of rhythm and rhyme that bobs and weaves through the rings of love and loss, sin and salvation. Some of the material is autobiographical; most is just storytelling at its best. All of it is soaked in a bath of uncontrolled emotion. “I can never divorce myself from how I’m feeling,” Schneider explains. “So whatever mood I’m in while I’m writing a song is going to find its way through into the music.”The color of his personality can be measured in the flair of his outfits. Schneider’s Converse All-Stars are Pepto Bismol pink – a shade they don’t make for men. So he buys the shoes red and then bleaches them. They look great with a nice suit or his signature black hoodie with the letters FAYM stretched across the chest. It’s an acronym of endearment that he coined meaning, “F— All You MFers.” Yes, Bob has a sense of humor. He’s also dated Sandra Bullock… even survived a plane crash with her. He’s Texas tough but with a warm smile and hair that belongs in a shampoo commercial. The brain beneath those locks, however, is a complicated machine that doesn’t always run at the speed of the world. Off stage, Schneider is an entirely different animal. Quiet and riddled with self-doubt, he struggles to find his place. He spends many a night wearing out the New York Times crossword app on his iPhone. Figuring out 15 across helps him fall asleep. His greatest rock star moments come when he’s solving level 5 Sudoku squares, and he still talks about figuring out the Rubik’s Cube as a kid, but games are one thing; racing with the rats is another. “Life is the most complicated puzzle of all,” Schneider says. “There’s the illusion that there is some kind of answer, which is because we want there to be an answer… But, no, there ain’t.”Creativity has been a blessing and a curse for Bob Schneider. The way he cycles concept through pen and paper into performance is pure genius… music Mensa material. But the reality that he sings about can also be crippling because when he’s unplugged from the amp, the acoustics of his surroundings don’t sound nearly as good. Like many musicians, Schneider has turned to booze and sex as an escape. But those vices got so out of control that they both landed him in rehab. “I think the problem is that I’ve never really felt very good about myself, and women – they make me feel great about myself,” he admits. “Same problem with alcohol – it allowed me to not feel so badly about me. Same thing with my work – I write songs and then I feel good about myself because I just created something. Or I can play a show and have a bunch of people tell me that they feel special and great, and then I don’t feel so bad about myself. But ultimately no amount of money or popularity will ever be enough to make me feel better about who I am as a person.”

Demons will always rattle his cage, but Bob has figured out ways to tame them. He hasn’t touched alcohol in nearly 15 years, and if he touches a woman, it’s for different reasons now. Awareness is how he copes; but music is, and always will be, his best medicine. “I really believe that it has saved me from myself, more than anything. I’ve been able to work stuff out through songs and through the writing that I would never have been able to work out any other way. I have this feeling that I have to justify my existence on the planet – so I perform, and if I do a good job, then that somehow reconciles my being here. Performing and writing are my life preserver.” He walks around in this vast sea of humanity with his eyes wide open because he can’t help it. And, thankfully, he writes about it. In the ultimate life goes on classic, “Round and Round,” Schneider sings in part, “When your head falls off your neck and hits the ground with a smack and you’re back on the wrong track… I know the time has come to get up and get out and get over this – but I don’t know how and I don’t know why.” The message: on your worst day, the cruel world still spins without concern for your feelings. The complexity of the song is insane. Schneider mixes serious subject matter with G. Love-style rapping and an opera-laced chorus. Yet somehow that conglomeration is easy to swallow.Schneider is such a prolific writer that he’s turned the process into a game. It’s more of a challenge, really, where Schneider competes against other musicians like Jason Mraz and Billy Harvey. Someone comes up with a word or phrase, and then they all have to turn it into a song. “(Schneider) can write anything and does write anything,” Mraz says about his friend. “Bob is prolificacy personified.” Nearly half the material on Schneider’s current album, Lovely Creatures, came from this game. “At first I don’t have a lot of clues about what the song is supposed to be,” he says. “But then, the more I work on it, the more it kind of reveals what it’s supposed to be and how to put it together.” For example, Schneider turned “I want my house back” into an electric guitar-based song called “Realness of Space” – a track that laments the end of the Jackson 5 and The Osmonds while dreaming of a DJ with a thousand arms. But the phrase he’s most proud of solving is “bicycle vs. car.” It’s a track that flips physical morbidity into a mid-tempo ballad about internal investigation. How would true love collide inside a human being? “Head versus heart equals bicycle versus a car,” he sings. Feeling knocks out knowledge every time. “It’s not the end of everything; it’s just the end of everything you know.”Many of his hits hint at love, a subject that hasn’t come easy in real life. The kick drum on “Changing Your Mind,” literally beats to the rhythm of a broken heart, and Schneider’s heavy voice is stained with sorrow. It’s a powerfully introspective song about the crumbling of a relationship once built from stone. “There’s a chapel in Minneapolis,” he sings, “It holds the bones of a dead saint in it, and the stain glass glows from the ceiling there. It reminds me of the feeling when I first looked into your eyes and saw the most beautiful birds fly straight into the sun with their wings on fire and the deed was done.” It’s the kind of love that gets tattooed on flesh and bones. It’s the kind of love that led Schneider down the aisle and produced a beautiful son. But when that love went away and limited the time he could spend with his boy, it created a black hole that swallowed his heart. Writing this song has helped. “What’s so funny is the way things go down,” he continues. “Like when a star dies it doesn’t make a sound. It’s just gone. And you can’t find it when you look into the sky.” There’s somber resignation in the chorus as Schneider repeats “I can’t change your mind,” over and over again.“The great thing about being a songwriter is you can turn what are really the most horrific and painful experiences of your life into songs,” he says. “The consolation prize for being a screw up, I guess.” While Schneider’s sad side is evident, he’s also tasted love’s sweetness, and the songs that were born out of sugar are some of his best. “My two favorite are probably ‘The World Exploded Into Love’ and ‘Love is Everywhere,’” he says. “There’s something about the point of view in both of those songs that I really love and makes me very happy that I wrote them.” Most of us stutter trying to describe the feeling of holding the woman we love, but Bob found words that could turn Hallmark cards into toilet paper: “You’re the color of the colored part of the ‘Wizard of Oz’ movie,” he sings. “And we’re like Romeo and Juliet. We’re like 40 dogs, cigarettes. We’re like good times that haven’t happened yet – but will. I can tell you where we’re gonna be when the whole world falls into the sea… we’ll be living ever after, happily.” Guitars and drums serenade each other on “40 Dogs (Romeo & Juliet).” It’s one of Schneider’s most pop-sounding songs. But he truly is a musical magician that can pull any dazzling sound out of his hat. Country, reggae, rock, bluegrass, funk, electronica, mamba – any style imaginable fits his delivery perfectly. “I really don’t try and get in the way of whatever the song is supposed to do,” Schneider explains. “My ear gets tired if I hear the same sort of song over and over again. I like going from a singer/songwriter song to a jazz song to a heavy metal song. It’s more of an adventure that way. I guess I have musical A.D.D. or something.”

