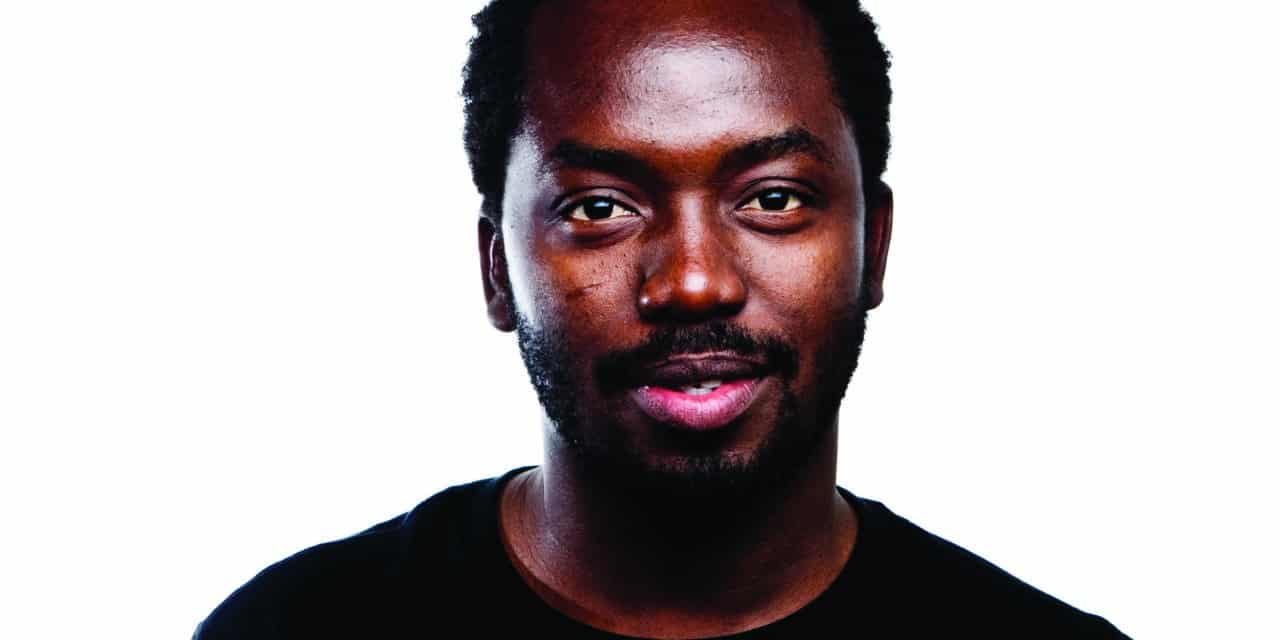

KAReem Ralph Amin

Written by: chantal gordan

Photography by: zack gemmell

When I arrive at painter Kareem Ralph Amin’s studio in San Diego, the first visual key to his life that he shows me isn’t a painting – and it isn’t a drawing. Rather it’s an old inkjet-printed photo pasted onto a piece of tagboard. In the shot, an 18-year-old Amin is sitting at a desk, headphones on, beaming a puckish stare into the camera. Beside him, his best friend Dwayne Adams – earnest, at attention and clutching his leather bookbag –plays the sidekick and foil. Both are waiting for their technical drawing class to begin.

“He was always the quiet one and I was the rudeboy,” Amin chuffs, using the reggae slang to mean a Mr. Popularity type. “I was in the forefront getting all the attention.”

The shot was taken in Georgetown, Guyana, where Amin, now 32, was born and raised by his father and stepmother. At age 20 he moved to another Caribbean nation, Antigua, to live with his mother and her family. “Antigua was sweet; Guyana was raw,” he says. “I enjoyed both sides. Living in [Antigua] you felt like there was a lot more to gain with regard to financial status; tourism is a big source of the wealth for that country. But at the same time Guyana for me was the grassroots, the foundation. Living in Guyana was a way for me to acquire a good sense of business and being independent.”

