LARGER THAN LIFE

Written by: ERIN CLARK

Photographer: BILL APTON

Sculptor Karen Shapiro follows the same routine every morning. She wakes up, turns on the espresso machine, lights her first Marlboro Light of the day, says hello to her four cats, pours a cup of coffee and then heads to her studio where she will spend the next eight to ten hours. She lives in Gualala – a tiny town on California’s Redwood Coast about four hours north of San Francisco. It’s a funky, artsy place that is home to a world-class cultural arts center and a vibrant art community. You can’t get there quickly, no matter what your mode of transportation. California’s famous Pacific Coast Highway winds its way north offering spectacular views, but it’s slow going. When you finally arrive in Gualala the sun is usually shining – a quirk of geography often shelters the hamlet from the fog even when the rest of the coast is socked in. “I always wanted to live in the forest by the ocean, and now I do,” Karen explains. “I’m about two minutes from the ocean, just off Highway One. I can hear the seals barking, and just driving into town I’m looking at the ocean. It’s gorgeous.” But truth be told, Karen doesn’t see the ocean much, doesn’t go into town all that often, and doesn’t get out in the sunshine. Most of her time is spent in a converted garage with slabs of clay, three kilns and temperatures that can singe eyebrows. If it sounds monotonous don’t mention that to Karen. She’ll be the first to tell you she is as happy as a pig in clay.

