STEPHAN DE Staebler

Written by ERIN Clark

Photography by Philip ringler

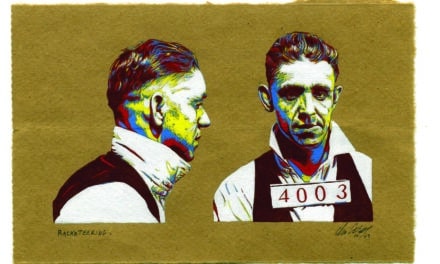

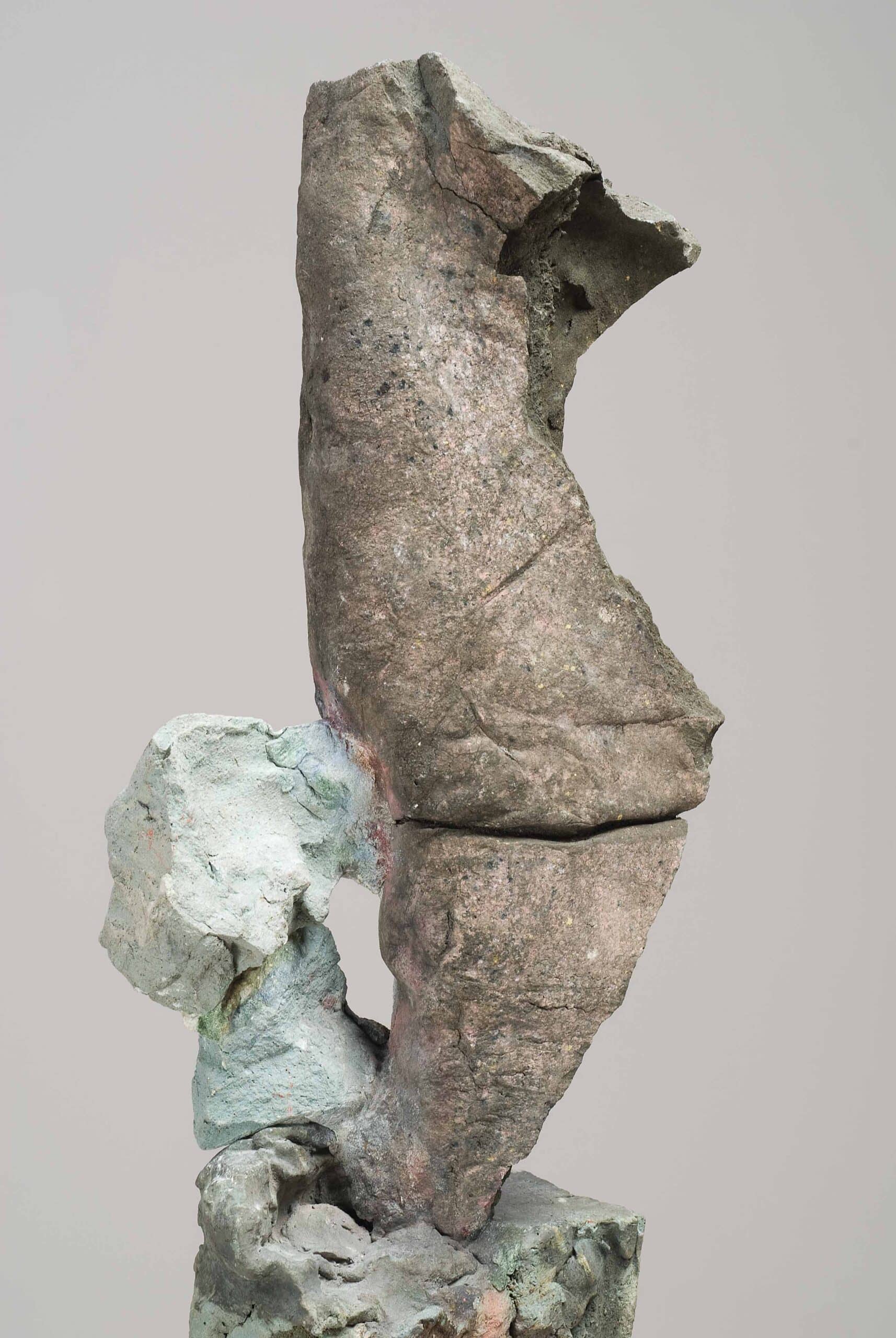

Stephen De Staebler is an artistic pack rat. He keeps EVERYTHING, from a painting done when he was eight-years-old, to his first sculpture done at about the same age, to a hard cover copy of his Princeton thesis on St. Francis of Assisi. Even things usually destined for the dump, De Staebler finds a place for in and around his home. Shattered and broken pieces of fired clay, collected over the course of 30 years, are partially embedded into the hillside behind De Staebler’s Berkley home. If the pieces of yet-to-be-used clay were placed there randomly, it does not look that way. Instead the affect is that of a sculptural rock garden – “rocks” of various and weathered patinas appear part of the natural landscape, but the hillside is much more than a graveyard for a sculptors’ remnants. These days, De Staebler is reclaiming many of the pieces and assembling them into new work. De Staebler has always been able to somehow create pieces that feel ancient and contemporary at the same time, but this new work embraces that from a personal point of view. By taking “pieces” of his past and melding them into something new, De Staebler has brought his art full circle.

“I try to keep everything. If I didn’t have that type of personality I never would have gotten to this point with my sculpture,” he says simply. Over the years, De Staebler fired hundreds and hundreds of unused clay fragments – sometimes to see how the clay would react to the kiln, sometimes to experiment with color and sometimes for reasons he didn’t even understand. “I couldn’t explain to anyone much less myself why I was doing it. It just seemed the right thing to do – firing and then saving pieces that never went anywhere. Then in the last two years I began to see the connection between fragments from yesterday and fragments from thirty years ago. There is almost a magnetic attraction between them.” Only De Staebler knows how the pieces fit together, so that the resulting sculpture is a culmination not a combination of his life’s passion – fragmented figures resurrected out of years of work. More than any other period in this artist’s long and storied career, these sculptures seem to satisfy De Staeblers’s lifelong struggle to balance the physical and spiritual sides of his nature. For most of his 76 years, De Staebler, and by extension his art, has existed somewhere in between.

