Ring the alarm

Written by: Ben Basmey

“It feels like I am in a movie about my life but I don’t have the lead…” a fascinating statement of clarity from TR Colletta – one that allows him to see abundant abstractions in every rigid reflection. He understands that the journey to his core is a compass-confusing maze. So rather than barreling through barriers and speeding down streets to nowhere, Colletta has chosen to enjoy the twists and turns of time. “The artistic process for me is a lot like jumping across a lake on lily pads,” Colletta quips. “You hope there’s one in front of you to jump to before the one you’re standing on sinks.” His hopscotch through life goes something like this: Grammy-award-winning singer and former church organist/bagpipe player turned full-time painter with an unquenchable thirst for history (especially British) who grew up Catholic in Buffalo but ended up breathing better in the free, yet graffiti-stained air of San Francisco. All that absorption has added substance, but it has not made him fat. Colletta’s brain is clever, his brush loaded with insight and his strokes riddled with secrets worth knowing. Understanding what lies beneath means digging deep without fear of the chords that will be struck along the way.

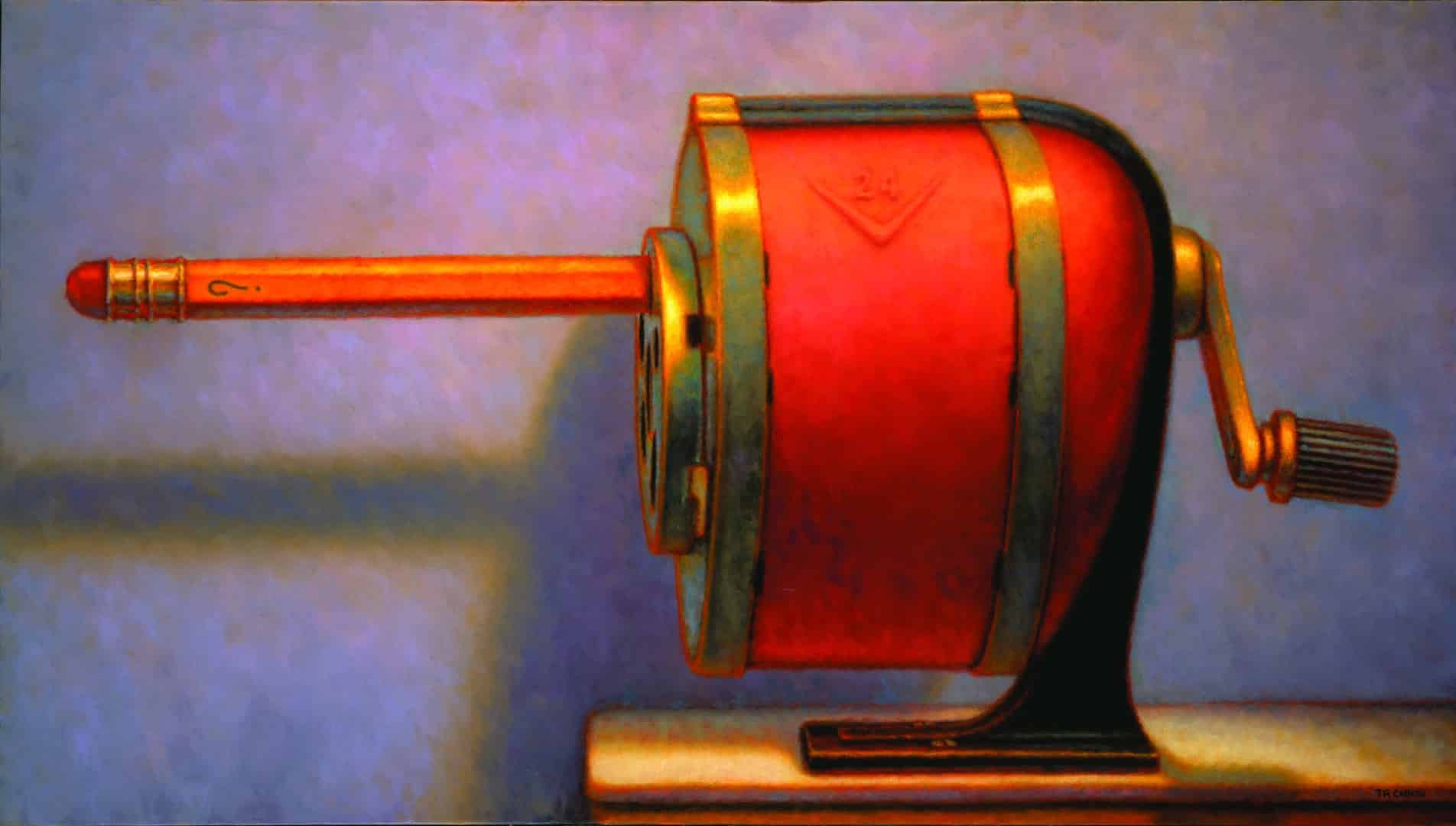

Colletta calls his paintings “contemporary exercises in recognizable memories.” The objects themselves are the initial draw. They have a familiar color, shape and style, and although they make room for differing experiences, most have universal functions. For instance, we push a pencil or bang on a typewriter to help us string words together. But communication need not end with the script created. And that’s the brilliance of a Colletta canvas. After first identifying with the representational, the subtle surrealism begins to seep to the surface. In a piece called “Strike One,” Colletta investigates the cost of “free” speech. He painted three parallel, yellow “American” pencils. The middle one has a worn eraser and is broken in two places. It’s the equivalence of a bitten tongue wondering how many chances it gets to say the “wrong” thing.

