abandon the plan

written by erin clark

photography michael yates

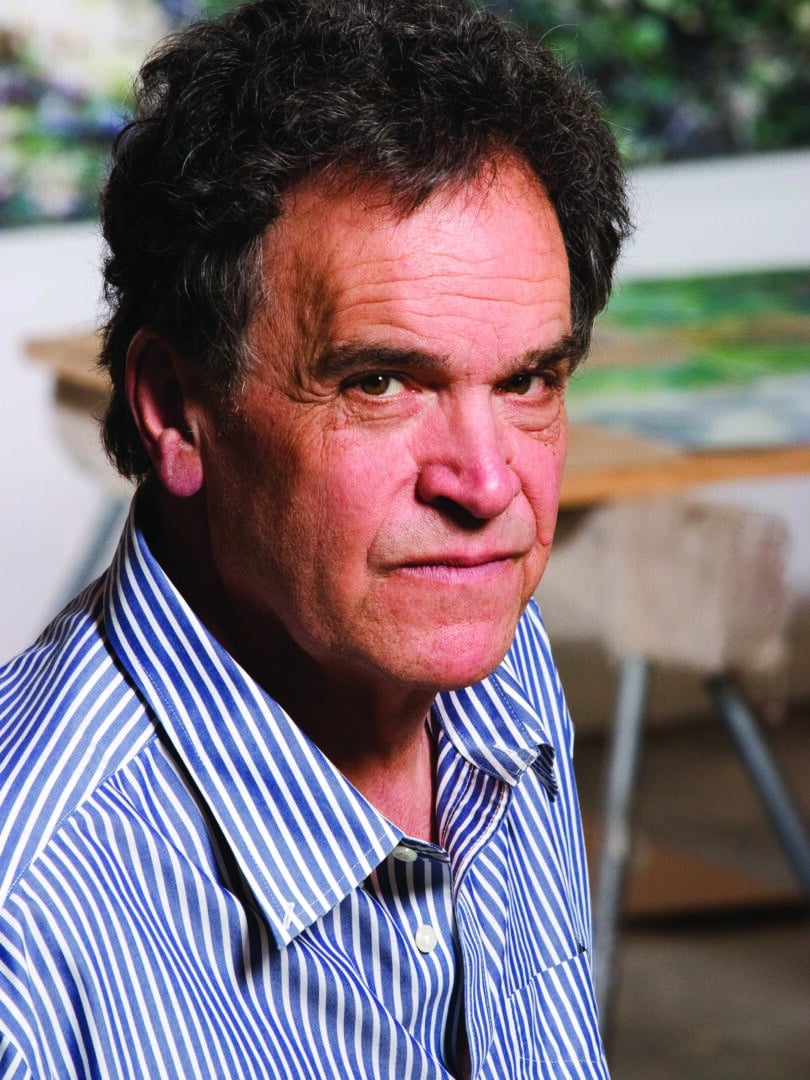

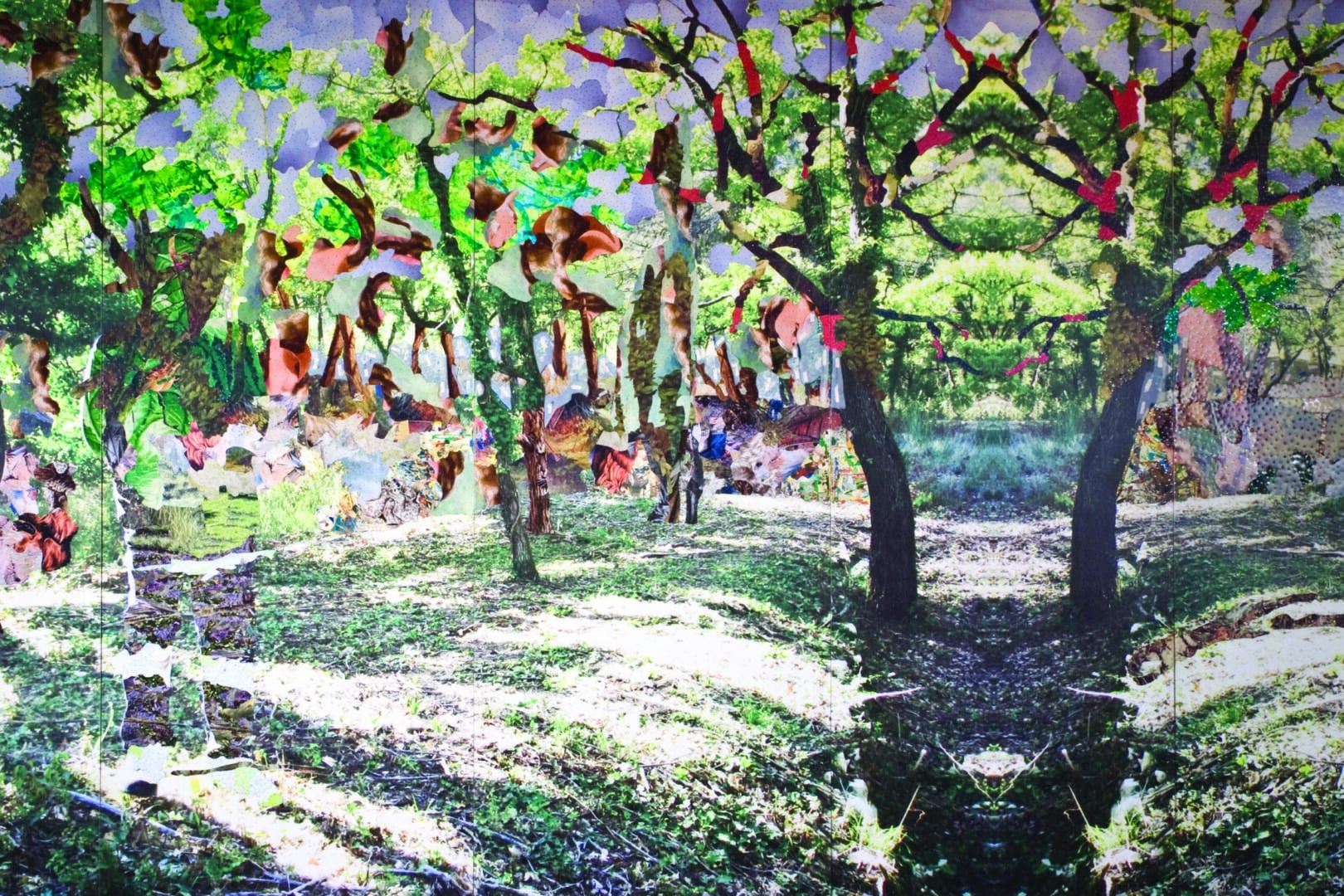

For artists, this is hallowed ground. Aix-en-Provence, just north of the famed French Riviera, is the birthplace and old stomping grounds of Paul Cezanne, the man many consider the father of contemporary painting – the artist who provided the bridge between 19th century impressionism and 20th century cubism. Many artists talk about Cezanne with a rare reverence, so to walk where he walked, to see what he saw and what he painted in his beloved hometown, is something on the bucket list of many artists. That L.A. artist Tony Berlant found inspiration in this artistically sacred place is probably not all that surprising, but it wasn’t planned. He did not go to Aix-en-Provence looking for ideas. An artistic collaboration with his long time friend and colleague, famed architect Frank Gehry, brought him to southern France. From the Chateau La Coste to the terraced landscape intersected by ancient stonewalls, Tony was instantly enthralled with the place and the history, and honored to be part of a project that would only solidify the region as an art destination. As always, Tony chronicled his journey with photographs, and through those found the basis for a new body of work. Tony has worked with and from photographs for a long time, but this new series is different in that he is leaving some of the original image exposed, giving the work a depth and dimensionality that seems fitting for the place. It wasn’t what Tony expected to get out the trip, but then again he has always said he does his best work when he abandons the plan. “I used to have a sign in the studio to remind myself,” he laughs. These days he needs no reminders.