“I learned more about art playing basketball than I did taking art lessons,” De Staebler says only half seriously, but still it’s an unexpected statement coming from an accomplished, well-educated artist who is only 5’2”. Although small, De Staebler made his high school varsity basketball team mainly, he says, because the coach wanted a couple of players with speed. The team was good. “Our senior year we never lost on our home court, and we would have been state champions if not for one missed shot,” Stephen remembers. “It was double overtime. High-tension basketball. I fed the ball to our best shooter, and…it didn’t go in. I still think about what might have happened if I took the shot. It’s just a fantasy, but the ‘what if’ is still with me.” Stephen calls basketball one of the great experiences of his life, and it taught him something profound. For the first time in his life he became aware of filling “space with his body.” “When you play basketball you have to get into a space and rhythm, much like a dancer,” he says. He would later transfer that physicality to his art by literally swinging from the studio rafters to get a better view of large undulating floor pieces, jumping on the clay, throwing his body into it, and even leaping from the second floor of the studio into a reclining figure to create an “incredible” pelvic area. When he built his Berkeley studio a few years later he even added a nine-foot high balcony just for such leaps of faith. “Physicality transfers from the artist to the piece. When you are working with a certain scale, the human body can be a good tool,” he says simply.

De Staebler was born in the heart of basketball country – Saint Louis, Missouri – in 1933. He showed early artistic promise, sculpting his first figure at the age of eight and painting canvases that even De Staebler admits were “pretty good” for a kid. “When I was about eight years old I was not allowed to leave the dining room table until I was finished, which is painful for a child. So I would fill my time by reaching out and shaping the butter cube. It’s actually close to clay in texture. I’ve been tempted to try it out later in life,” he laughs. His father wasn’t so amused at the dinner table, often telling young Stephen to “stop fondling the butter,” but overall the family was supportive of Stephen’s artistic tendencies. Gus Ludwig, a family friend and faculty member in the art department at nearby Washington University, bought Stephen a child’s easel and his first set of real oil paint, and the two would set up on the lawn and paint together. The experience left a lasting impression, and Gus would also be there at another of De Staebler’s artistic crossroads later in life. For as much as Stephen liked art and was good at it, he was ambivalent about pursuing it as a career. “If anything, I had the opposite experience of most people who become artists,” he says. “I wasn’t sure what I wanted to be, but my parents wanted me to be an artist.”