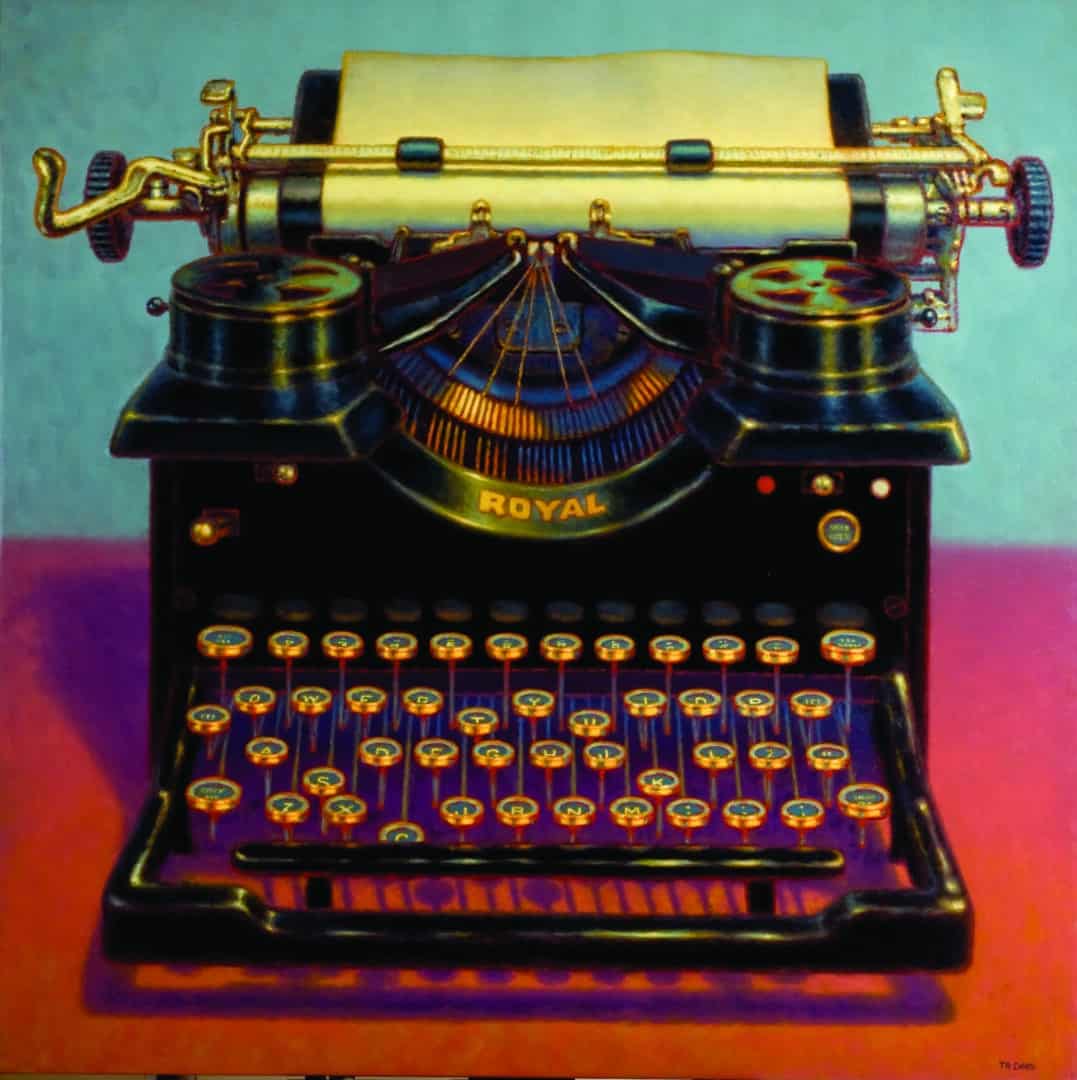

Regardless, we know words don’t come easy; oftentimes they don’t come at all. Prose is what writers do. But what happens when the brain farts and the only letters that make sense are the “P” and the “U?” Colletta vowed to create a visual to explain the virus known as “Writer’s Block.” However his head-scratching piece features only a pristinely oiled typewriter. It seems as though this black beauty should serenade an old author with sweet sentences. But even this magnificent machine has felt the touch of frozen fingers. Look at its keys! They all have question marks on them! The sheet of paper rolled in it has been hit with just one small stroke: ?

Dick Wolf created “Law & Order.” Solving crimes is what he does. But even Wolf can’t beat the system when mental handcuffs lock him down. So he bought Colletta’s canvas and hangs “Writer’s Block” on his wall praying for its execution.

Colletta is the Agatha Christie of art: clues, clues and more clues. It’s a visual journey that doesn’t necessarily end with a solved murder. But it does make statements and pose interesting questions about what may be killing our society. Take guns for example. At first glance, Trigger Happy appears to glorify them. Hell, our fascination with weapons dates back to childhood – watching old Westerns and playing cowboys and Indians. Colletta dusts off that nostalgia with two silver-plated pistols tucked neatly in a 1950’s-era Roy Rogers leather holster. The rusty buckles give the piece even more true grit. But just below the brass adorning the belt is a message about control. The odd-looking orange bullets have white tips and yellow caps. That’s right, the ammo is actually candy corn – sweetness before shooting.

