metaphorically speaking

written by erin clark

Stacks of books, scarred with yellow highlighter, are scattered throughout Sam Nejati’s cluttered basement studio. In a word, phrase, or paragraph he finds inspiration – the genesis of a painting. One of his favorite authors is Gabriel Garcia Marquez. “His words are like drips on canvas,” says Sam. “Listen to this: ‘at age 30, I understood power is the attraction of a man and attraction is the power of a woman. At the age 50, I learned that for the small decisions you have to use your brain, but for big decisions you have to use your heart.’ Every line gave me an idea. What is the metaphor if I were to express it visually?” It is not just books, of course. Nejati finds his ideas just about everywhere. “It can also be nature, music or a person, but when I am painting a portrait I have to know the person because I paint the personality not the face. My work deals with what is below the surface. It deals with the prototype of a situation or a condition,” he explains. It is the translation from reality to abstraction that forms the metaphor for his life and his work.

Iranian by birth, Sam began his art training early. He attended a special art high school in Tehran where he received classical training in drawing and painting. “We used to draw eight hours a day, 150 self-portraits a week. It was like a Russian school – very tough. At the time I hated it, but now I really appreciate it because it gave me a foundation.” His uncle was a successful painter and designer – at one time he was even the official designer for the Shah of Iran. Sam has vivid memories of his uncle’s larger than life studio in Tehran. Nejati was intrigued, but it was his aunt who sparked the dream of being a real artist and coming to America. His aunt had immigrated to the United States in the 1950’s. When she would periodically return to Iran, she would bring young Sam art magazines and catalogues from various exhibitions. Sam was astonished by the art that was being created in America, and longed for the freedom to paint whatever he wanted to. It wasn’t going to happen in Iran. The current political climate in Iran was changing. President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, who served as president from 1989 to 1997 was, according to Sam, fairly supportive of the arts, but when the regime changed for the more conservative, the family decided it was time for drastic action. “Politics in general, not just Iran, but everywhere, is a very dirty business,” Sam says. “In Iran it was corrupt after the Shah left and the mullahs came to power with the promise that everything is going to be better, but after 20 years everything was opposite of what they said.” Sam’s father brought him to Los Angeles, with the thought that his mother would follow later.

L.A. was a culture shock for both father and son – too much concrete, too much traffic, too much of everything for young Sam, and even more so for his father. “My parents are both educated and they speak English, but the cultures are so different,” explains Sam. His Dad lasted only a couple of years before heading back to Iran. Despite an unstable political climate, it was home, but he left his only son to try and make his way in America. Even Sam had trouble adapting to Southern California. “When I arrived in Los Angeles, I said to myself, ‘This is not the America that I was expecting!” He had a different reaction to Northern California. His cousin, Firoozeh Dumas, the best selling author of “Funny in Farsi,” lived in Palo Alto and she invited Sam for a visit. “I got off the plane in San Francisco and said, ’Wow! This is America.’ It was beautiful.” Sam loved the climate and the people, especially the Bohemian intellectuals at Berkeley. “I love that you talk to a guy in a coffee shop who looks homeless and realize after a half hour that he has a PhD from Princeton. I love that,” Sam laughs. It wasn’t long before he had packed up his things and headed north, enrolling in art classes at San Francisco State.

Home for Sam now is a small bungalow in the Oakland hills that he shares with an 84- year-old woman originally from Germany. Her American husband died a few years back leaving her alone with the house. A fellow art student introduced the two, and it was obvious from the beginning that theirs would not be the typical landlord/tenant relationship. “She is more like a grandmother to me,” he says. “I once told her I was tired. She said to me, ‘You are only tired when you are going die.’ She remembers Berlin during World War II. So I understand.” With the house situated on a slope, the basement studio opens up to a back patio and terraced garden. It’s not fancy, but it is peaceful and offers Sam an escape when he needs a break from painting. The studio itself is messy in a painterly way – colorful tubes of paint are strewn about a large palette table, books are stacked up in columns of varying heights, a gaudy turquoise settee adorns the far wall while a painting in progress is anchored on the opposite wall. “All of my paintings start with an idea,” he says. “I get an idea, it rolls around in my head and then I pour it out onto the canvas. It is usually a metaphor.”

Nejati gets excited talking about painting, and as he does, the words tumble out, his excellent English sometimes tripped up by thoughts that move faster than his words. “Overall you understand the meaning of a book, but then you look at a page and see a series of words – ‘at his mercy’ – the words are like parts of a painting. All these pages together become a book and the book has a meaning. Every tiny thing contributes to the organization – like a musical composition. For instance, I have two paintings: Modern Love and Existence. Modern Love represents what’s going on in society. In most places you see people with headphones on and hardly talking to each other. They seem so distracted. So in my painting there are three semi-abstract figures, but they are separated. They are all listening to, metaphorically, their iPods. Existence is the opposite. It’s me trying to resist the idea of modern love. (I’m) Talking to people, trying to communicate. That is what I’m trying to say with the painting. I’m not a machine. I can use a machine, but I don’t let the machine use me.” Unlike many abstract painters, communicating the literal meaning of a painting is important to Nejati, although he has learned that he can’t control perception. “It used to piss me off when people wouldn’t ‘get it,’ but as I get older I see things differently.”

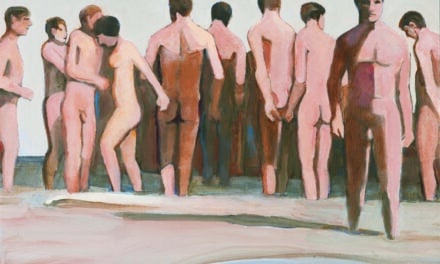

And it is perhaps a good thing that Nejati has mellowed on that point because the real power of his work is precisely that it is open to personal interpretation. Working with acrylic paint, Nejati develops layers of color, form and texture, and then using his spray bottle liberally, creates movement and mystery with streaks of color dripping across many of the canvases. Influenced heavily by the figurative training of his youth, much of his work contains the echoes of that foundation, but it is certainly not obvious. With titles like Salvation, Solitude, Epic and Existence, the artist clearly has an ambitious agenda, but there is a subtlety to the work that gives it real impact. And perhaps just as importantly, he employs good technique. His process is both intrinsic and intentional. “So many abstract painters are spontaneous,” he says, “and I am too, but there is always an idea. I start with an idea. When it goes on the canvas it changes, but I always try to pull it back to the original idea. Always – push and pull.”

Sam has been in the United States for more than a decade, and although he doesn’t rule it out entirely, he doesn’t see returning to his homeland as an option anytime soon. “If we had a good government I could see going back to Iran,” he says, “but most of my friends are fleeing the country right now, and there is good reason. Still, I’m Iranian. My teacher used to say, ‘People who forget their past, shoot bullets in their future.’ Just because I have a wife doesn’t mean I forget my mother. I live in America because of the situation in Iran, but I’m still very supportive of Iranian art and Iranian artists.”

America offers Nejati the artistic freedom he longed for as a kid, and he doesn’t take it for granted. He knows he’s been given an opportunity, and it is up to him to capitalize on it. So he spends his days and many nights – he likes working into the wee hours of the morning – trying to perfect his craft. “In the U.S.,” he says, “ you can create whatever you want, but you still have to create good things. It has to be good art and you have to be original. You have to have your own ideas and you have to have something to say.” Lucky for us, Nejati seems to have plenty to say – metaphorically speaking, of course.

BY ERIN CLARK

PHOTOGRAPHY MICHAEL YATES