Schneider is a craftsman that has mastered all the tools. He welds everything from air organs to tongue drums, moog synthesizers, ukuleles, bazookas, accordions, cellos, clavinets, flugelhorns and much more on his records. He’s tried every recording trick in the book to get his music to sound the way he hears it. On “Big Blue Sea” he plays with distortion making it seem as though the song was sung underwater. On “Silver Butterfly” he sings a choral round with himself. On “I’m Good Now” his producer, Billy Harvey, wanted a deader, dryer sound on the vocals, so he brought in a heavy blanket from his house and covered Bob’s head as he sang the track. The blanket got the desired result and a laugh, too, after Schneider realized it didn’t smell so good and was making him sweat. “Turns out, Billy hadn’t washed that blanket, probably ever and it had seen quite a bit of ‘action’ over the years. We laughed about that for about a week after we realized how gross it was.” It’s a great example of Schneider’s commitment to experimentation. He is a workaholic and a perfectionist in the recording studio. It’s the reason crazy concepts turn into deeply important music that just feels right. “My favorite bands have always been Queen, The Beatles or Prince – people that took a lot of chances and were all over the map musically,” Schneider explains. “And then when I’m performing I really like the art of juxtaposition, not just different genres of music, but also different emotional music, too – like doing a really serious song next to a silly song.”Schneider has been making music since he was potty trained. He grew up in Germany with an opera singer for a father who taught his son to play guitar and drums at the age of three. “My parents partied a lot, and they’d wake me up in the middle of the night all drunk and they’d say, ‘Come downstairs and play for these people,’” Bob recalls. When he wasn’t entertaining, he was drawing like the cartoonists that had become his heroes. “I think art was my first real coping tool,” he says. “I started drawing a lot when I was four or five, and I just loved being in control of this universe. It was one of those things where the world was scary and crazy and it didn’t make any sense. But on a piece of paper with a pencil, I could make that world any way I wanted it to be, and I had total control over it and of that feeling that I got from drawing.” Schneider even went to college to become an artist, and he still makes time to paint, draw and do etchings. In 2003, he released a book of his poetry and art called I Have Seen the World and it Looks Like This, featuring 20 years of deeply personal works.There’s nothing quite as unique as Bob Schneider’s DNA. It begins with a treble clef, and then quickly slides off any scale. His identity floats with the notes of an old guitar. It is song that has saved his soul. His resume barely fits between the borders of the country’s biggest state. Along the way, he has helped turn Austin into the Mecca of Music. Schneider created The Spanks, Joe Rockhead, Ugly Americans and the raunchiest band in town, The Scabs, known for working crowds into a sexual frenzy. He is the best songwriter in a generation with a catalog that touches as many hearts as it does genres. He plays 200 shows each year, 150 of them in Texas. But it’s Monday nights and that tiny stage tucked in the corner at Saxons that matter most. It’s like an old worn-out couch in Schneider’s living room, and one of the few spaces in this world where he finds true comfort. Each live performance brings him peace. And, unlike life, they are not fleeting. That’s because each show is recorded and made into double discs for the audience to take home – an everlasting treasure that goes both ways. “On stage is where I feel most comfortable,” he concludes. “When I’m up there I really have this feeling that I can say or do anything and it’s okay. Any thought that comes into my mind when I’m on stage is fine. Anything that I decide to do, I have permission to do because I’m on stage. Whereas in real life, I really feel like I have to evaluate everything, and figure out what the circumstances are, what the environment is like, who’s around me, and figure out who I’m supposed to be, who everybody wants me to be, and even where I’m at. Am I in Germany? Am I in America? Can I take off my clothes? Am I going to get arrested? There are just all these rules and constant regulations. Everything is crazy. Life is super scary. I don’t know what I’m doing. But when I’m on stage and entertaining – now that’s when I feel like everything is just magic.”