What’s the root of all evil? A glimpse at National Cash Register seems to have the answer. The gloomy total of $66.60 makes it easy to understand who’s opening and closing the till. In Texan Economist, a one-armed bandit slot machine comes complete with a blazing Smith & Wesson. The goofy, ten-cent machine has hit a jackpot but with backwards dollar signs. “I almost put George Bush’s face on it,” Colletta admits. “I was so angry when he bankrupted the treasury the first year he was in office. I didn’t do it, though, because I thought it would be pushing it.” So true to Colletta’s M.O., he hinted at it instead. As for right and left-winged pundits, Colletta has a soft jab for them, too. He painted an old radio broadcast microphone with the motto “Voice of America” labeled all over it. The steam rising from the metal gives the piece its title, Hot Airwaves, suggesting we consider not only the message being promoted, but also who’s saying it and why. One of his latest works is a landscape of Golden Gate Park. From a distance it seems like the ideal place for birds to chirp. But viewed from up close, it’s clear that the atmosphere is covered in jigsaw puzzle lines. Three pieces appear to be missing. Maybe they’ve been swallowed up by carbon emissions or buried under a heap of hazardous waste. Subtle commentary in a not so subtle world. “We’re taking chips out of nature all the time,” Colletta states. “Rather than overt political statements, I like the work to be a bit more benign, so it can live in people’s homes and not be so in your face, in your face, in your face.”

In 1996, Colletta bought a condo a block off of Market down from Union Square. It screams San Francisco: the hustle and bustle of a working city surrounded by the ragged faces of homelessness. Romantic restaurants are short walks away, while a stone’s throw in either direction will crash through the window of a newly opened pot clinic. Colletta’s pad is a cozy two-bedroom with lofted ceilings and just enough space to paint. Every day, all day that’s what he does. Mix in a dry martini or a scotch at night plus a nice workout at the gym and that’s how most days are crossed off on his calendar. However, the path that led towards this comfortable routine has been anything but.