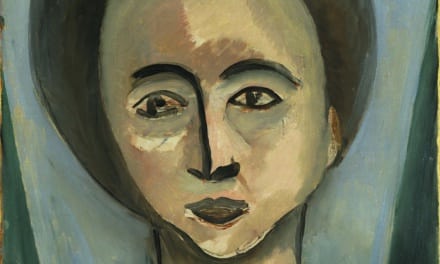

De Staebler went to Princeton looking for a good liberal arts education and planned on doing his art on the side. The academic requirements were challenging, but it proved to be an enlightening time for Stephen. He recalls one experience his freshman year: “I was standing at the window of my dorm watching an intersection below – all the traffic and all the students. And then with amazing clarity I came to the realization that I was watching the cars and the students intersect, forming a perfect cross. It was a symbolic experience for me. I think what gave me peace of mind was the realization that you can exist on two planes – the plane of accomplishment and the plane of the spirit.” That epiphany would guide Stephen for the rest of his life, and the cross would become a recurring symbol in his work. He majored in Theology at Princeton, but art was always in his peripheral vision. During one summer break, De Staebler attended seminars at the renowned art school, Black Mountain College, where he studied with two artistic giants: Ben Shahn and Robert Motherwell.

Stephen came with an agenda. He had just spent a few weeks with his uncle on Long Island and became intrigued with the subway. “ I rode every subway train. I was fascinated by these underground places. So when I got to Black Mountain College I didn’t paint the beautiful landscape. I was making pictures of the subways. Shahn didn’t teach groups, he just made himself available to students. He thought the subway drawings were interesting but wanted to know ‘when I was going to paint a painting?’” De Staebler rose to the challenge and loved the one-on-one go-at-your-own-pace teaching style. The second session with Motherwell was a whole different experience. As a leading voice of the Abstract Expressionist Movement and a member of the New York School, Motherwell wanted his young students to take the plunge into the abstract. De Staebler couldn’t do it. He was floundering. He knew it and so did his teacher. Motherwell invited Stephen over to his cottage for a drink before dinner. De Staebler was initially flattered, but that euphoric feeling didn’t last. Over martinis, Motherwell dropped a bombshell by saying, “Steve, I’ve noticed you are really good with children. Have you ever considered a career in recreation?” Slightly tipsy from the cocktail, Stephen didn’t realize what Motherwell was actually saying until he got back to his room. Boiling mad over the insult, he packed his bags on the spot and caught the next Greyhound bus out of town.

At this point in re-telling a story that has been told many times, Stephen stops and rubs his forehead. “ Sometimes I question the veracity of my own story,” he says. “I’m not sure I left for the reasons I thought I did.” Stephen headed for his family’s farm in Southern Indiana, where he hooked up again with his childhood mentor Gus Ludwig. The two shared an overwhelming sadness – Gus from the devastating things he experienced as an infantryman in World War II, and Stephen from the loss of his mother who was killed in a plane crash months earlier. Her death affected Stephen more deeply than he knew. Therapy for both came in the form of a boat. From scratch the two built a canoe.

“I think I got closer to myself by building a boat than painting a painting,” he says. “It was really my first step toward sculpture. Sometimes success is the wrong thing.” Motherwell never knew it, but his rejection sent Stephen on a path toward his true identity as an artist. To this day, the canoe hangs from the rafters in De Staebler’s studio.

De Staebler fell in love with ceramics while doing graduate work at UC Berkeley in the late 1950’s. Stephen headed to the Bay Area after a stint in the army and teaching at a small private school in Southern California. He wanted to get a teaching degree so he wouldn’t be “at the mercy of private school tightfistedness.” He thought he would teach and be an artist on the side. As it turned out, it was the other way around, thanks in large part to the influence of Peter Voulkos – a groundbreaking sculptor who came to Berkeley in 1959 to establish the ceramics department. “He was so charismatic. You picked up ideas without even knowing it. It seemed to happen almost by osmosis,” Stephen says still clearly in awe of his mentor even after all this years. “At the time, I was thinking of applying for a Fulbright Scholarship. I had it in my mind that if I wanted to be a serious artist I needed to go to Europe and work with a master sculptor, but I’d hardly done any sculpture. The Fulbright was looking for a bigger body of work,” he laughs. “So I didn’t get the situation I wanted, but it turned out I already had it. It was a great irony. I was so set on getting to Europe, and instead I walk across the hall and there he is.”

