The Other Stein Salon:

How Sarah Stein Brought Matisse to San Francisco

written by sheryl nonnenberg

Most people are familiar with the fabled art salons held by Gertrude and Leo Stein during the years between 1903 and 1914. In their art-filled apartment at 27 Rue de Fleurus in Paris, artists, writers, dancers and playwrights came to see and be seen. It was a hotbed for new ideas, where modernism in all areas of the arts was embraced and advanced. Gertrude Stein is generally credited with promoting the avant-garde painting of the Cubists, especially Picasso, while Leo is known for his philosophical writings about aesthetics. But there is another member of the Stein family who made a significant contribution to modern art, as a patron and collector, and whose ties can be traced to Palo Alto, California. Sarah Stein (also known as Sally) was married to Gertrude’s brother Michael and lived from 1935 until her death in 1953 in a large, rambling house on Kingsley Street. It is a little-known but important chapter in art history, when a fabulous collection of works by Henri Matisse was loved and lost; it was also a time that helped to set the future course for a major Bay Area museum, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Sarah Samuels was born in San Francisco in 1870, the daughter of a prominent attorney. She is generally described as a bright, determined woman who was the valedictorian of her high school class and who studied painting. She married Michael Stein in 1893 and they lived on O’Farrell Street. Michael was the eldest of the five Stein children and became his sibling’s guardian after the death of their parents. It was a role he would maintain throughout his life; the sensible money manager who held the reins of the family estate. Sarah and Michael had just one child, Allan, who was born in 1895. Sarah’s interest in art and her quick wit would serve her well as she was introduced to her formidable sister-in-law, Gertrude. It is said that Gertrude would thrust a book of poetry at Sarah and demand that she read it; Sarah passed the test and the two enjoyed a warm relationship, even if Sarah did not understand Gertrude’s alternative lifestyle with Alice B. Toklas. In 1903, Sarah and Michael followed Gertrude and Leo to Paris, where they established a home in a large loft apartment at 58, rue Madame. It was just around the corner from the apartment shared by Leo and Gertrude, and the four became a family unit, enjoying Parisian cafes and galleries together. It was during a visit to the notorious Paris Autumn Salon of 1905 that Sarah first encountered the work of Henri Matisse, an event that would change both of their lives.

Included in the exhibition were: Matisse, Vlaminck, Derain, Dufy, Braque and Rouault. These artists, inspired by the late work of Gauguin, Cezanne and van Gogh, sought new ways to express emotion through color. Everyday objects like trees, apples and buildings were painted in bright, almost garish color; nothing was as it appeared in real life. To the visiting public, the art was shocking and unappealing. The critic Louis Vauxcelles remarked, “Ah, a Donatello, among the Fauves (“wild beasts”). The label stuck and Fauvism, with Matisse as its leader, ushered the way for modernism in the new century. At the center of the controversial exhibition was a painting by Matisse, Woman in a Hat, which was a portrait of his wife Amelie. Bold, bright swaths of color form the background of the portrait and the sitter herself is a profusion of fantastic colors applied in large, sweeping strokes. (Ironically, it is said that Madame Matisse actually posed for the painting clad totally in black). The painting caused a sensation, with Parisians openly hostile in their reactions. But if Paris could not appreciate the revolutionary work of Matisse, the expatriate Stein family could. There is a bit of historical dispute as to which of the Steins first approached Matisse with an offer for Woman in a Hat. According to most sources, however, it is clear that Sarah Stein played a major role in convincing her brother- in- law, Leo, to make the purchase. While Leo was the acknowledged art historian and intellectual in the family, it was Sarah who fearlessly acted in a swift and decisive manner. She knew that in the art of Henri Matisse she had found a cause, and Matisse recognized in her a sensitive and kindred spirit. Matisse was quoted as saying that Sarah “had the instinct in that group.” She became his most ardent patron, critic and collector. Unlike Leo and Gertrude, who would eventually abandon Matisse in favor of Picasso, Sarah never wavered in her support and belief in Henri Matisse.

Sarah and Michael purchased Woman in a Hat from Leo (the Steins often traded art with one another) and then went on to become the artist’s major collectors. From 1905 to 1907, Sarah and Michael bought such important works as Nude Before a Screen, The Green Line, Le Bonheur de Vivre and The Gypsy. Unlike most collectors who relied upon the advice of mentors (as Isabella Stewart Gardner did with Bernard Berenson), the Michael Steins purchased art directly from the artist’s studio. Sarah and Matisse became close friends; he respected her judgment and gave the Steins the first choice of his new work. Their collection grew to include all of his major work (more than forty paintings) as well as a number of small sculptures. In addition to collecting Matisse’s work herself, Sarah became a proselytizer, encouraging all those who attended her weekly salons to feel her enchantment. While not everyone shared her enthusiasm, her efforts were pivotal in bringing the art of Henri Matisse to the attention of wealthy and influential collectors in America. As for Matisse, who was in every sense the struggling artist, the support of Sarah Stein sustained him in “my passionate years of work, turmoil and anxiety” prior to World War I.