Thomas Colletta grew up in Tonawanda, New York. It’s upstate and a bit uptight. Church was mandatory, and buttoned-up behavior was expected for Tom and his five siblings. Mom had a piano, and a young Tom found his voice through music. He picked up the French horn during his junior year in band and soon leapfrogged to first chair. In college Tom engineered his course load to include music and history classes, eventually graduating with a B.S. in Graphic Design. Summing up the latter interest is simple: Tom traveled with a photograph of the queen’s coronation in his first car, and at the age of 19, he traveled through Europe in a three-piece suit. Around that same time, Colletta began composing his own music. He later sang professionally with the Connecticut Choral Artists (CONCORA), and even picked up the bagpipes. “My first parade was St. Patrick’s Day,” he reflects, “and I marched over a manhole with my kilt. I felt like Marilyn Monroe in ‘The Seven Year Itch.’ It was like a whole new world.” Music not only colored his wardrobe plaid, it also paid the bills for a long time on the East Coast. Colletta spent 14 years as a church organist. He loved the sounds blaring from the pipes each Sunday. But 52 weekends a year as on-call memorial service musician had taken its toll. It wasn’t just Chopin’s “Funeral March” that was bringing him down; self-discovery had left him singing an unfamiliar tune. So, at the age of 40, everything he knew was about to change.

“Gay did not exist in my Catholic family in New York in the sixties,” Colletta states matter-of-factly. “Even in my own psyche it did not exist.” But after twelve years into a marriage with a wonderful woman, Tom’s mind caught up to his chemistry. “Living in a closet is a waste of time,” he says with some lingering pain in his eyes. “I never did live in a closet knowingly, though. It was a tumultuous experience going through a divorce and figuring out what it meant to be a gay man.” After a rough year alone in New York City, Tom packed the three-foot long, to scale model of the Titanic he’d built along with its glass cabinet, shoved them in the car and drove cross-country to California. Crossing into the Golden Gate meant freedom, but fully embracing it was a challenge like no other.

In the eighth grade, Tom’s parents bought him a set of oils, and that year he painted a bunch of fruit and won “Honorable Mention” at the community art fair. Thanks to that ribbon, he’s had a brush in his hand ever since. No formal art school training, though, just some private lessons and countless hours of trial and error. He began signing his canvases TR Colletta a long time ago, thinking the initials stood out better than some guy named Tom. But what really sets his work apart is not an autograph – it’s the meticulous attention to detail, the way light and shadow dance with each other and the expression willed into his subject matter. Colletta worked at a photography studio for a few years in Niagara Falls after he got out of college. Tricks from that trade taught him how to diffuse backgrounds and pop out a third dimension on his canvases. When he lived back east, Colletta painted as often as he could, mostly urban and architectural landscapes, plus some portraits, too. “I took my first piece to a gallery in 1979, and it sold. It was a painting of the old statehouse in Hartford, Connecticut,” he laughs. “From then on, anytime I needed money I did a painting of the old statehouse in Hartford, Connecticut, like Monet and his Rouen Cathedral.” Despite selling well, it would be another 16 years before TR Colletta would call himself an artist. He felt he had to earn the title first.

In San Francisco, Colletta committed fully to his craft. He took temp work as an errand boy to help pay the bills, but every other second of his waking hours were spent painting. At the time, his signature style was striking architectural landscapes of old, East Coast Victorians. While they were technically sound, San Francisco galleries didn’t want them around. So TR found himself in an artistic limbo – a painter with things to say but no audience willing to listen. “You want to have a voice and you want to express yourself, but it’s not art until it connects,” he explains. “In other words, all art is self-expression, but not all forms of self-expression are art.” Then in 1995, three years after he landed in the Bay Area, TR finally stumbled upon his professional intersection. It was a red Department of Electricity fire alarm on a downtown street corner with “break glass” and “pull hook down once” instructions written on it. The object seemed to be symbolic of so much: a call to action, a reassurance of direction and even a saving grace. “I had been looking for an image to make my work a little more contemporary,” Colletta reflects. “I felt the fire alarm incorporated various elements of my life: obviously painting, but with all the fires the city had experienced, there was also an historical component to the object, and most importantly, I felt it represented possibilities.” Included in that realm, the courage to call himself an “artist” for the first time.