At the time, ceramics was still thought of more as craft than fine art, but Voulkos was one of the artists who blew that concept out of the water. Stephen quickly became a disciple. “I remember the huge mounds of clay,” he says. “I took a cutting wire and sliced off an enormous hunk. It was all I could do to lift it. I staggered over to my work area. And I worked for two weeks without any exchange with Voulkos – no instruction, nothing. But I was working like a beaver. He finally did come over one afternoon and looked at this piece of clay that I was shaping into a big bird, and Voulkos says, ‘what is that? Is that a turkey?’ It was a turkey – stylized – but still a turkey. It was a liberating experience because I learned I didn’t need him to advance. I just needed space to do it.” And De Staebler took full advantage of the opportunity, experimenting and learning about the clay. Mistakes became his greatest learning tool. He was committed to clay-only sculpture – no artificial armature to give structure to the piece. It was a noble idea, but gravity foiled some of his greatest ideas, until he stopped fighting and learned to work with it. A breakthrough moment came one day when Stephen was applying slabs to a clay column. The slabs began to slip unevenly down the column, forming undulations of clay, which to Stephen’s eye made the piece look like a large ceramic landscape. Stephen was excited. “I found a way of working with clay that let me say I won. There really is no tradition of landscape in sculpture, so I really felt I was charting new ground, and that was good.” Voulkos thought so, too. In a letter of recommendation written after graduation, Voulkos said Stephen was doing original work. For any artist, but especially a student, that is high praise.

Stephen worked with the landscapes for the next ten years, while simultaneously developing his figurative work. It was a decade of discovery. “It was an attempt on my part to establish a connection with the earth and the imagery that comes about when you use clay to express the figure,” he says. “Instead of trying to turn it into something non-clay like, I try to guide the imagery to that world where the touching of clay is everything. You measure what you are doing by how completely the image gives breath to clay in the figural form. It’s a no man’s land when you start thinking about it. Ceramics is not involved in that generally. I kept at it for about ten years before I broke ground that felt right.”

De Staebler’s love affair with clay was not without the occasional transgression. “I thought I would work with clay forever and I stated it publicly. Then I started working with bronze,” he says, as if admitting to some sort of infidelity rather that simple experimentation with a new material. “I was looking for a way of dealing with gravity that clay alone didn’t offer, but rather than give in to armature solutions, I made that pact with myself that I wouldn’t use any material other than the clay itself as an armature. During that struggle I was converting some of these forms into bronze. I never regretted jumping away from clay and going to bronze, but I always come back to clay.”

During this period, De Staebler moved to the Berkeley Hills, and with the help of his graduate students – he was teaching at San Francisco State University – he built his house and studio, and like his sculptures his “touch” is evident everywhere. From the irregular ceramic tiles in the kitchen, to the step stones down to the koi pond, to the sculpture standing silently around the pool, to the actual studio and house structures – De Staebler and his crew did it all. “I’m very hands on,” Stephen says. That could be the understatement of the century for this artist, and perhaps the four words that describe him best. His touch with clay is what sets him apart. Sometimes it is a gentle caress, and sometimes it is a body blow, but his manipulation of the clay is unique to his hands, and his heart.

Much has been written about De Staebler’s sculpture and its perceived connection to archeology. Many of his pieces do seem in various points of discovery, as if they’ve just been unearthed and are emerging from the land, or have just been pulled from the ground in different stages of decay. The connection seems obvious, but the emotional impact goes far beyond the scientific. There is, if not sadness, then certainly poignancy to the work that gives it a raw emotional depth that speaks to the finite nature of all things. The figures are not pretty in a traditional sense, or even whole, but that’s the point. De Staebler let go of “perfect” long ago. Even his angels are often minus one wing, as if even the divine can do only so much. He admits the angels had a lot to do with losing his mother in a tragic accident – his way of trying to connect with that, which is lost. And that is the power of De Staebler’s work. It is personal and universal at the same time. Like the human condition, fragments, cracks and distortions are part of the package.

No, it is not perfect or pretty, but it is beautiful.