A Life in Landscape

Written by Sheryl nonnenberg

Photography by randy tunnell

Richard Mayhew loves to show off the view from the balcony outside his studio. On this day, there are quiet breezes from the ocean coming over the tree-covered hills that surround his Soquel home. After years of living on the East Coast (he is a professor emeritus, Penn State University), it is clear that he has found his journey’s end. He arises each day and paints, working and re-working his “improvisational” landscapes, all while listening to the sounds of soft jazz. Although he easily talks about the past, it is clear that he does not dwell on his many accolades and achievements. At seventy-five, Richard Mayhew has accomplished more than most artists can ever aspire to, but his work is not yet done. When your inspiration comes from a deeper well, “an intense emotional and spiritual union with nature,” there is really no limit and no end.

Born in Amityville, New York in 1924, Richard Mayhew can trace descendents from both Native American and African American sources. His father was African American and Shinnecock Indian and his mother, African American and Cherokee. Although the Native American ancestry was never acknowledged (“they were treated very poorly in those days”), Mayhew credits his grandmother, Sarah Steele Mayhew, with instilling in him a love of the “nature, lore and attitudes” of indigenous people. The confluence of water, land and sky, found near his Long Island home, provided an early source of inspiration and resulted in a lifelong passion for painting the landscape. Using his father’s paints and brushes (he was a housepainter by trade), Mayhew began to explore his artistic tendencies and, by the age of seventeen, knew very definitely that he wanted to become an artist. Visits to museums in New York City only served to confirm that art would be his life’s work.

Mayhew had served as an apprentice to a medical illustrator and so, when he moved to New York in 1945, he found work drawing for children’s books, medical journals and even on porcelain dishes. He studied art history at Columbia University, and also took studio courses at the Brooklyn Museum of Art. It was a heady time in American art history, with the focus of the art world beginning to shift from Paris to New York City after the war. Mayhew studied under such luminaries as Max Beckman, Edwin Dickman and Ruben Tam. He rubbed shoulders with some of the glitterati of the Abstract Expressionist movement: Jackson Pollock (“serious and unhappy”), Willem de Kooning, who moved into the studio upstairs, and Franz Kline, who once stole Mayhew’s drink at the infamous Cedar Bar. In spite of the pressure to conform to the new, free-form style of abstract painting, Mayhew remained steadfast in his dedication to the landscape. And, amazingly, he found success; he had his first solo exhibition in 1955 at the Brooklyn Museum and another in 1957 at the Morris Gallery. He enjoyed critical praise for his intense studies of changing light and color, with critics citing his affinity with Claude Monet, Winslow Homer and Thomas Eakins.

In 1958, Mayhew was chosen to receive a scholarship to the MacDowell Art Colony, an experience that taught him the value of working collaboratively with other artists. But the award that would have the most profound influence on his work was a John Hay Whitney Fellowship that allowed him to study at the Academia in Florence for a full year. Shortly after, he received a grant from the Ford Foundation, that enabled him to continue to travel, paint and study in various European countries for the next two years. Seeing the work of great masters such as Turner (“mystical, with an unfinished quality”) and the French Impressionists propelled Mayhew into serious study of the science of optics and a desire to fully understand color theory. His paintings reflected his new understanding of color, tonal techniques and atmospheric perspective, as applied to landscape. He also experienced a feeling of pride in being an artist; in Europe, he explains, it is a noble and respected profession. Returning to the United States in 1962, at the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement, was an abrupt and cold dose of reality, especially for a black artist.

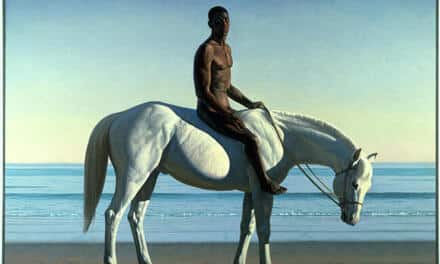

In 1963, Mayhew and several other African American artists formed the Spiral Group, whose purpose was to support and challenge each other and to find ways to express their ethnicity in the midst of the growing struggle for civil rights. Some members of the group espoused a militant approach, proposing that art should be used as a political tool. Mayhew took a more conservative approach, advising his fellow artists to “be innovative and constructive in relationship to art and your relationship with the community.” Mayhew remains skeptical of black artists who use Afrocentric imagery in their work; he feels strongly that the emotionally-charged iconography of Aunt Jemima and slave images (such as those used by Kara Walker) only serve to perpetuate racial stereotypes. He claims that he never encountered racial discrimination from his fellow artists, but that the media had a hand in fostering prejudice. Even today, he takes pride in the fact that an uninformed viewer of his work would not be able to discern his race.