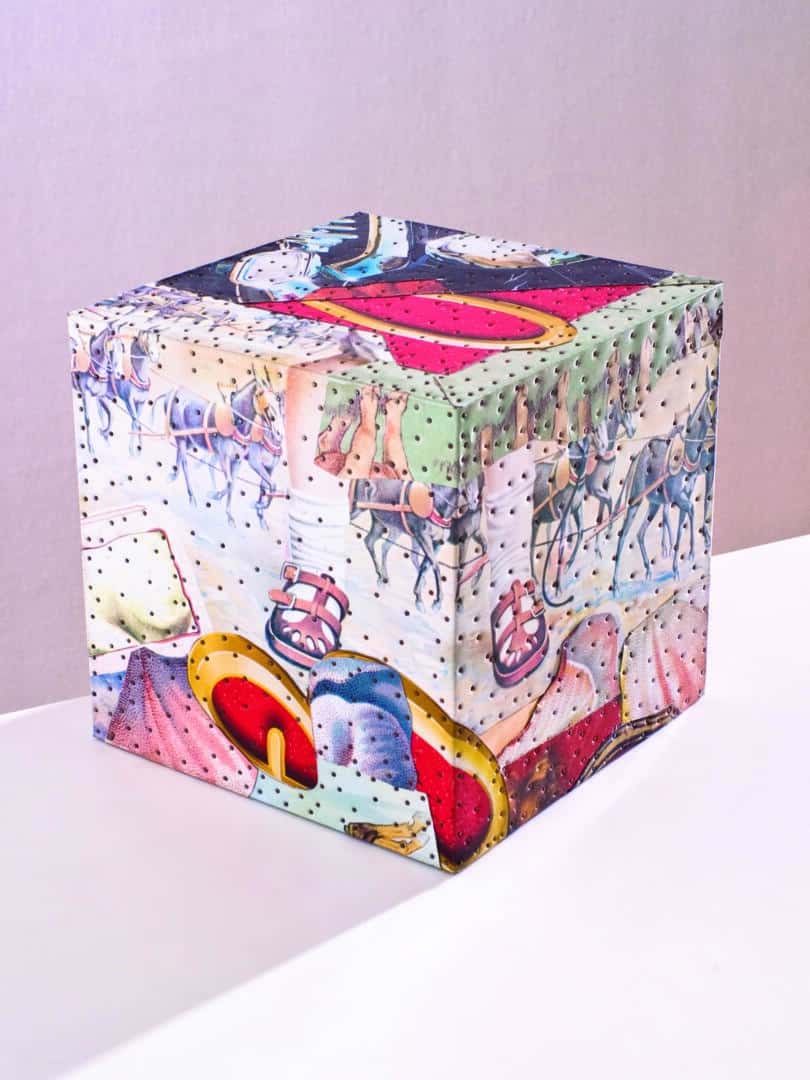

The studio is made up of several large rooms on the lower level of the home in Santa Monica that Tony shares with his wife. The upstairs living area is a lovely mix of minimalism and remnants of a life well-lived; stacks of books, newspapers, magazines, a six pack of wine bottles tucked next to the counter in the well stocked kitchen help paint a picture of the home’s routine. And the sun-drenched patio, a nod to the Southern California lifestyle, is encased by the vivid color of the passionflower – seemingly one continuous vine weaving itself into an organic tapestry surrounding the outdoor space in a shock of color that seems appropriate for this artist. A dedicated collector as well as artist, Berlant’s walls are filled with names like de Kooning, Ruscha, ________and, of course, more than a few Berlant originals. In the living room, a “funkadelic” sculpture is a focal point in the sparse-by-design living room. Made out of plastic and broken dishes Tony says it represents an atomic explosion. “Part of a series I showed in Houston in 1973,” he remembers without hesitation. Over the fireplace is one of Tony’s more recent metal collage assemblages. “My way of making things used to be big elaborate drawings that I would cover with tin,” he says, “but as a result of tendonitis, I started taking photographs.” For years, the photographs would disappear completely, covered over by colorful pieces of tin cut from mostly nostalgic advertising material, and then arranged over the image to form something of elaborate, artistic puzzle, and finally attached with steel brads, giving the final piece an over all dimpled complexion that is both old- fashioned in craftsmanship, and futuristic in a Mad Max kind of aesthetic.

Tony started using tin back in the late 1950’s. Heavily influenced by artists like Robert Rauschenberg and Joseph Cornell, Berlant was intrigued by the use of non-traditional materials. They would find a material and make it their own as if they were inventing their own art tradition. I liked that,” he says. Serendipity intervened, too, when Unger’s Market, across the street from his studio, went out business. Before demolition crews moved in to tear down the building, Tony recovered a pile of old tin signs. At the time he just liked the way they looked, but he soon found a way to incorporate the material into his own work. “It’s great when an artist can find the material that is the magical passport into themselves,” he says. For Tony Berlant, tin provides the magic, and he admits that much of the imagery he uses has some kind of personal meaning. He picks up a piece of metal showing the likeness of Lucille Ball. He often uses her signature fire engine red hair – cut up there is no way to identify Lucy, but he likes the color and he likes the personal memories of the woman. “She used to spend a lot of time in Palm Springs, and our family used to spend a lot of time there, too. Back then movie stars felt they had to be nice to their fans, and they weren’t afraid of people so I got to meet her. I never met Marilyn Monroe, but we shared the same shrink, so I sat on the same couch,” he laughs. Even though the source becomes invisible once the tin is applied to the image, Berlant likes the fact that he knows where it came from.

