THE BAUHAUS EFFECT

Written By: MAX ETERNITY

This year marks the 90th Anniversary of the Bauhaus school, with a century having passed since one of its former instructors, Kandinsky, wrote that noteworthy quote in his book, “Concerning the Spiritual in Art”. In that single introductory line, Kandinsky reveals the magnanimity of the artistic forest, and the proverbial trees.

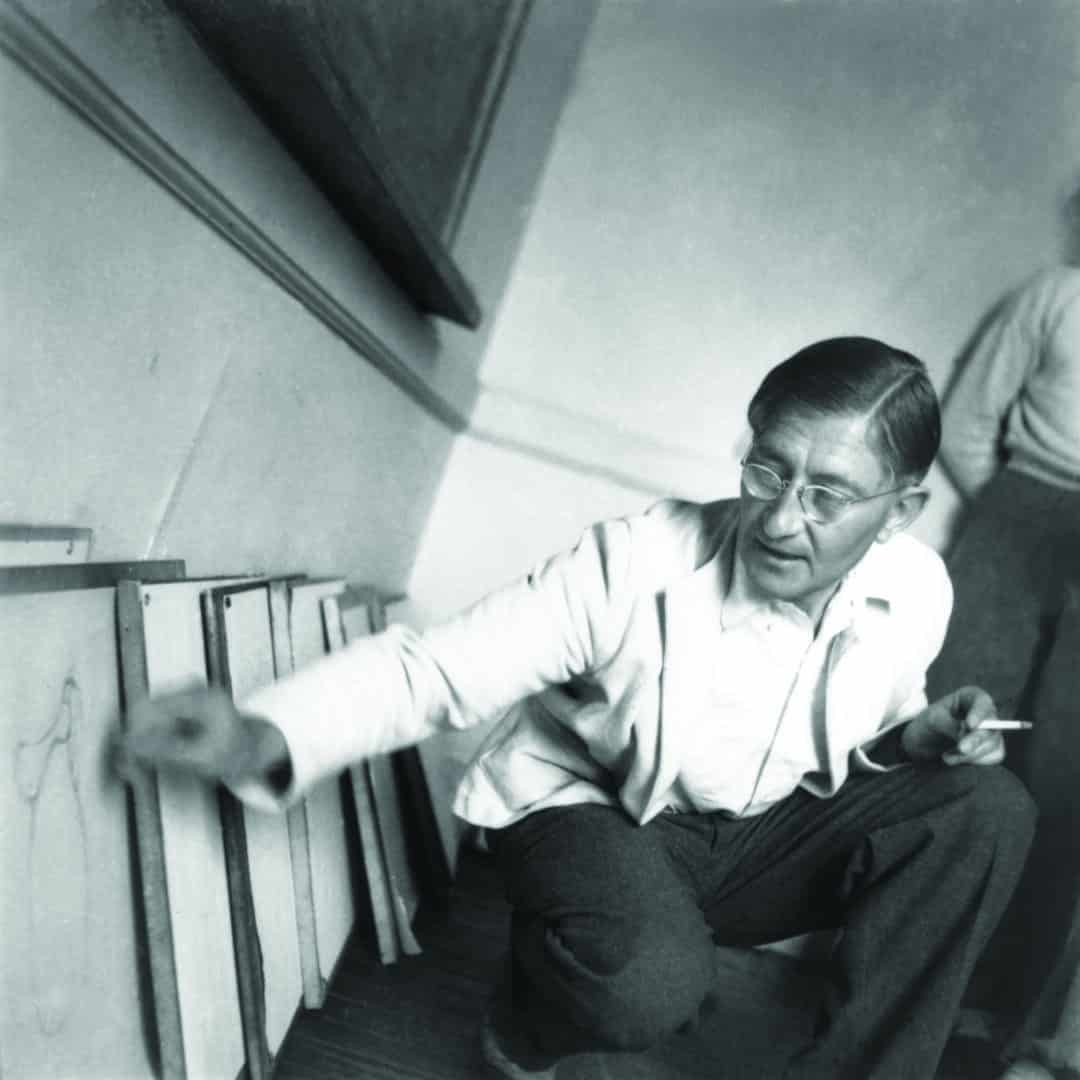

A creative zenith of the 20th Century, Kandinsky gave the world great art, great words and many brilliant ideas. So it should come as no surprise that in the decades since his passing, neither he nor the school where he once taught have yet been forgotten. And why should they be? After all, Kandinsky is one of the founding fathers of abstract art, and the German Bauhaus school is the place where the modernist aesthetic was conceived—incubated—cultivated–formed.Walter Gropius, descendent of two architects sharing the same name—father and great-uncle—Martin Gropius, founded the Bauhaus in 1919. Thereafter, with his expanding portfolio of buildings, Gropius would introduce to the world an elegant simplicity of reductive design, combining minimalistic functionality, tectonic geometry and timeless, aesthetic beauty. Several buildings would be built to house the school, though the Gropius designed Dessau site remains the most recognized of the Bauhaus’ three locales—Weimar—Dessau–Berlin.Being co-ed, another specific impact that the school had on design and education was its embrace of women. And though female students were strongly encouraged to work with fabrics and textiles, as opposed to industrial design and buildings, at various points through Bauhaus history, women would make up to 50% of the overall student body. With one of the more notable standouts being Anni Albers, who, after the Bauhaus had closed, along with her husband Josef, migrated to the US at the behest of Phillip Johnson–another towering figure of Modernism.