Sarah and Michael returned to California in 1906 in order to assess the damage to their real estate investments caused by the earthquake. In her luggage, Sarah packed several paintings by Matisse and invited her San Francisco friends to view his work. Their reaction was similar to those of the Parisians. Sarah was successful, however, in enticing collectors George Of, Claribel and Etta Cone of Baltimore, and Dr. Albert Barnes of Philadelphia to buy the artist’s paintings. Upon their return to Paris six months later, Sarah was more determined than ever to surround herself with nothing but the work of Henri Matisse. The walls at 58 rue Madame were soon filled with paintings, which took center stage at the weekly salons where Sarah would lecture on the artist’s revolutionary new vision. Soon, Sarah and Michael decided that larger living quarters were in order and they began working with rising young Swiss architect Le Corbusier in planning a new home that would be built in Garches, a suburb of Paris. Called Les Terrasses, the house was a milestone of modern architecture and the largest house designed by Le Corbusier in the 1920s. It was boldly modern, with white walls, a flat façade and a ribbon of windows. The house provided a perfect backdrop for the extensive Matisse collection, although skeptical neighbors referred to it as “a box with windows.” Completed in 1927, the house was a family home and art gallery until 1935 when, frightened by the rise of Adolph Hitler, the Steins decided that it was time to return to the United States.

While Les Terasses was a bold new architectural statement, the Stein’s new home in Palo Alto was decidedly more traditional. Located on a quiet street among Victorians and Queen Annes, the Stein’s Palo Alto manse was large and welcoming, with an imposing front porch and expansive, open foyer. Sarah filled the house with her beloved Matisse paintings and Michael improved the large garden. After Michael’s death in 1938, Sarah had the companionship of her grandson, Danny, and the ever-growing numbers of visitors eager to see her art collection. Specifically, there were students and professors from Stanford University who came for informal tours and tea. According to writer Aline B. Saarinen in her seminal book on American art collectors, The Proud Possessors, Sarah would unwrap Matisse’s letters (kept in towels) and read them to her rapt audience. Dr. Jeffery Smith, Professor of Humanities and Philosophy, became a good friend to the aging collector and chronicled the history of her Matisse collection.

By 1947, Sarah was the only surviving member of the Stein family. A lonely widow, she took comfort in her grandson Danny and her beloved Matisse paintings. According to author Saarinen, Danny had a fondness for race horses and talked his grandmother into supporting his hobby, eventually buying him a ranch. Soon, the now valuable paintings (the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art held a Matisse retrospective in 1936) began to be sold. At the same time, Sarah began to suffer from what would now be called dementia, or perhaps even Alzheimer’s disease. Unscrupulous dealers preyed upon her, offering her paltry sums for the paintings. She would also “throw in” Matisse bronzes to dealers who paid reasonable prices for paintings. When her friends, collectors Harriet Levy and Mrs. Walter Haas, heard of the situation, they persuaded her to give them first choice of any paintings for sale, ensuring that she would receive a fair price. Other American collectors, such as Nathan Cummings in Chicago and the Cone sisters in Baltimore, purchased works from Sarah and, soon, much of the collection was dispersed. Sarah’s mind continued to deteriorate and in her last three years she was barely lucid. She died in 1953, her collection sold and her correspondence with Matisse destroyed.