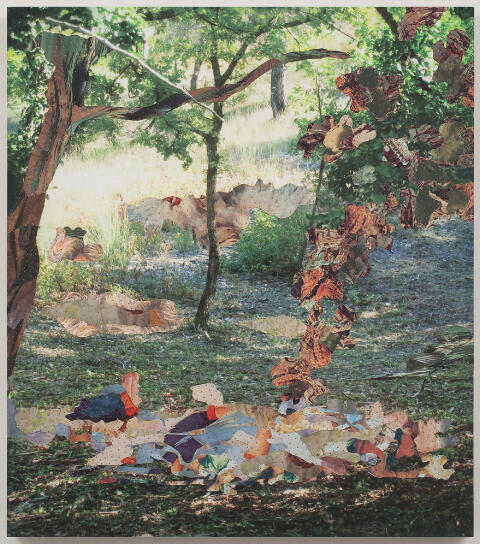

In this new series, Berlant has opted to leave part of the image exposed. He didn’t plan on it, but as the work progressed he liked what he saw. Putting the metal pieces on only part of the flat plane of the photograph, gives the work a dimensionality not seen in Tony’s earlier work. He likes the way it looks and feels. Conveying the essence of the place and the experience of going to Cezanne’s birthplace is critical. “The pieces are about going to a place where you can feel the presence of all these different things,” he says. “We were in Cezanne’s studio maybe an hour and a half before taking the photographs. I tried to take a highly subjective, indescribable experience and make it more graspable and concrete. I am trying to conjure up some sort of feeling or state that has to do with that place or that experience.” Although they may start as photographs of a particular landscape, the finished work bears little resemblance to a recognizable place. Berlant is not creating an artistic photo album, rather he is inviting viewers to take a step inward and check out the view from a new perspective – and that’s why he doesn’t refer to his work as landscapes, preferring instead to call them “mindscapes.”

Berlant’s involvement in the ambitious new art center being built in the South of France begins and ends with architect Frank Gehry, who is among a handful of dream team architects working together to design what will be, by all accounts, an extraordinary creative environment. Japan’s Tadao Ando developed the master plan, Gehry is charge of the music pavilion, France’s Jean Nouvel designed the wine cellar, and Italy’s Renzo Piano and Britain’s Norman Foster designed various other structures. Ando acknowledges the location is special because “Aix-en-Provence is the home of Paul Cezanne, the father of contemporary art.” When is came to designing the music building, Gehry wanted to incorporate contemporary art, and true to form, Gehry opted for something dramatic. That’s where Tony comes in. “I made these sculptures in the 1960’s, and felt they had a real relationship to Frank’s architecture. Back then I showed them at the Whitney, and then a few years ago we brought them out again for a show in Frank’s studio,” Tony explains. The sculptures are essentially buildings within buildings, made out of plywood and painted or covered in stainless steel. Gehry liked the three pieces, “The Forest, “The Last Temple, and “the Marriage of New York and Athens,” so much they almost became part of his studio permanently before he decided to incorporate them into his new design, which will incase the sculptures in three separate glass cubes integrated into the landscape to appear as if they are floating. Berlant is honored to be included and he is in good company – a large Frank Serra steel sculpture and Louis Bourgeois spider, among others will be integrated into an open air sculpture garden. The center is set to open next year.

Born on the East Coast but raised, for the most part, in Los Angeles, Tony calls New York City “the old country.” “I was part of a milieu of left leaning New York Jews in Los Angeles. I came out of that background,” he says with a chuckle. His father was a self-taught scientist and inventor, and when a young Tony started spending hours looking through a microscope and then meticulously drawing what he saw, Dad thought his son had a special interest in science, and the drawing was simply an off-shoot of that interest. In reality it was the other way around. For Tony, the microscope simply provided source material. The drawing was what mattered. If there was disappointment on the part of his parents, it didn’t show. His parents still viewed being an artist as a kind of ideal, so they were supportive. Even during high school, Tony made a point of seeing every exhibition that opened in Los Angeles. It was the late 1950’s – the beginning of a heady time for the L.A. art scene. The Ferris Gallery was making rock stars out of some young artists, Andy Warhol was making the rounds, and a young Tony was taking it all in before heading to UCLA. “I really wasn’t part of the sexy group,” he laughs. “I was on the fringe of that. I was part of the UCLA group, but even in high school I went to all of those shows. I got to know all of those guys and later we became friends. They were hip. The people who showed in the gallery I showed in were all ex-commies, all heavily into jazz. All into drinking and smoking dope, but they had a visionary artistic idea about what it meant to be an artist. People like Pete Voulkas, Emerson Wolford, Hazel Smith, and John Altoon. It was a different group not concerned with the New York power establishment at all.” This was the creative environment in which Tony Berlant came of age.