Mrs. Albers is in-part credited with elevating the craftsmanship of the loom to fine art status, but as Bauhaus alumni go, she is not the only woman of tremendous success and achievement. There’s also Lilly Reich, a collaborator to van der Rohe who in 1930 was the first woman at the Bauhaus to teach interior design, which included furniture design. And then there’s Marianne Brandt, a photographer who, like her male colleague Wilhelm Wagenfeld, is better known for her industrial designs of exquisitely sculpted, household objects–lamps, ashtrays, tea infusers.“The women of the Bauhaus set up a leadership structure of their own…Anni Albers and Gunta Stölzl…produced ambitious and exciting textiles that explored different permutations of design” says the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) Curator in the Department of Painting and Sculpting, Leah Dickerman. As well, Dickerman says, the women weren’t just following the lead of the men, because “the weavers rejected the idea that their work should solely be expressions of visual art.” Consequentially she says, the Bauhaus women “developed a huge range of textiles.”Yet in this celebratory year, while many rejoice that historic institution’s worldwide contributions in art and design, others are loathe to bury the memory of Early and Mid-Century Modernism deep into the obscurity of our recent past.Boston’s Mayor, Tom Menino, is on a quest to sell the city’s massive, béton brut Kallmann MiKinnell Knowles designed City Hall. In Manhattan, Edward Durell Stone’s “Popsicle” building, the Museum of Art and Design (MAD), has recently undergone a controversial make-over, disguising its original façade. There’s an ongoing brouhaha in Cleveland over what to do with the Ameritrust Tower, the only high-rise built by Marcel Breuer, who was one of the few individuals to study and teach at the Bauhaus. And in Chicago there’s a standoff over the 29-building Michael Reese Hospital campus, a site constructed through the employ of a masterplan created by Gropius himself. Sitting on prime real estate, some local government officials have chosen the site’s land for new development. Others however, are pushing back, like the Gropius in Chicago Coalition led by Grahm Balkany, an architect overseeing the robust preservation effort on the site’s behalf.