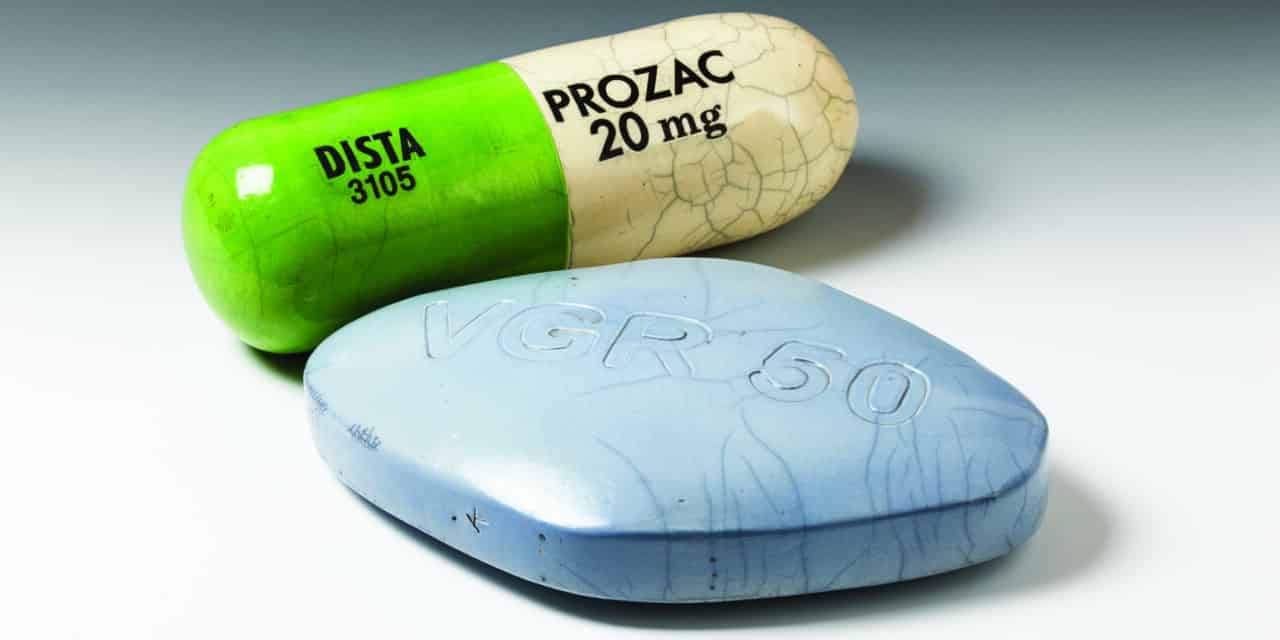

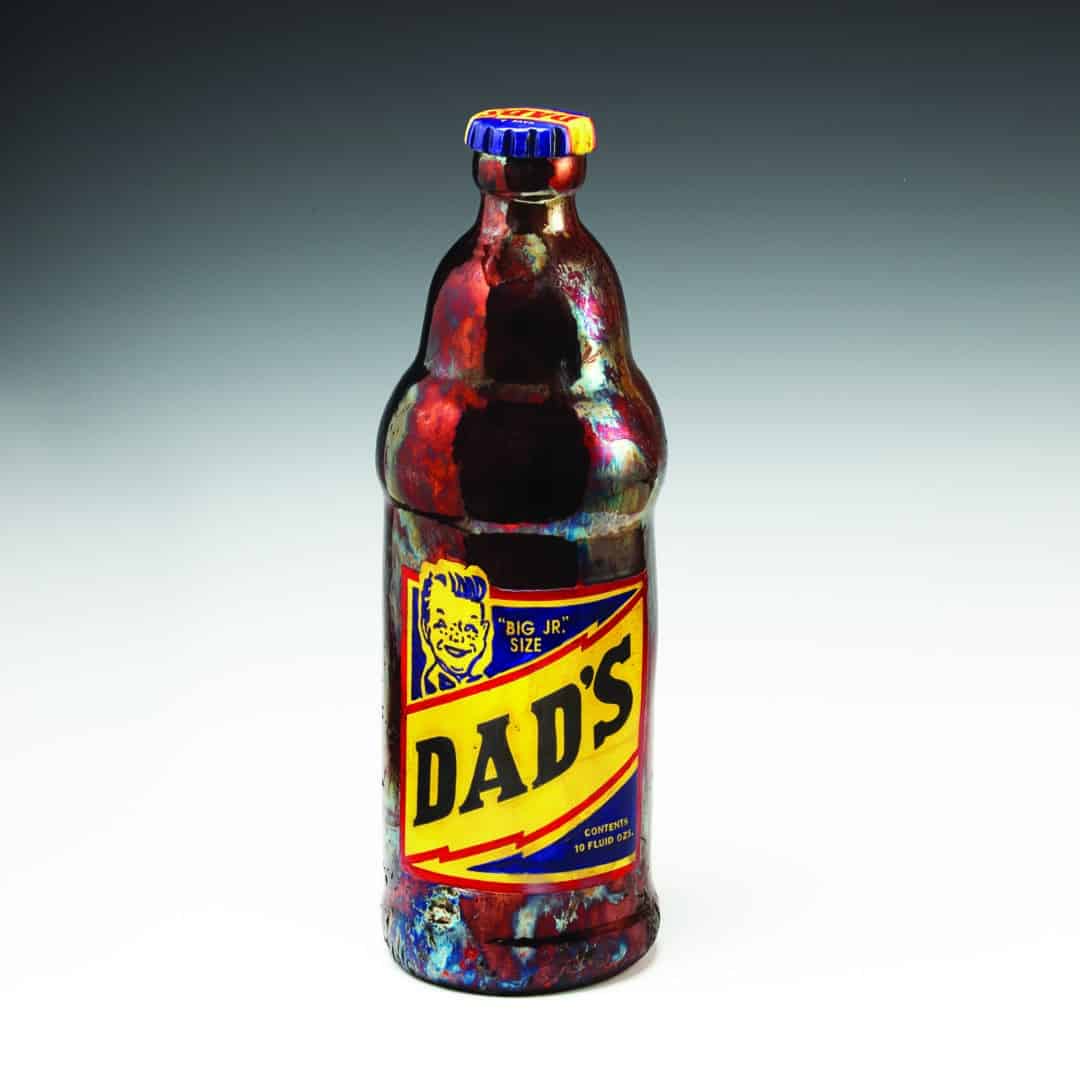

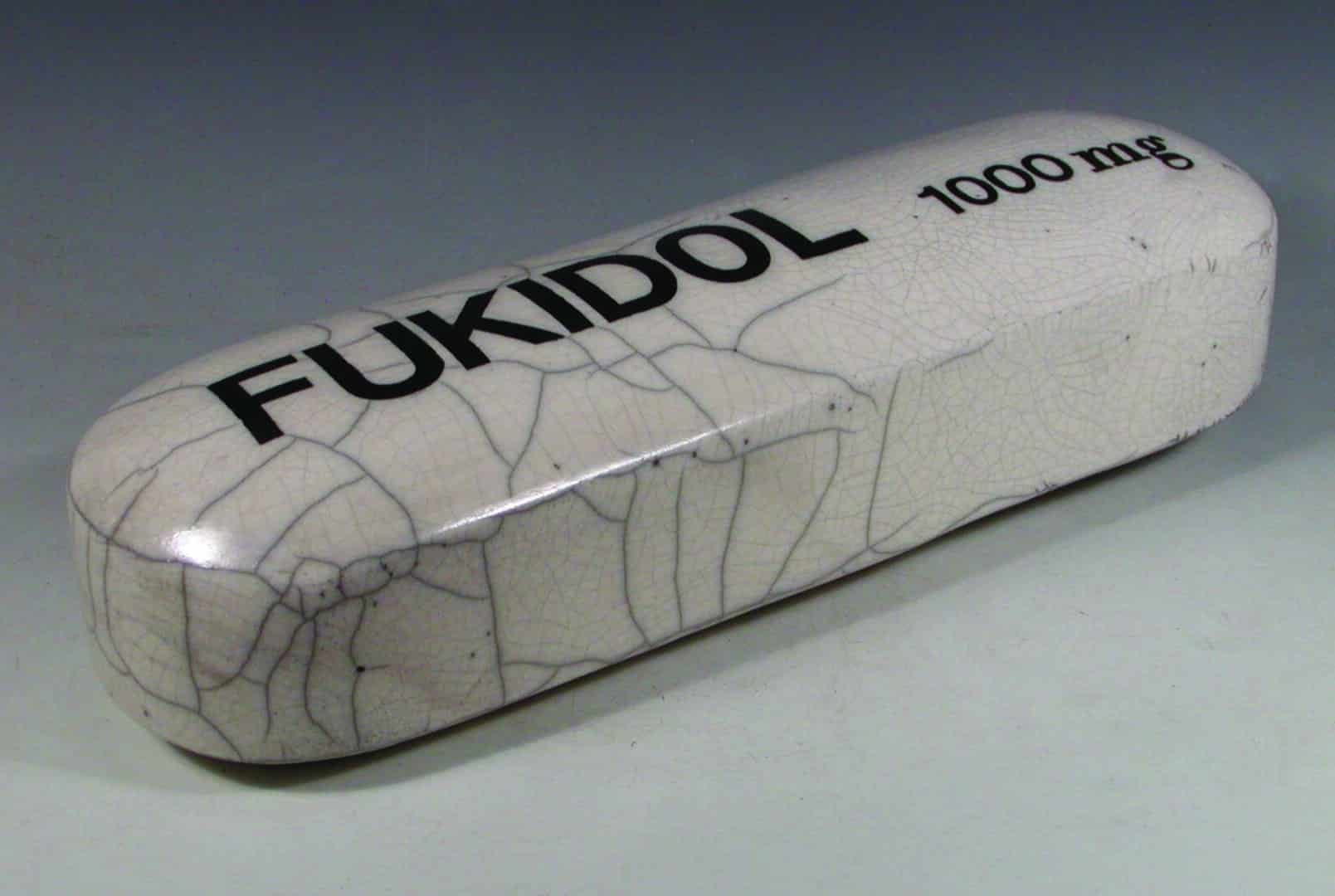

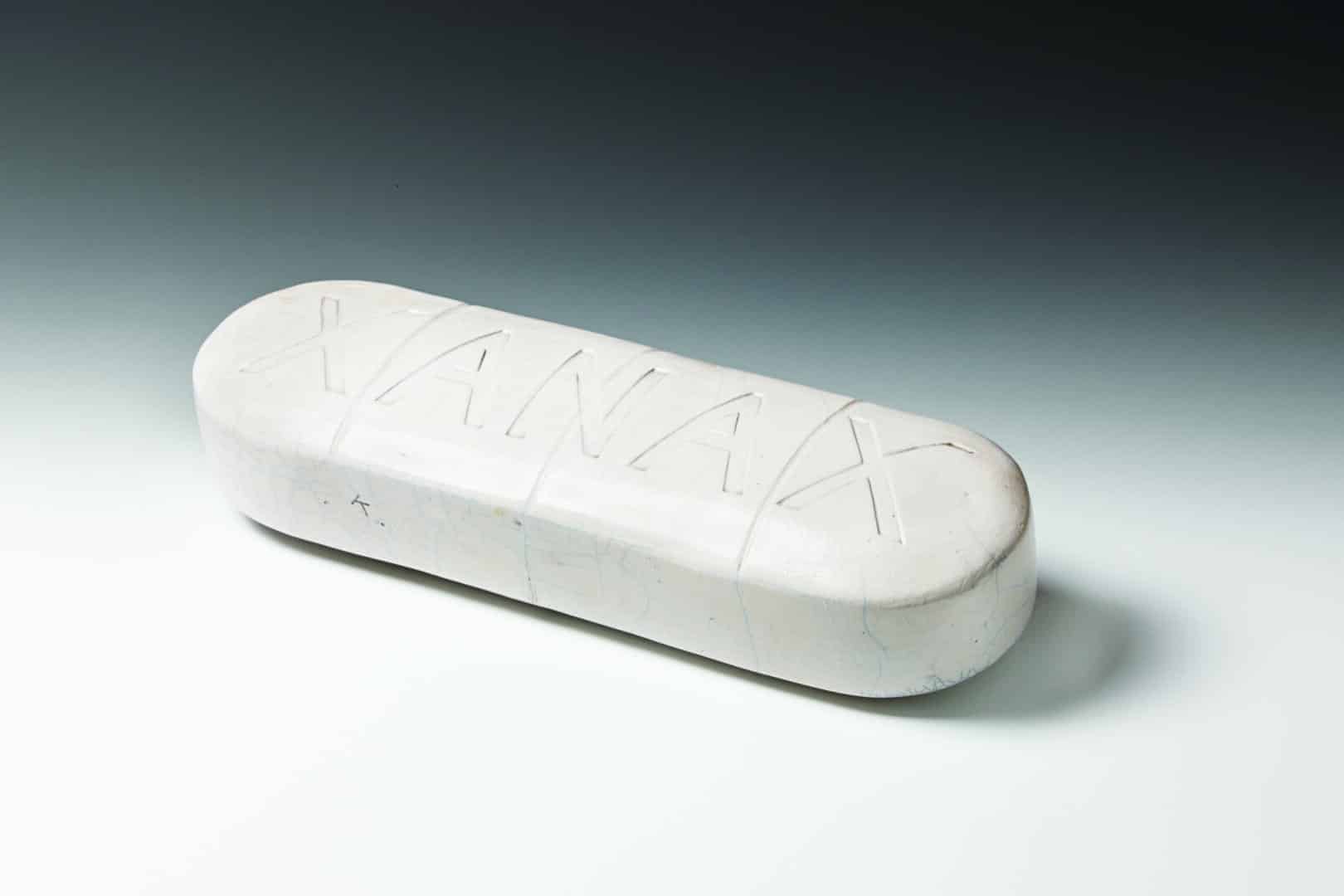

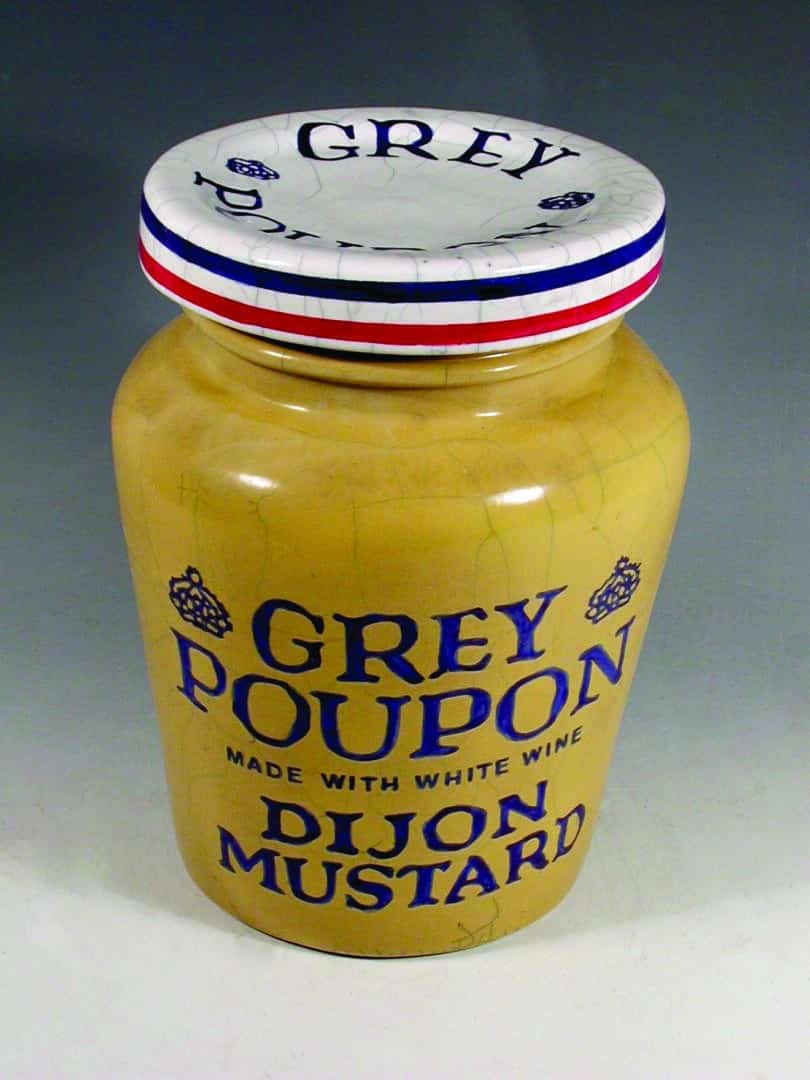

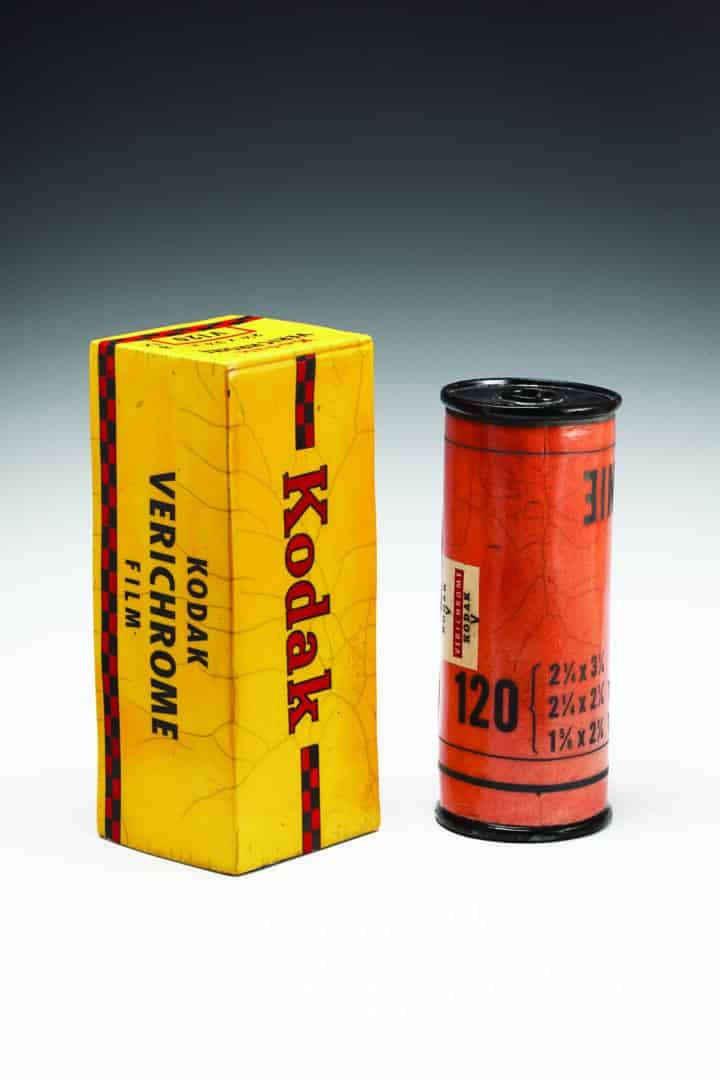

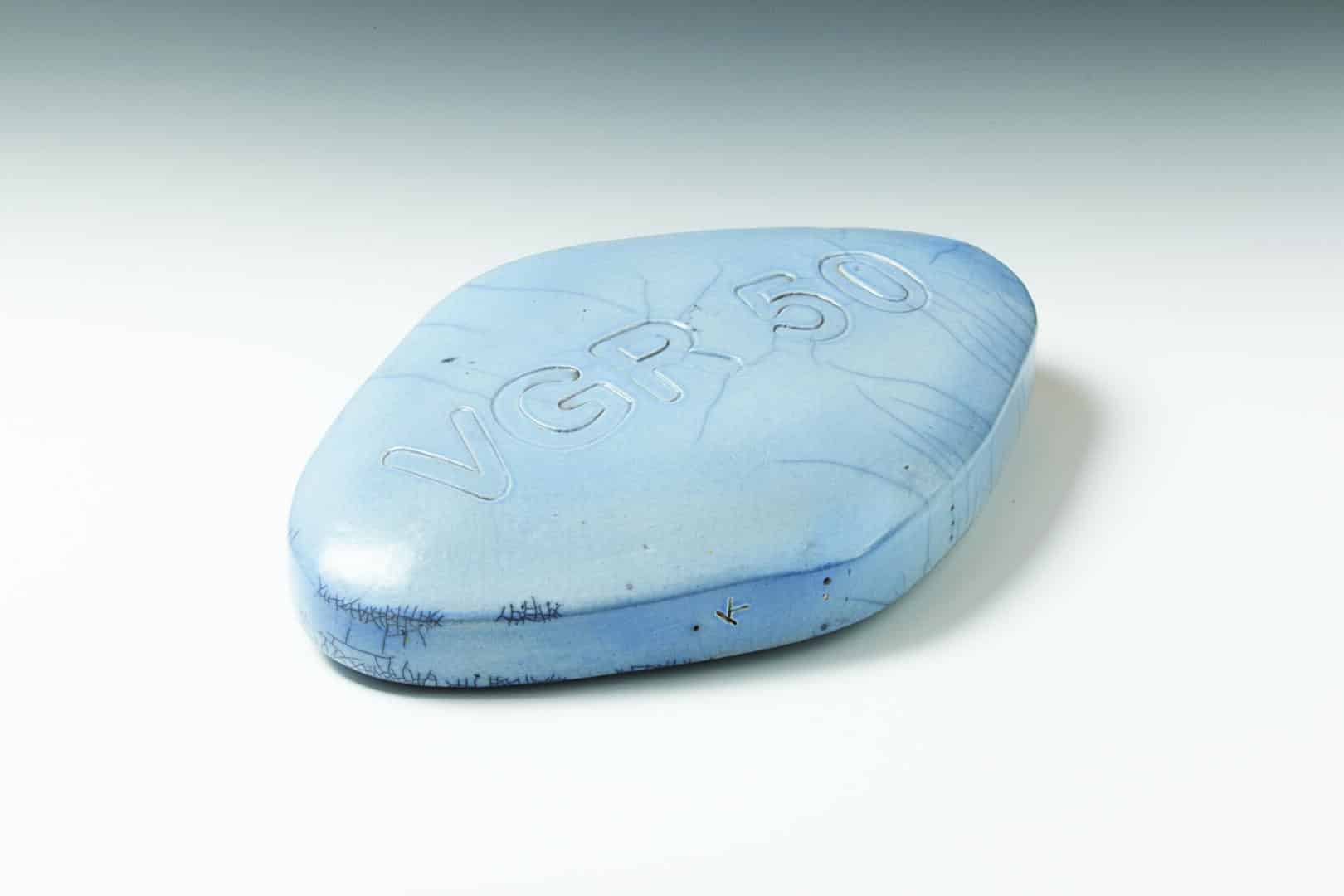

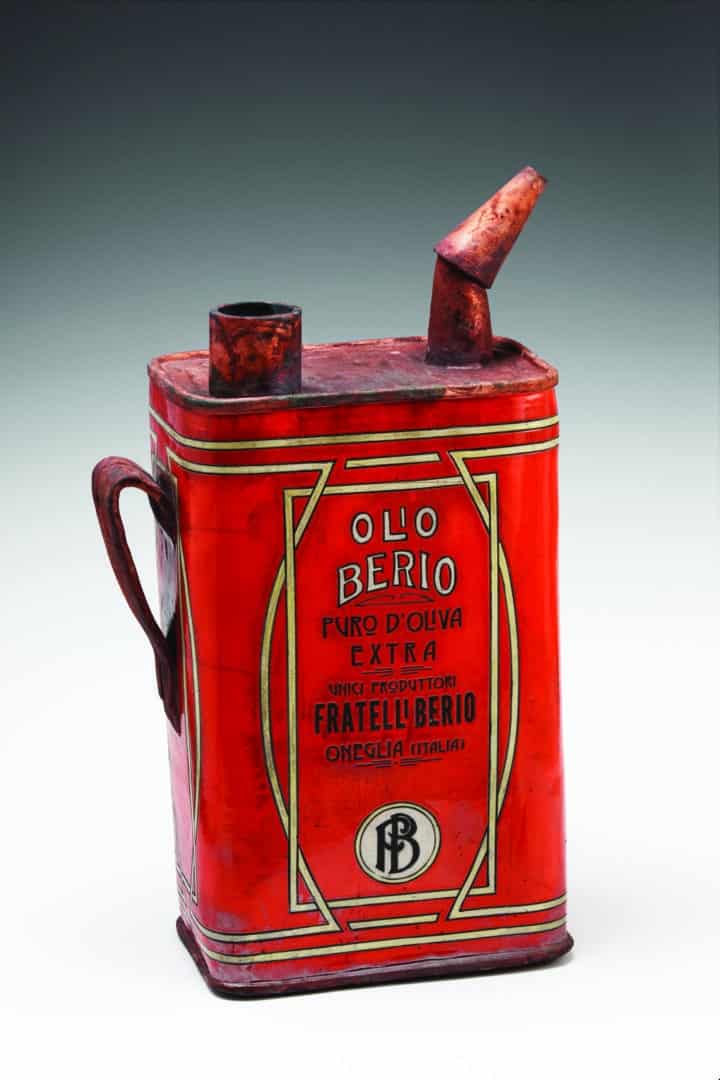

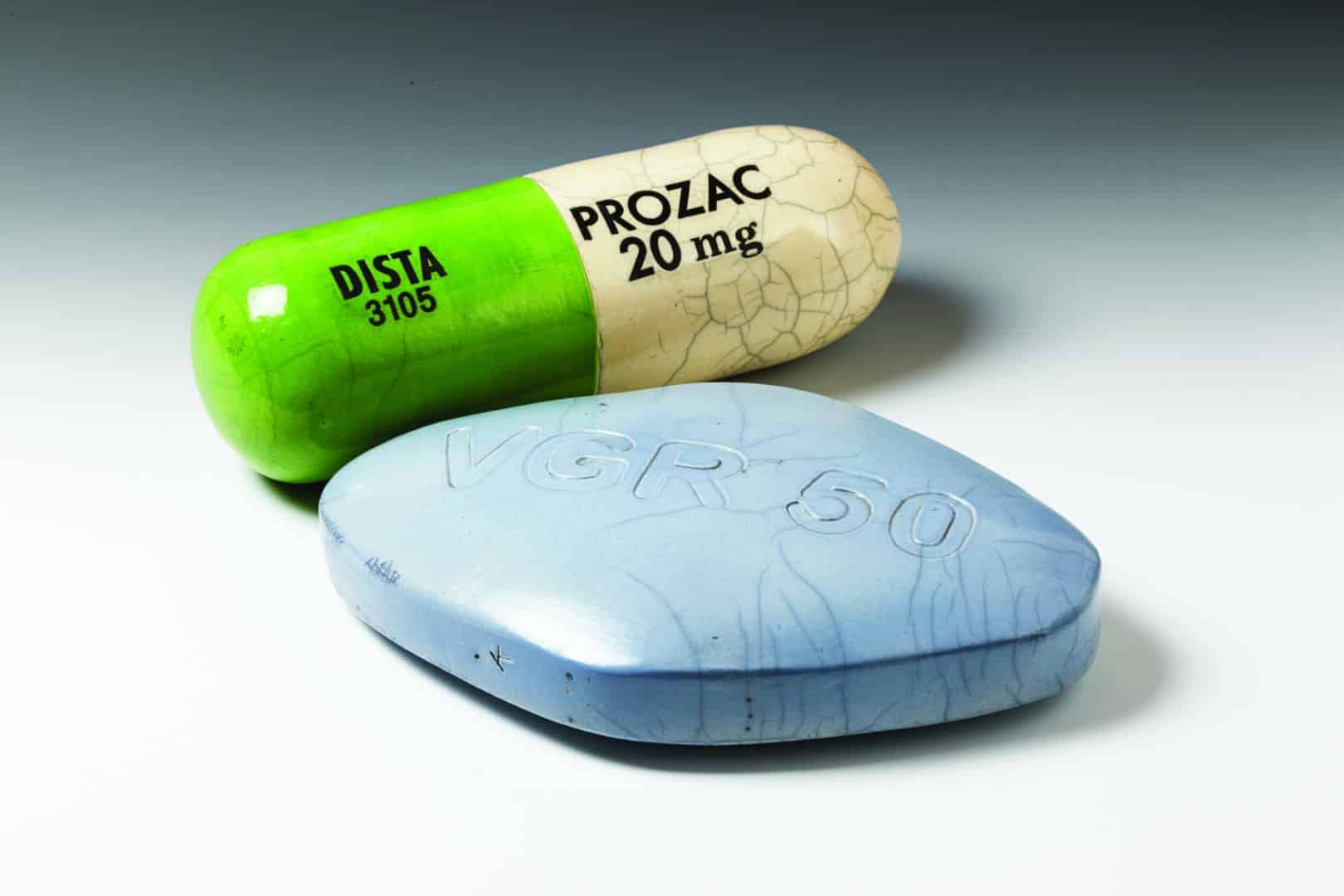

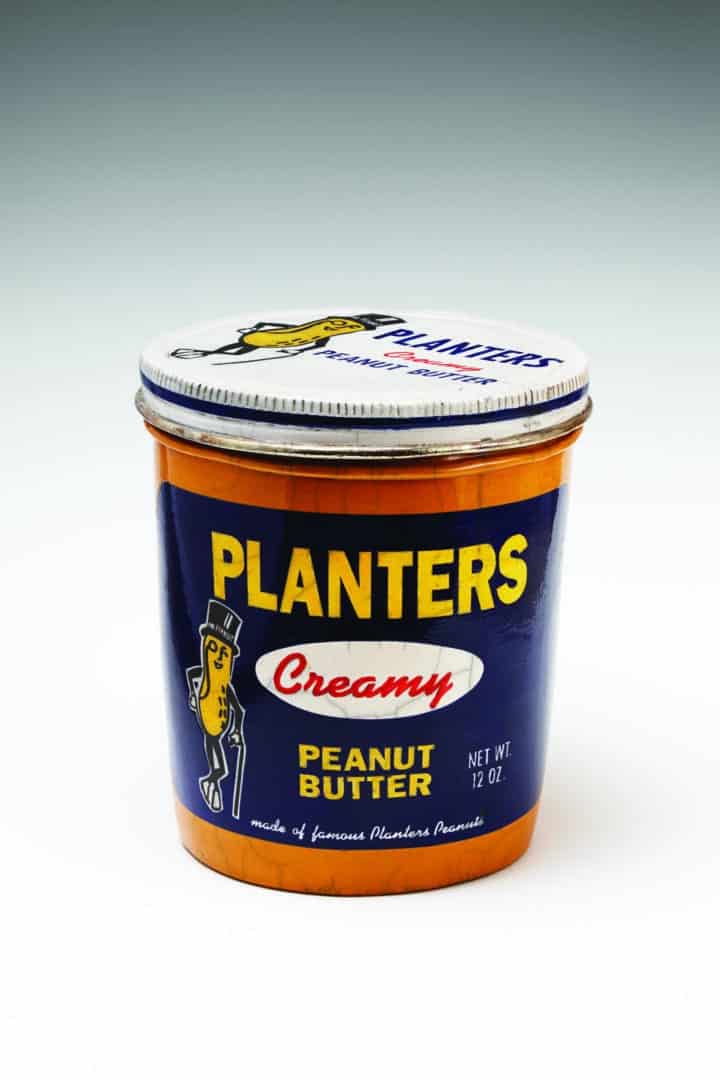

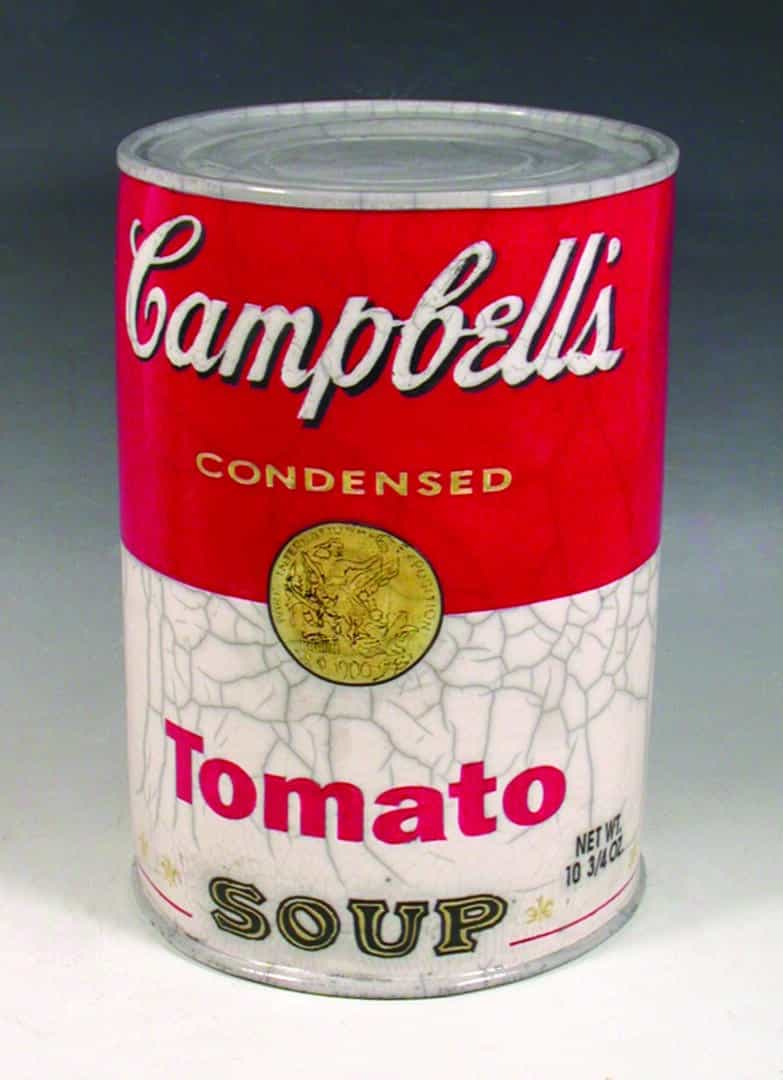