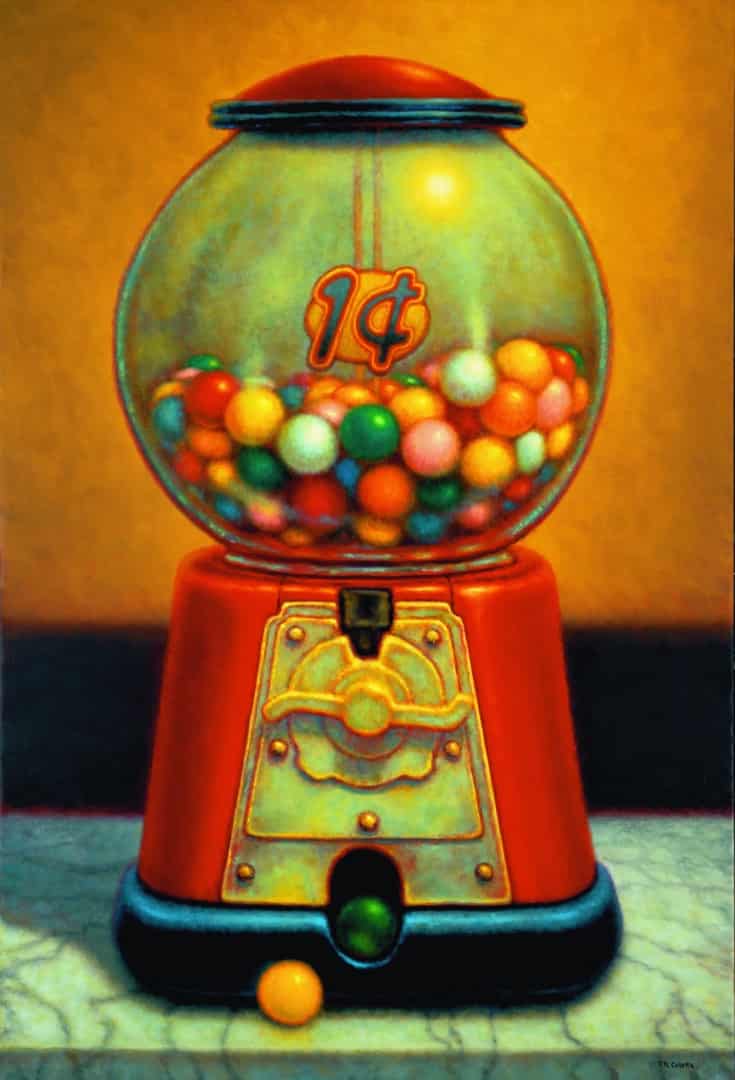

Colletta’s investigation of objects bounced around from industrial to recreational and even experimental: electric meters, mailboxes, telephones, pinball machines, diner jukeboxes, movie popcorn makers and flying gumballs. With newfound room to explore, there was no capping his creativity. “I found that by turning a baseball a certain way the stitching creates a yin/yang,” he says. “I lit the piece from top to bottom and then put an emblem on the top to get a dark spot in the white area, and I put a reflection on the bottom in the black area.” Turns out Cy Young Award winning pitcher Barry Zito is into Eastern thought and liked the piece so much that he bought it on the spot.

It was a lucky strike, but other experiences in his career have been as surreal as his work. In May of 2001, Colletta revisited the subject of fire. He created a triptych out of three firemen’s hard hats – one yellow, one black, one red, each 32 inches wide. Then in August, Colletta created another fire alarm, this time a wall mounted device with an ominous hand reaching out from inside the breakable glass. He called it The Calm Before… Then, in September 2001, Colletta began work on a New York-style ticker tape machine. That piece was resting on his easel the day the World Trade Center towers tumbled.

In 2002, “Ghost” actress Whoopi Goldberg bought the fire hat triptych during Colletta’s first New York show. It was just another in a string of “spiritual coincidences” in his life. Years before he bumped into a random woman in San Francisco who seemed to know an awful lot about who he was and what he did. Seems she forgot to mention that she was a psychic until the end of the discussion. She left Colletta with one parting suggestion – a gallery that she thought would suit him perfectly. TR rollerbladed down there a couple days later but didn’t see how his art would fit. That was that until two years later when he saw a beautiful blonde man walking out of the Castro Theatre. “I tried to think of something to say but nothing came out,” TR says. “I kicked myself for being so shy.” But low and behold, three months later he saw the man again at the same theater. “You don’t often get a second chance in life,” he continues. “This time I went in and I handed him my card. I didn’t mean to be presumptuous, but in the Castro you can be pretty sure.” His name was Kord, and to TR’s surprise, he called. It was on the second date when Kord began talking about his job as a gallery administrator, and incredibly, it was at the exact same place the psychic had once recommended. Needless to say, the couple has been together ever since, some 14 years, or as TR says, “In the gay world that’s a golden anniversary.”