Even so, while uncertainty exists for some, it’s a different scene altogether for others. As at this very moment, while New York’s Frank Lloyd Wright designed Guggenheim Museum celebrates its own 50th anniversary, the venerated New York fixture is simultaneously displaying the largest Kandinsky exhibition to be seen in its tubular halls since the 1980’s. A few blocks away on the 6th floor of the MoMA, under the co-curatorial guidance of Dickerman and Chief Curator of Architecture, Barry Bergdoll, homage is being paid to the Bauhaus with an exhibition entitled “Bauhaus 1919-1933: Workshop for Modernity.” At MoMA, it will be the first major exhibition and presentation of the Bauhaus since 1938. But not to be outdone, in Europe, three Bauhaus institutions–the Bauhaus Archive Berlin, the Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau and the Klassik Stiftung Weimar–have come together to put forth an exhibition of truly historic proportions, featuring over 1,000 artifacts. Hosted at Martin Gropius Bau, the presentation bears the name “Bauhaus: A Conceptual Model”.Though for all the glory and glamour that the Bauhaus has wrought–for its diversity of subject matter and all the notable names associated with that place–that school–that age—that time, at this moment–in this time, all across the United States, building after building, designed by a small army of fine art masters and their intellectual offspring, now languish in the lurch; at great risk of gross neglect.Some sites even face the threat of imminent demolition.But truth-be-told, bold design and architecture in America has always been a risky game, with our former Confederacy, the Southeast, exemplifying in every way the entrenched challenges facing Bauhaus inspired, Mid-Century Modernism.

In North Carolina, Triangle Modernist Homes, a respected non-profit founded by George Smart Jr., the son of architect, George Smart Sr., reports on its website that North Carolina bears the distinction of having the 3rd largest concentration of modernist homes in America; more than New York, more than Boston, even more than San Francisco. Also in North Carolina there’s Black Mountain College (BMC), a top-tier progeny of the Bauhaus family tree. Once a school, now a museum, BMC was in its heyday, a fierce champion of all things innovative; claiming a student body, faculty and roster of guest speakers so prolific it was hard to be believe. Contributors include Joseph and Annie Albers, Jacob Lawrence, Merce Cunningham, Albert Einstein, Walter Gropius, Elaine De Kooning, Buckminster Fuller and many others. Complimenting its luminaries, the sublime lines of the BMC Studies Building—designed by Lawrence Kocher–architect and former managing editor to Architectural Record–echoes the compositional form of Villa Savoye–prior built in France by notable modernist Le Courbusier. Courbusier, who was not directly linked to the Bauhaus, did however work tete a tete with the school’s faculty and alumni, and as in life, in death, “Corbu” continues to be exalted–hailed by historians as one of the greatest designers of all time.Also in North Carolina, the North Carolina State Legislative Building was designed by MAD’s designer, Edward Durell Stone, who also collaborated on building MoMA. And another modernist hotspot in the state is North Carolina State University. Long known for its embrace of Bauhaus inspired architecture, in the 1940’s and 1950’s, under the leadership of its then Dean, Henry Kamphoefner, faculty members included James and Margaret Fitzgibbon, Mathew Norwicki, George Matsumoto, Eduardo Catalano and Charles Kahn to name a few. The roster of visiting professors was no less impressive, like van der Rohe, Gropius and Fuller, as well as Frank Lloyd Wright. Like Courbusier, Wright was not an alumni of the Bauhaus either, but he was a contemporary to Gropius; championed for his fusion of design and his hefty-plinth interpretation of Minimalism, known as the Prairie Style. One of the few modernist works by Wright in the Southeast, The Pope-Leighey House in Virginia is a prime example of Wright’s far-reaching oeuvre.Evidence of the Bauhaus influence is also observed in the Southeast’s tropical peninsula, where in Miami, Florida, the intersection of Art Deco and Modernism remains forever in vogue. And in nearby Boca Raton, Breuer’s IBM building is one of the largest, commercial, Bauhaus-derived sites to call the Orange State home.