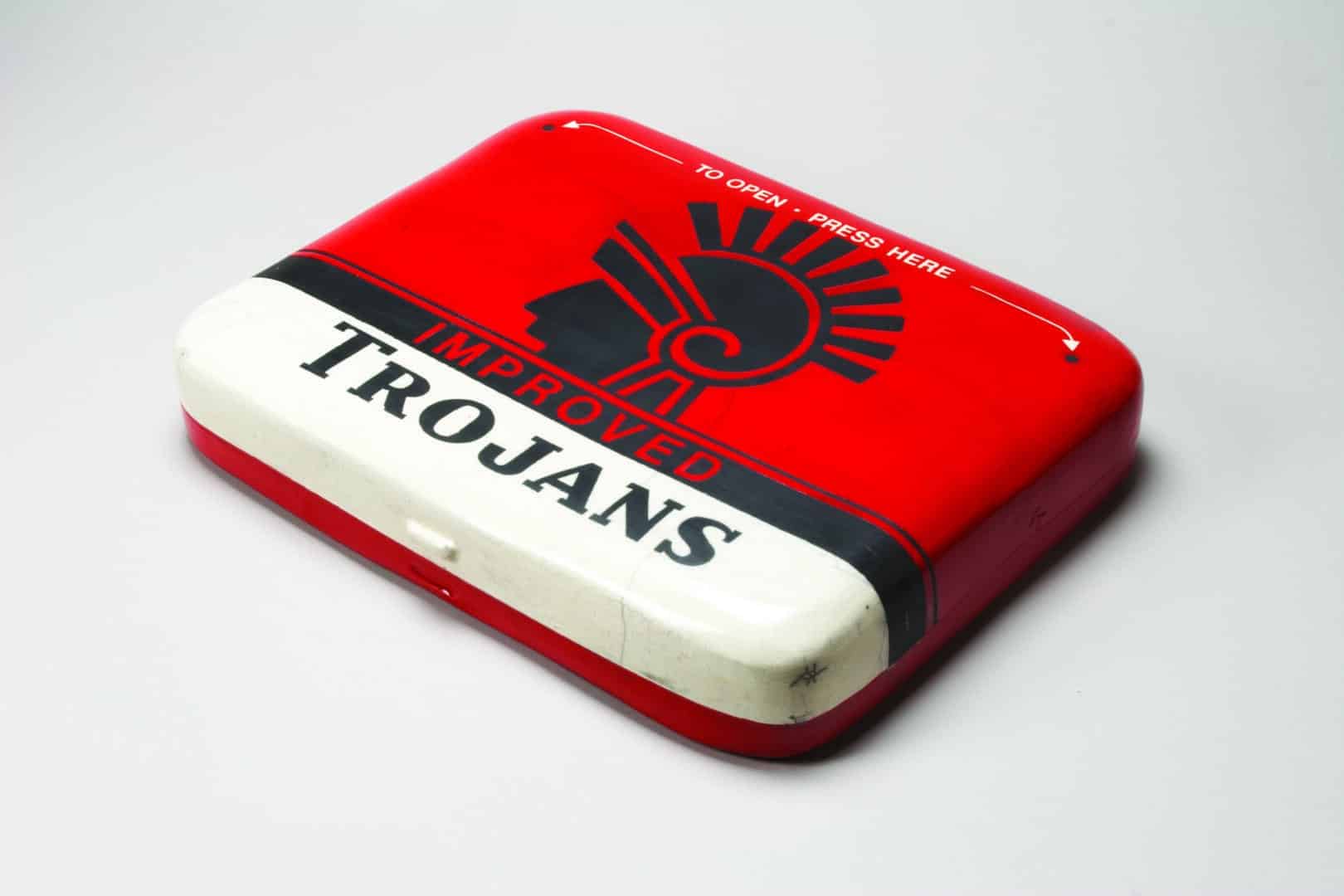

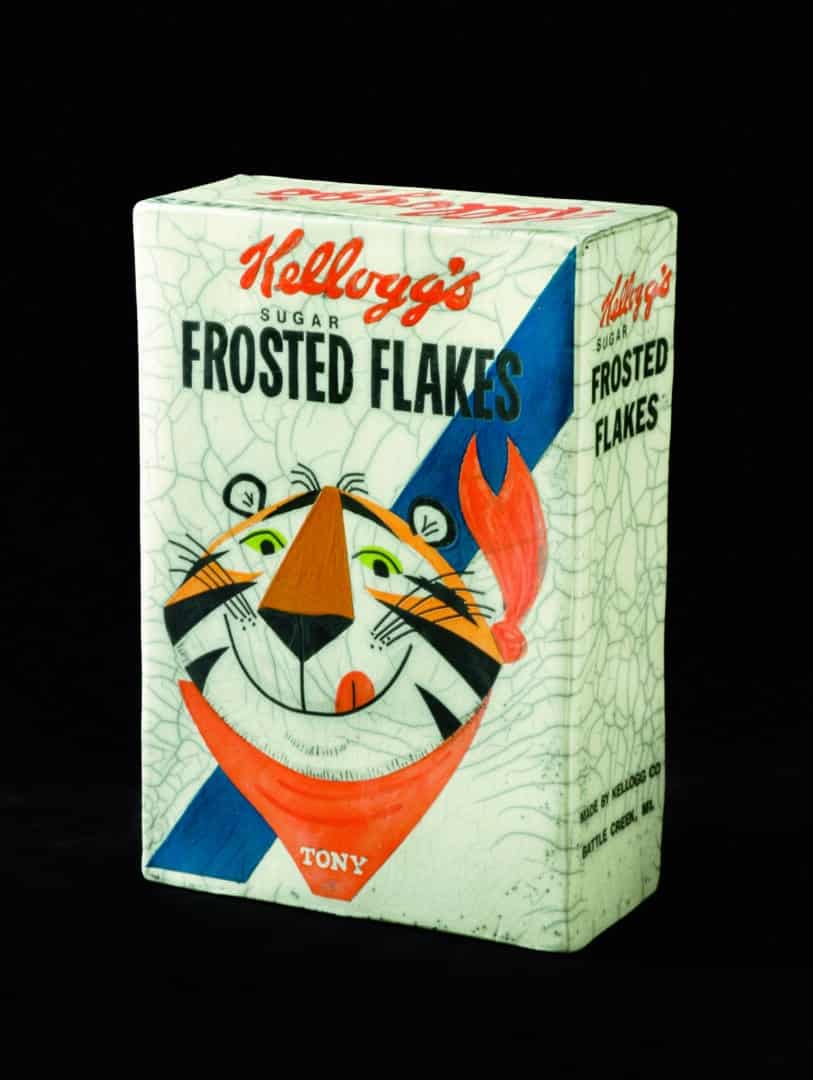

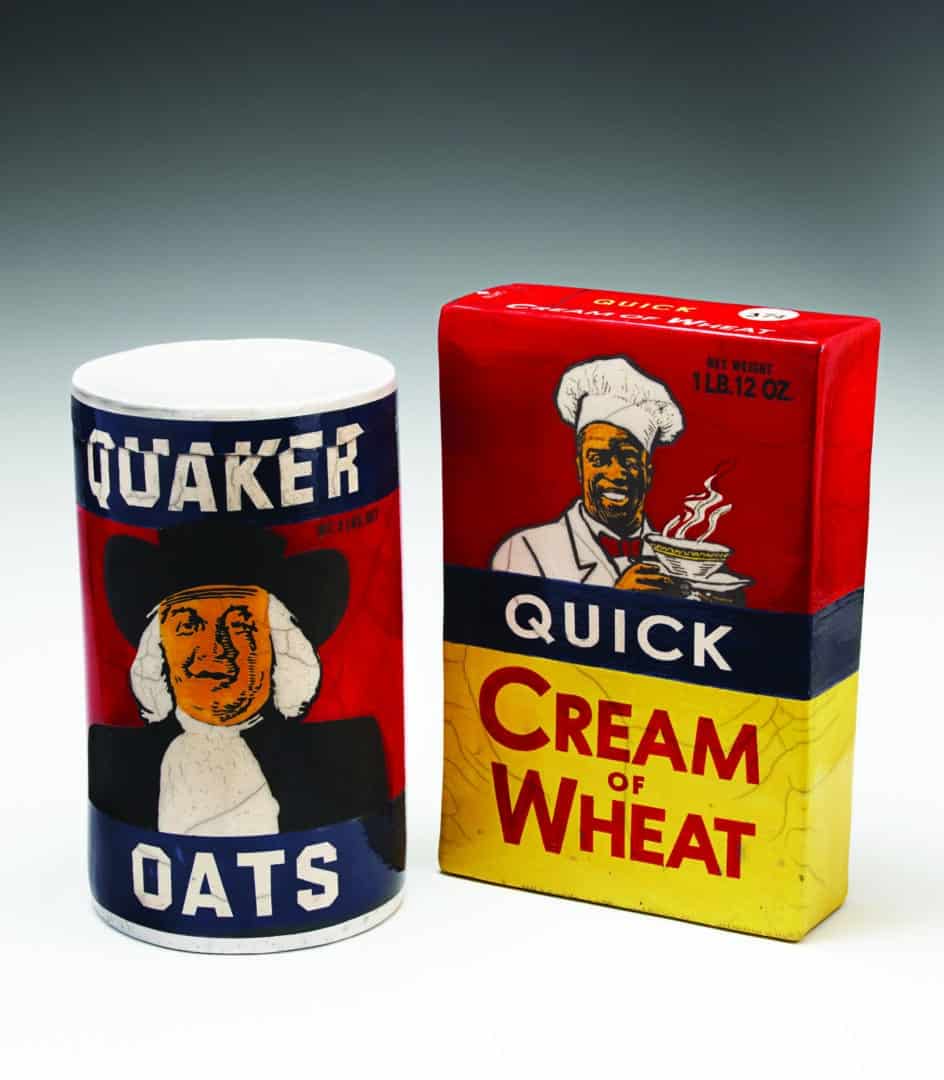

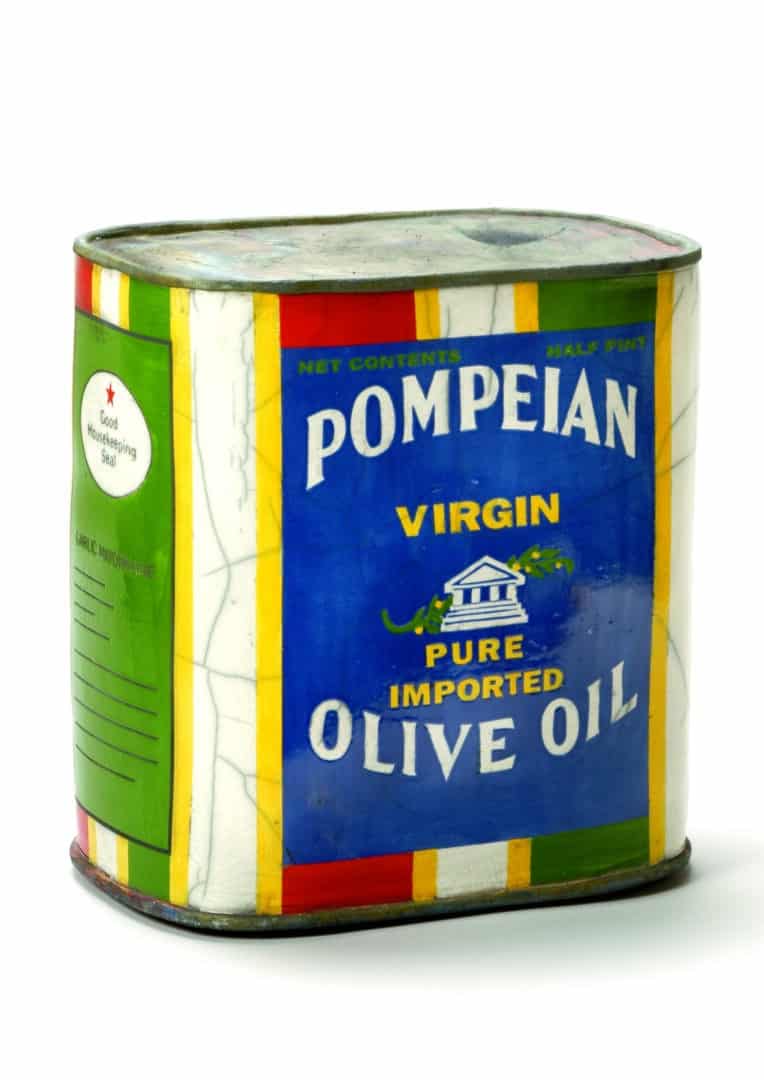

From ketchup bottles to mustard jars to Prozac pills, Karen is best known for her oversized ceramic sculpture of everyday products. She has made replicas of modern day products (Prozac pills and Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream are just two examples), but