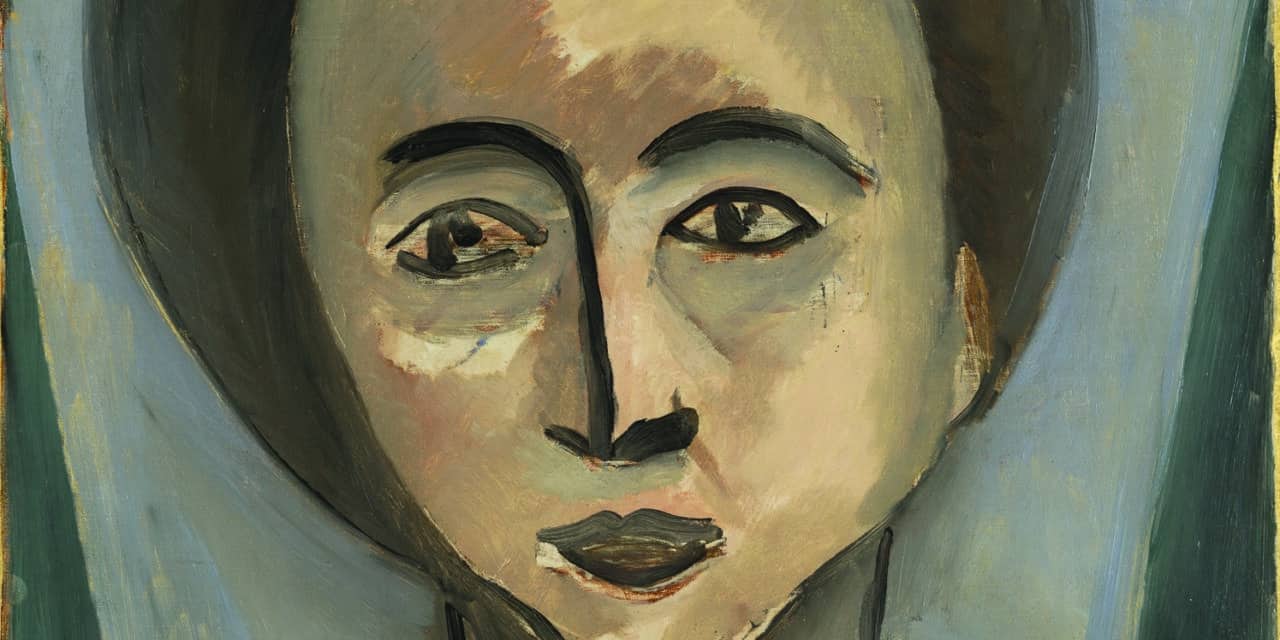

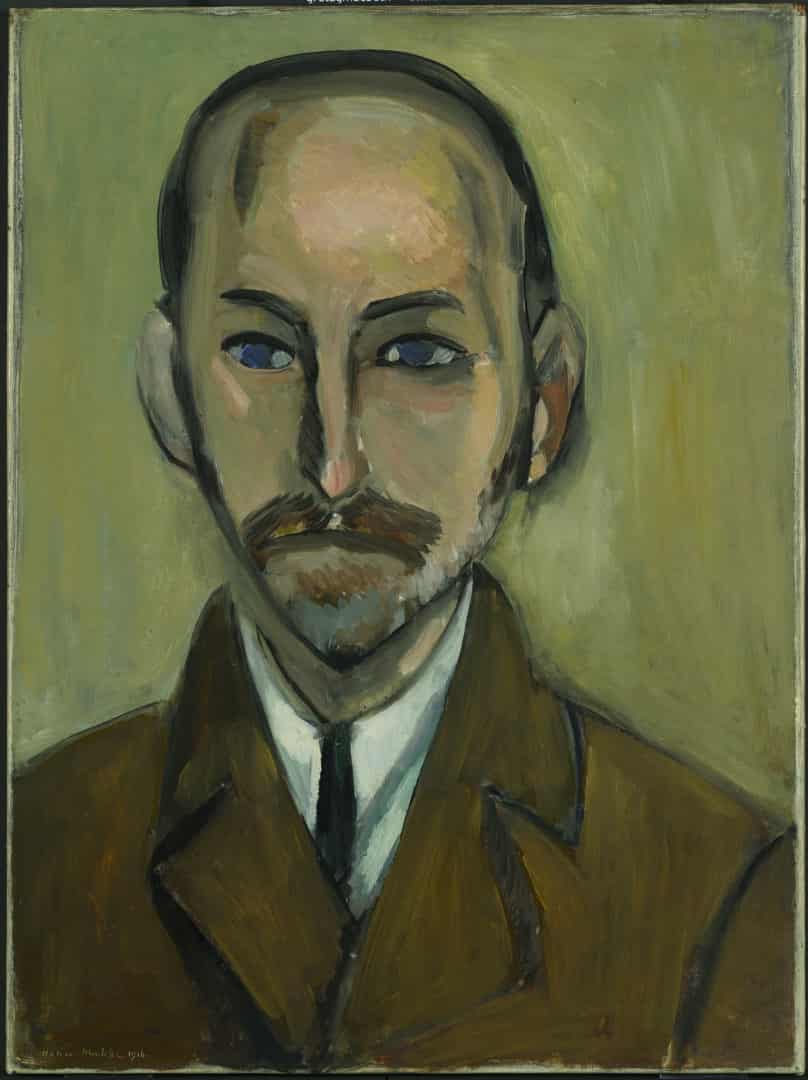

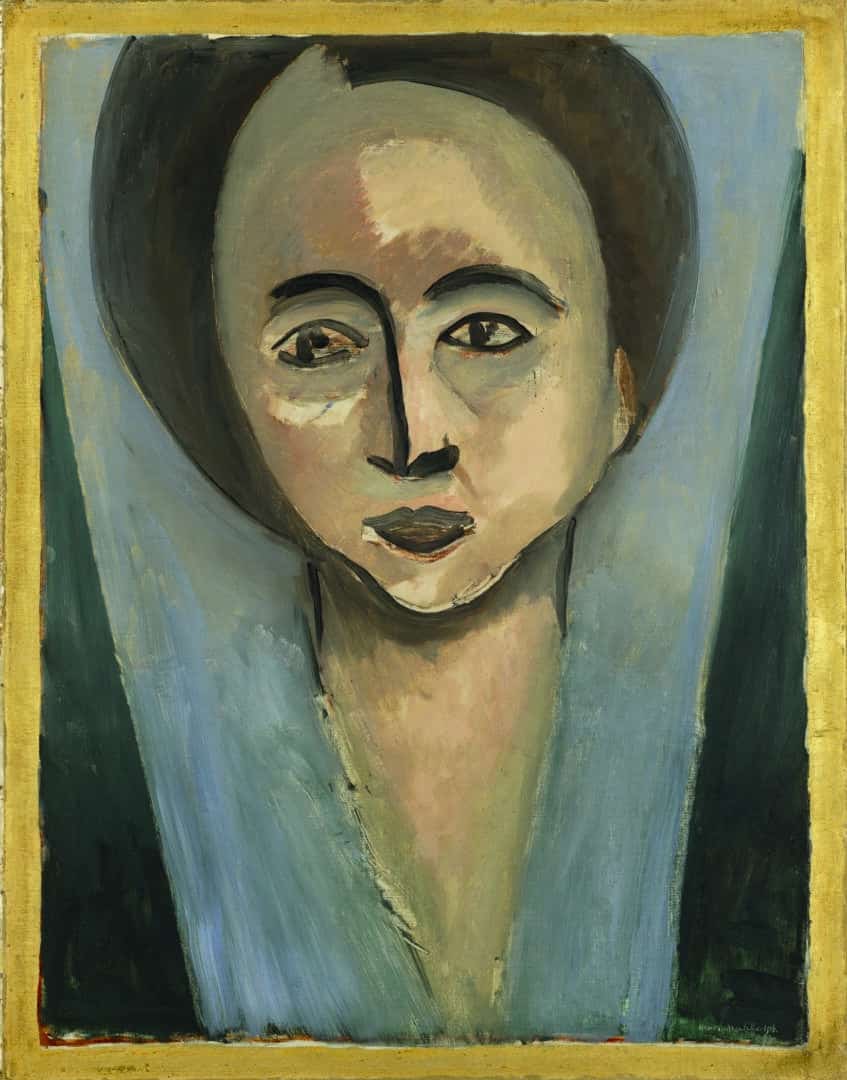

Fortunately, thanks to the efforts of Harriet Levy and Elise Haas, the contributions of Sarah and Michael Stein to the art world have not been forgotten. Haas purchased a Matisse portrait of Sarah Stein and donated it to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. She was successful in getting Nathan Cummings to do the same with a portrait of Michael. It was the beginning of the Sarah and Michael Stein Memorial Collection, still owned by the museum.

Harriet Levy, whose collection was formed with the advice of the Steins, bequeathed her own collection to SFMOMA, including the groundbreaking Woman in a Hat. Hilary Spurling, in her award-winning biography, The Unknown Matisse, notes that “thanks to Sarah Stein and her circle, San Francisco possesses unusually rich holdings of Matisse’s early experimental work.”

In 1955, SFMOMA director Grace McCann Morley wrote that “The Michael Steins…aided directly and indirectly the Museum’s growth, its public in the region and the regard for Matisse’s work and ownership of it here.” And while the Steins are both credited with finding and supporting Henri Matisse, there is no doubt that Sarah was the force behind the artist’s eventual recognition and success. She is, perhaps, the least known of the legendary Steins, but her legacy is rich and enduring.

Authors note: To commemorate its 75th anniversary in 2011, SFMOMA will present a major traveling exhibition that reunites the collections of the Stein family. The presentation will include a re-creation of Leo and Gertrude’s Paris Salon – often called the “first museum of modern art” – as well as photographs of the Steins at home and personal correspondence.

Sheryl Nonnenberg is an art researcher/writer who lives in the Bay Area.

IMAGES: Henri Matisse, Portrait de Sarah Stein (Portrait of Sarah Stein), 1916; oil on canvas; 28 1/2 x 22 1/4 inches. Collection SFMOMA, Sarah and Michael Stein Memorial Collection, gift of Elise S. Haas; © Succession H. Matisse, Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; photo: Ben Blackwell.

Henri Matisse, Portrait de Michael Stein (Portrait of Michael Stein), 1916; oil on canvas; 26 1/2 x 19 7/8 inches. Collection SFMOMA, Sarah and Michael Stein Memorial Collection, gift of Nathan Cummings; © Succession H. Matisse, Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; photo: Ben Blackwell.