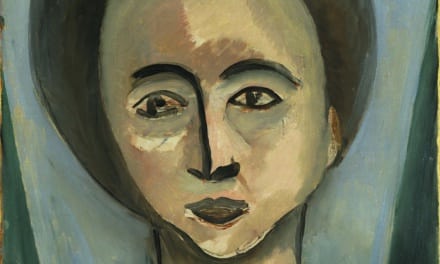

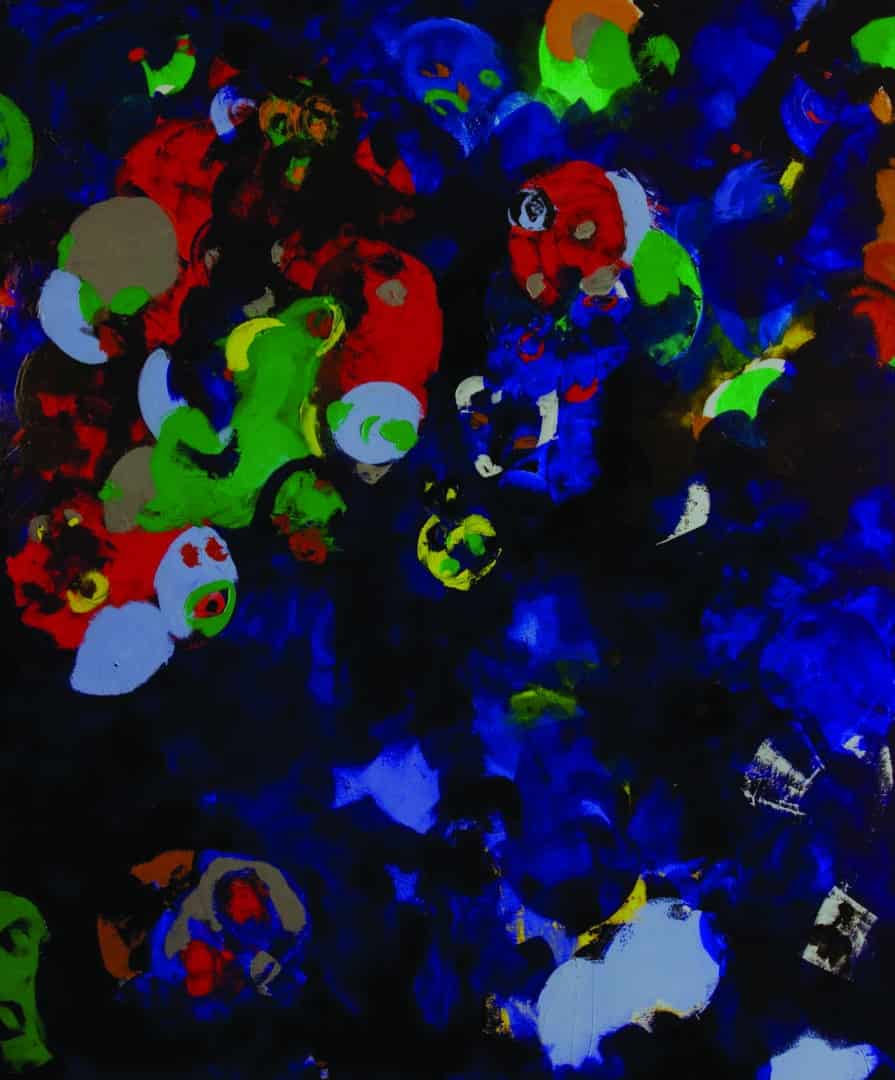

Introvert/extrovert, sweet/raw, rich/modest; the same tension between opposites that has shaped Amin’s life is also evident in his work. He energizes contrasting (and at the same time harmonious) colors into dancing, overlapping brushstrokes, a feature that has become his signature. Human figures and faces emerge between, beneath and on top of these layers. His work is abstract portraiture in motion. To wit, in his recent piece Unusual Faces, a scarlet dash upon a blue swirl becomes Amin’s comical, visual shorthand for a smile. “I think he helped mold us right,” 32-year-old Amin says of his dad, a journalist. “He provided what I called the one-way street program – get up every morning, listen to BBC news, go to school, come back home. I did track and field, and soccer – things that really would spice me up – but soccer was my main thing. It was a smart sport to me, like a chess game when you’re on the field.”