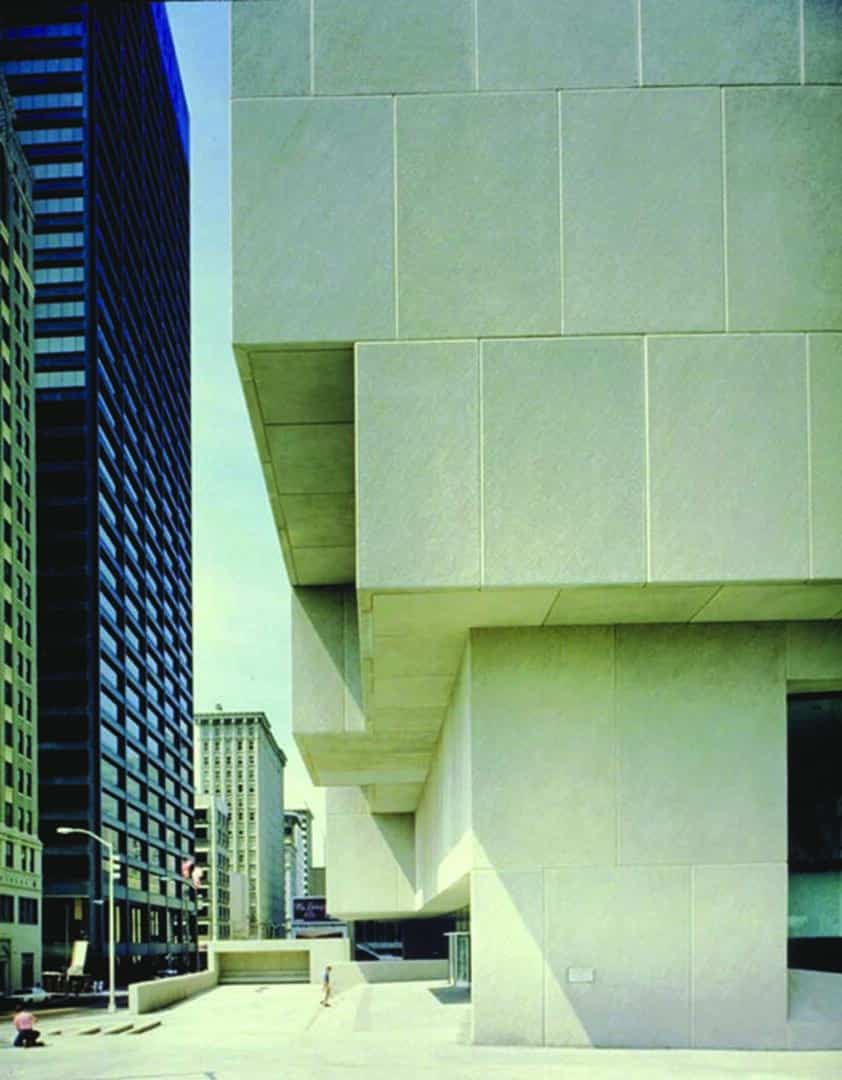

In northern Florida, time-honored modernist William Morgan, certainly carved a distinctive niche for his firm by seamlessly integrating the various sub-genres of modernism into his own unique style. Morgan, a still-living Bauhaus protégé who at one time worked for modernist architect Paul Rudolph, studied under Gropius during the early 1950’s while at Harvard. “Gropius was very inclusive in his educational process. He seemed to be able get his arms around all forms of design—respecting the authenticity in the ideas” Morgan says. And in this 90th anniversary Morgan says he believes the Bauhaus should be remembered for “its widespread influence on teaching.” Because, “the design approach to teaching, it’s the most important thing. “Due to illness, Morgan has recently retired, but one of his last creations is a tour-de-force called Sealoft. “It’s a monumental house” says Francis Lott, architect, commercial developer and co-owner of the spacious, 5,800 sq ft, beachfront residence located at Amelia Island—a key that’s part of the Southeast’s collective Sea Islands. “I’ve seen some modernist homes that are better as museums than houses, because they are too austere. But this house is very livable—enjoyable” says Lott.Georgia is another state in the region claiming an inheritance to the Bauhaus legacy. On its coastline, The City of Savannah is home to Drayton Towers. Completed in 1950 by William P. Bergen, the building represents the emergence of the latter stage of the modernist, architectural era, as Post-War Modernism morphed into the International Style. For its aesthetics and functionality, Drayton Towers served well as an advanced vision of the Bauhaus’ conceptual modality, in small part because the 12-story midrise holds the distinction of being the first apartment building in the state to have central air conditioning. The boxy mid-rise, with its linear roofline and alternating layers of white and teal windows and walls, has a calming, visual pattern that mimics the crested, aqua waves rolling upon the sandy beaches of the nearby Atlantic.Further north and inland, The City of Atlanta is the home of the Gulf Oil Building, I.M. Pei’s first independent commission–also being home to Marcel Breuer’s very last, The Atlanta-Fulton Central Public library. Pei, like Morgan and other Bauhaus decedents, did not study at the Bauhaus, instead getting his Bauhaus connection in America while studying at Harvard University, where both Breuer and Gropius had become professors after the Bauhaus was shuttered in 1933 as a result of World War II. Of Pei’s Gulf Oil building–its hard-edged, geometric, sculptural stone exterior, Thomas Little, architect and President of DOCOMOMO Georgia Chapter, says “its museum-like”. Threatened with demolition a few years back, Little says the site has since been saved, repurposed by its current owners.Notwithstanding, the same cannot be said of Breuer’s Atlanta library, a monolithic behemoth of cast concrete over steel framing that seems to defy gravity. Engineered as a cantilevered visage appearing weightlessly buoyant, the 8-story building and plaza, encompassing a full city block, has many admirers, including Dr. Isabelle