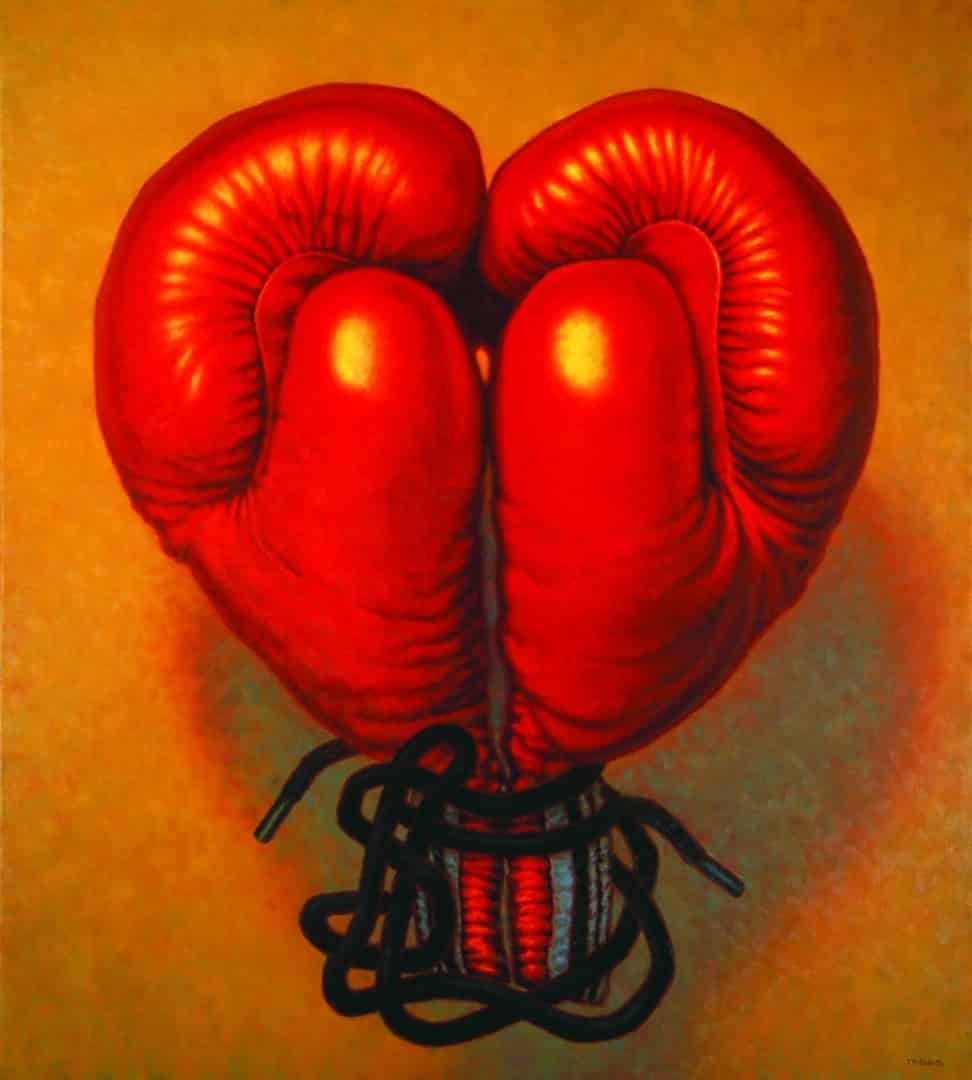

A gleaming Victrola record player is frozen in time on the easel in Colletta’s studio. For just a dime it spins a rhyme that sounds a lot like the story of his life. It’s a self-portrait of sorts. “My attempt at Chuck Close,” he snorts – where music and art collide on a canvas full of pride. The clue that’s final can be found on the vinyl as streaks of color glow to Harold Arlen’s “Over the Rainbow.” You see, why should things be cut and dry when they sound so much better witty and wry? Take boxing gloves, as yet another example. They’re used to dismantle someone, right? Sure, but even Cassius Clay has a heart – one that can best be seen when the red leather comes together thumb to thumb. But the tie that binds in this case is the lace. It twists and turns into a dollar sign creating the fine line between love and money. Colletta’s painting professes that there’s even more in store to a pay off punch when you figure out what you’re fighting for.