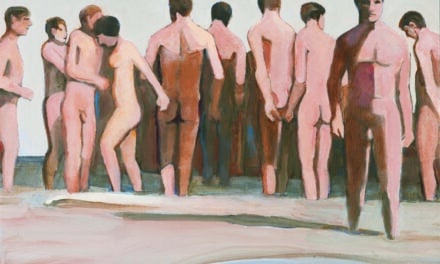

Some of Amin’s pieces radiate an isolated, last-man-on-Earth feeling; his early breakthrough Harmony depicts two figures carrying walking sticks, one person taller than the other, and they are proceeding perhaps into a light, perhaps toward a chosen path. Other paintings, meanwhile – like his new, dizzying diptych Enlightenment – are gridlocked, busy, voyeuristic. It was Amin’s first afterschool job he had when he was 13 that taught him how to spot moods and personalities on an abstract, essential level. This was the deal. His dad would buy Amin and his brother 100 copies each of the Guyana Chronicle, and they would sell them at night and on the weekends if they wanted extra spending money. “On Wednesday nights the supper clubs would finish at four in the morning,” says Amin. “Basically we would wait until the club was over and everyone would come out and buy newspapers. [My dad] was there to shield us, but I think it opened up street sense to me, helped me learn to identify people.”

At 22 he left Antigua and moved to San Diego. “Straight to San Diego – I didn’t go to no Brooklyn, no Miami – no place where [a lot of] Caribbean people are,” he says, laughing. “At first it was a culture shock.” Although his background was in telecommunications, when he arrived in California he began working in the sales departments for Frazee and Vista paint companies, and at home he began painting during his free time. One day during a lunch break he walked into a furniture store in well-heeled Encinitas, where he saw paintings on offer. “I asked them, ‘Do you buy artwork and sell them, or do artists just bring in their artwork and put it on show?’” he recalls. “Then they asked me, ‘What do you do?’” And without missing a beat Amin replied, “I’m an artist.”

Long story short – he displayed three of his works at the shop, and all three of them sold. In two weeks. Talk about an “aha” moment. “The first paintings were very primitive pieces – rich earth tones, no primary colors, none of that. Just umber, brown, dirt color. It was just…raw,” says Amin, who counts Marc Chagall as an influence.

It was around this time his grandmother, another formative force in his life, passed away. “Painting at home was a solace moment for me.”The morning after he returned from her funeral in the Caribbean, and with his mind made up to start his own decorative arts company, he walked into Vista Paint and quit. Before long, his library of wall finishes (think fresco, Tuscan, drift patterns) was in high demand, and in 2003 he used that money to open his own fine arts gallery in the hot design burg of Solana Beach, in northern San Diego county. His following continued to build. Buyers included an interior designer, motivational speaker Steve Farber and residents of Tony Fairbanks Ranch. Two invitations to Florence’s biennale followed.

The exuberance and high energy levels of his most recent art and of the artist himself seem to feed off of each other in one continuous loop inside Amin’s new studio in Golden Hill, a neighborhood in mid-gentrification just east of downtown San Diego. (Amin has since closed the Solana Beach gallery.) Here cafés with ambitious tea menus and patios groaning under hipster weight coexist with taco shops and flower stands. Amin recently found an apartment here, too. So what’s next on his agenda? In September he’s in Tuscany for Biennale di Chianciano, and October 2 – November 6 is his solo exhibition at Jett Gallery, a hip newcomer on San Diego’s art scene. Next year you can find him at Art Show Zurich. When he does slip away from work, he gets his West Indian foodie fix at Eva’s Caribbean Kitchen in Laguna Beach, owned by a fellow Guyanese whose conch fritters draw tourists from all over California.

These days Amin says he’s finding a strong aesthetic kinship in architects, Zaha Hadid and David Adjaye to be exact; the latter was recently tapped to design the National Museum of African American History and Culture in DC. “Their work is very simple but you understand the creativity that’s there,” says Amin. “That’s what people are looking for – that surprising, dangerous thing.”