she prefers the older stuff. “The old packaging was beautiful graphic art. Now everything is plastic and ugly, and they all look the same. They are all blue, white and red. I specialize in the deco or the boomer era packaging. Package design was a real art form back then,” she says. The decision to “over-size” was inspired by an unlikely source – the 1970’s TV mega-hit Laugh In. “I always liked Lily Tomlin as the Edith Ann character sitting in the big chair. That always knocked me out! So I like things to be oversized. It started with big vegetables, and then I moved to boxes and products.” Her work appeals to people who may look to earlier decades with nostalgia, and while many fine artists might shy away from a description that involves any word like nostalgia, Shapiro isn’t one of them. “My work is a memory trigger. That’s what it is meant to be. The old packaging sets off that memory button, whether it’s a certain food or the old Revlon nail polish packaging, it makes people smile. I don’t take it seriously as art with a capitol “A” – I am a really fine craftsman. I don’t come up with these incredible concepts that fine artists do. I just make fun stuff, and happily people buy them,” she says with the confidence of an artist who sells as fast as she can make. Her best seller by far is the triumvirate of Heinz Ketchup, French’s Mustard and Best Food Mayonnaise – a sort of baby boomer sculptural still life that resonates with people of a certain age. Companies often hire Karen to recreate products for corporate offices or lobbies, and then there are the more quirky requests like the colorectal surgeon who wanted an oversized sculpture of Preparation H for his desk. “It’s hysterical,” Karen laughs. “People come up with some bizarre things that they want me to do, but it’s always fun.”