Hyman, Professor Emerita at New York University, a former private secretary to Breuer and distinguished author of the centennial monograph about Breuer entitled “Marcel Breuer Architect: The Career and the Buildings.” Bergdoll’s a fan of the site too, and in being vocal about its preservation earlier this year, he declared the building a “Masterpiece” in an interview with Metropolis Magazine. However, the library definitely has its critics too, like local politician, Rob Pitts, whose successful 2008 campaign to defame the site, with an endorsement from the library’s system director, John Szabo, resulted in the building being defunded of tens of millions in revenue. Though this year Szabo seems to have broken away from Pitts, having allied himself with the Museum of Design Atlanta (MoDA) to create a 10,000 sq ft Breuer retrospective, currently on display.Still, with the future of the library unknown, it is a dilemma that begs the question: how can parties involved mutually address the converging issues of cultural heritage, progress and preservation?

“New projects are important, but part of sustainability is also preservation” says Susan Ellis-Proper, Executive Director of AIA Atlanta. “A lot of the mindset in the past has been to tear down and build new, but long-term sustainability does pay off, and as a result of a greater awareness, we’ve had to take a look at turning that mentality around.” Though, she adds a caveat saying “sustainability is not always the most economically satisfying alternative upfront.” In a similar vein, DOCOMOMO’s Little says, “We tend to think, things that are new are better. Over the last 5 or 6 years, many modernist buildings in Atlanta have been demolished on pure speculation. “So what of a new scholarship in the tradition of the former Bauhaus school? “Surprisingly, the way the school set up its structure of prominent architects and designers” meant that “they had a 14 year conversation about how art practices should be redefined in relation to post-war living and manufacturing…how to make art appropriate for its time” says Dickerman. Adding that when the Bauhaus was in operation “it was an incredible moment of technological innovation…if one thinks of the introduction of the printing press and photomechanical reproduction…it makes for a dizzying new quality about a rapidly changing society.” Adding that “the Bauhaus’ consciously grappling with these concepts–done in a spirit of questioning—created a cross pollination of great ideas.”Responding in kind, AIA’s Ellis-Proper says “I see the Bauhaus as a time of experiment—a time of creative euphoria. And I don’t know if that can be recreated now, because I don’t know if we are too jaded to allow ourselves to go there again.” Pausing in reflection, she then states firmly “There was a freedom of expression that doesn’t exist today…we are far too complex now—too critical.” Given the facts, however grim or harsh, it seems an accurate assessment. But will the future bear more hope for the inspiration of transformative design innovation?As 2009 comes to a close, the year will wrap in a burst of celebration, in praise of the many wondrous achievements of the little German art school that could.Happy Birthday Bauhaus!