Berlant earned his membership card in the UCLA club first as an undergraduate where he studied under Richard Diebenkorn, and later as graduate student and eventual teacher. “I was not a teacher very long,” he says. “I didn’t know how to do anything else. If I hadn’t made myself offensive I would have gotten tenure at UCLA, and I would just be retiring now.” Offensive? Berlant declines to elaborate, but admits he did do things to provoke the administration – like taking his students to the State Mental Hospital for impromptu classes. “I had a very good friend who was there a lot (the State Mental Hospital),” he explains. “He was sort of a mascot to L.A. artists. He was actually in my high school class. Got thrown out of all his classes except the art teacher let him sleep in the supply closet, but he was very talented. When he would be incarcerated, I would bring him supplies every couple of weeks. So to me it was natural to take students up there. I put two students in each locked ward with painting supplies. It was not a scary or grotesque place, which I thought it might be. It was actually a very warm sweet thing. People who may not have been truly catatonic, but were still totally withdrawn and non responsive – they would start making things and even smile slightly. They would respond in some way.” For Tony that was an example of art making a difference, but the administration wasn’t amused. It wasn’t just the trips to the mental hospital. Tony admits that he had a total disregard of the collegiate value system. “As Diebenkorn once said to me. ‘ You think you disguise what you think, but they can see your contempt.” In the end, that rebellion cost Berlant tenure, and forced his career in a different direction.

Berlant is quick to point out that he genuinely liked teaching, and admired most of his colleagues even though, in his words, “they had come to believe their own publicity as professors.” He even shared an office with Bill Brice and Richard Diebenkorn. “I first met Dick as a student, and years later Dick’s studio in Ocean Park was directly behind my house. He would work six days a week. I could look up and see him painting. He was such a great artist. Horizon Magazine, which was a cultural fixture in the 1950’s, did an article on him, and I remember looking at the work with a magnifying glass – he was so good. He was also a very private person, so I was fortunate to be among his friends and I miss him,” Berlant says simply.

Acutely aware of history and a student of it, Berlant believes art can provide a blueprint of where we’ve been and perhaps where we’re going. “The more time that goes by the more interesting everything becomes,” he says. “A third rate cubist painting from Paris in 1918 is a pretty fantastic document because it captures the scent of Paris at that time. It captures the Picasso vibe. It’s an artifact.” All artists live and create in the context of their times, and to some degree their work is a reflection of that. Berlant embraces that idea more than most. Book shelves along one entire wall of a room adjacent to his studio showcase his collection of Pueblo rattles – dozens of folk art pieces made by Hopi Indians. In specially designed drawers built underneath his studio worktables, Berlant keeps his collection of prehistoric rocks. The drawers are divided into sections so that each rock has it’s own compartment. “They are more than a million years old,” Tony says with reverence. “I have always been a rock collector. I play with them all the time. I like holding hands with history.” Berlant’s own work reflects this respect for all that has come before. Back in 1982, a writer for the Village Voice used the term “urban archeology” to describe Berlant’s work, and it’s a description that holds up almost thirty years later. Infusing his work with an intangible emotional pull, Berlant immortalizes the landscapes of our times in a unique and contemporary way. “I hate the word spiritual,” he says. “All adjectives are totally inadequate. All I can say is that I see God in nature.”

Berlant is a down to earth intellectual. There is nothing snotty about his approach to art or life, and he is clearly uncomfortable with elitism. “If someone says they are an artist that sounds like phony baloney – sounds like a poser to me. So even calling myself an artist is hard,” he explains. “I revere it and I’m uneasy with it at the same time. The whole art scene is overwhelmed with desperation. Dedication, good intentions, smarts, skill – they are necessary to get out on the track but it does not ensure that anything special is going to happen. The morality of your attitude does not guarantee good art. It’s too bad.” Feeling lucky to be among the relative few who are noticed and acknowledged for their art, Tony calls it a small miracle. “If you are a filmmaker you have to get funding, and then people change your vision, but for someone like me when a show happens the only excuse I have is that this is the best I can do. Which is actually wonderful. It gives me absolute freedom,” he says with a grin. Berlant clearly likes the freedom success now affords him, but he also knows he’s only as good as his last exhibition. So as he gears up for the final push before his upcoming show this summer, Berlant admits to feeling the pressure, but he also has faith in the process. “I know there is something special about my new work because with each piece I feel like I don’t know what I’m doing and it’s an impossibility, and then I really like what happens. It’s not a big miracle but it is a miracle.”