Karen’s personal route to her current artistic nirvana, was about as winding as Highway One through the redwoods. After majoring in design in college, she took an unexpected turn into the culinary arts after taking up gourmet cooking as a hobby. “The deal with my husband at the time was I would work while he went to law school, and when it was my turn I would get to do what I wanted. So we got divorced,” she laughs as she tells the story. But splitsville or not, he did hold up his end of the bargain by helping Karen attend culinary school in New York City and eventually set up her own pastry shop in Oakland. In fact, he has remained one of her closest friends and staunchest supporters. “We were married young, and we realized pretty quickly that we were not matched well at all,” she says. “We still loved each other but it wasn’t the right paring, but we never got to the hating part. He is still a dear friend and very supportive.” Karen ran her pastry shop for as long her bad back would hold out, but eventually the pain forced her to change course. She returned to the artistic arena but this time with the sensibilities of a person who spent thousands of hours rolling out dough.

“Actually, a lot of pastry chefs do work in clay because it’s very similar,” she laughs. “Instead of rolling out dough you are rolling out clay. A lot of the hand skills are the same.” So she enrolled in a ceramics class at the College of Marin and for the first time experienced the raku firing process – an event that changed her life.

“The first time I saw it (raku process) it scared the hell out of me!” Karen remembers. “I lived in Italy for three years, and I brought back all these espresso coffee pots because I love the shape of them. So I built one of those out of clay –oversized of course. And that was the first piece I ‘raku-ed.’ I went out to pull that thing out of the kiln, and it just terrified me. It is so hot! It’s like a blast furnace in your face. I remember thinking at the time –‘This is not for me.’ But I loved the results.” And she soon learned to love the rush of adrenaline, too.

The raku process dates back to 16th century Japan and is most often associated with beautiful ceramic tea bowls. In contemporary times, Western ceramicists, namely Paul Soldner in the 1970’s, have modified the process to compensate for the difference in atmosphere between wood-fired Japanese kilns and gas-fired American kilns. Karen has successfully blended traditional firing techniques with the raku process. She starts off with slabs of clay that sit for a couple of days until they reach the right consistency. She then molds the clay into different parts and then puts them all together to form her sculpture. The clay is allowed to dry and is then fired in an electric kiln for the first time. Graphics are applied next. Karen paints the piece with glaze, using the masking technique for lettering. She cuts out the letters in vinyl, applies them to the clay, puts glaze over the top and then peels the letters off. The “painting” process is meticulous and time-consuming. One piece can take an entire day. Then it’s back to the electric kiln for the second firing. And finally the piece is ready for the raku process.

“The first and second firing are done in electric kilns, and it takes eight to ten hours for those firings,” she explains. “The last firing is done in a small gas kiln and it takes an hour. So it’s very quick and very hot (1000 degrees Celsius). At the point where it’s ready, I pull the piece out of the hot kiln and the glaze starts to crack. I quickly put it into a reduction chamber, which is basically a garbage can with shredded paper in it. The piece bursts into flames. I put the cover on, which cuts off the oxygen and produces a reduction atmosphere. All the soot from the fire is sucked into the little cracks on the glaze. That’s how you get the crackling. If you see my pieces after the second firing they look kind of like plastic, but after the raku firing happens all those crackles happen and it funks it up. It makes it way more interesting. It magically transforms into something that is not shiny and new, but into something that feels old.”

The process can be risky, and over the years Karen has learned lessons the hard way. Cotton t-shirts are the only option because fake fibers – like polyester – melt, goggles protect expensive glasses, and good neighbors are a necessity when things get too hot to handle. Karen has had one close call. “I’ve had it blow up in my face once. Luckily my neighbor was home and could help. The burns were mild – like a bad sunburn – but it was scary. It’s dangerous, but I like it. It’s never boring. It’s always exciting to open the bucket when it’s cooled off. It’s a pretty violent process to the clay, too. I sometimes get breakage at the end of all of this. I have a ‘bone yard’ out in the back. It’s nice yard art.”

Once committed to ceramics and the raku process, success came quickly. Karen earned a coveted spot in a student show at the College of Marin. From there she took photographs of her work, made Xerox copies of the photographs and sent them off to Virginia Brier who was then the premier San Francisco gallery for her type of sculpture. Brier invited her into the gallery for a face-to-face meeting and asked Karen to bring samples of her work. “I was so excited,” Karen remembers. “I thought if I could get one piece into Virginia Brier’s gallery I would be thrilled, but she made me leave everything. She told me to go home and make more and by the time I got home she had already called to say they made sales!” Karen Shapiro’s art career was launched. Today she works with a handful of galleries. Limited by time and process, there is only so much art she can produce. A self-described workaholic, she already spends seven days a week in her studio. “There is only so much I can make,” she says. “I’m pretty maxed out right now. I can’t take unlimited galleries. So I’m lucky – I only deal with people that I like. All my gallery owners are my best friends.”

Karen moved up to Northern California a few years back. Actually she was forced to make a change after her rental home was sold and she was “tossed out.” A potter built her current home and it has that artistic feel. Originally, the studio was inside the house but the dust and soot got to be too much, and Karen remodeled, moving her studio into the garage. A state of the art kitchen now occupies the space where the in-home studio used to be, and her living space is home to an eclectic art collection including sculpture from ceramicist Tony Natsoulas, sculptor Patrick Amiot, photographer Roman Loranc, and one prized Lucienne Bloch photograph of Frido Kahlo. “I’m surrounded by wonderful art,” she says simply.

She still loves to cook and occasionally has friends over to enjoy her culinary skills, but for the most part Karen lives a solitary life. She sometimes travels to art openings, but even then she doesn’t like it. Karen thrives on the routine, and it’s the art that keeps her going. “Everyday I work until I can’t anymore, and then I’m on the couch with my four cats. They are my babies. They don’t talk back and they don’t bug me. I’m happily alone,” she laughs, and seems to genuinely mean it. With a bad back that leaves her with chronic pain, and now a pinched nerve, Shapiro admits to feeling the pressure of time. “My head is still twenty something, but the body is not. My work is very physical. I just keep hoping this old body will give me a lot more years because I would go totally nuts if I couldn’t work.” Shapiro does not work 24/7 in order to secure her artistic legacy. She is not driven by unbridled ambition. For this artist it is a simple equation; the art is like the air she breathes to live. If you are looking for deep meaning and metaphors in her art – subtle commentary on American consumerism perhaps – she won’t stop you, but it is not the motivation. It may be hard to believe in a world that expects art to come with intellectual pedigree, but in this case, Shapiro makes things that make her smile, and that also strike a chord with ordinary people. It really is that simple.