susan bennerstrom

written by kiera scholten

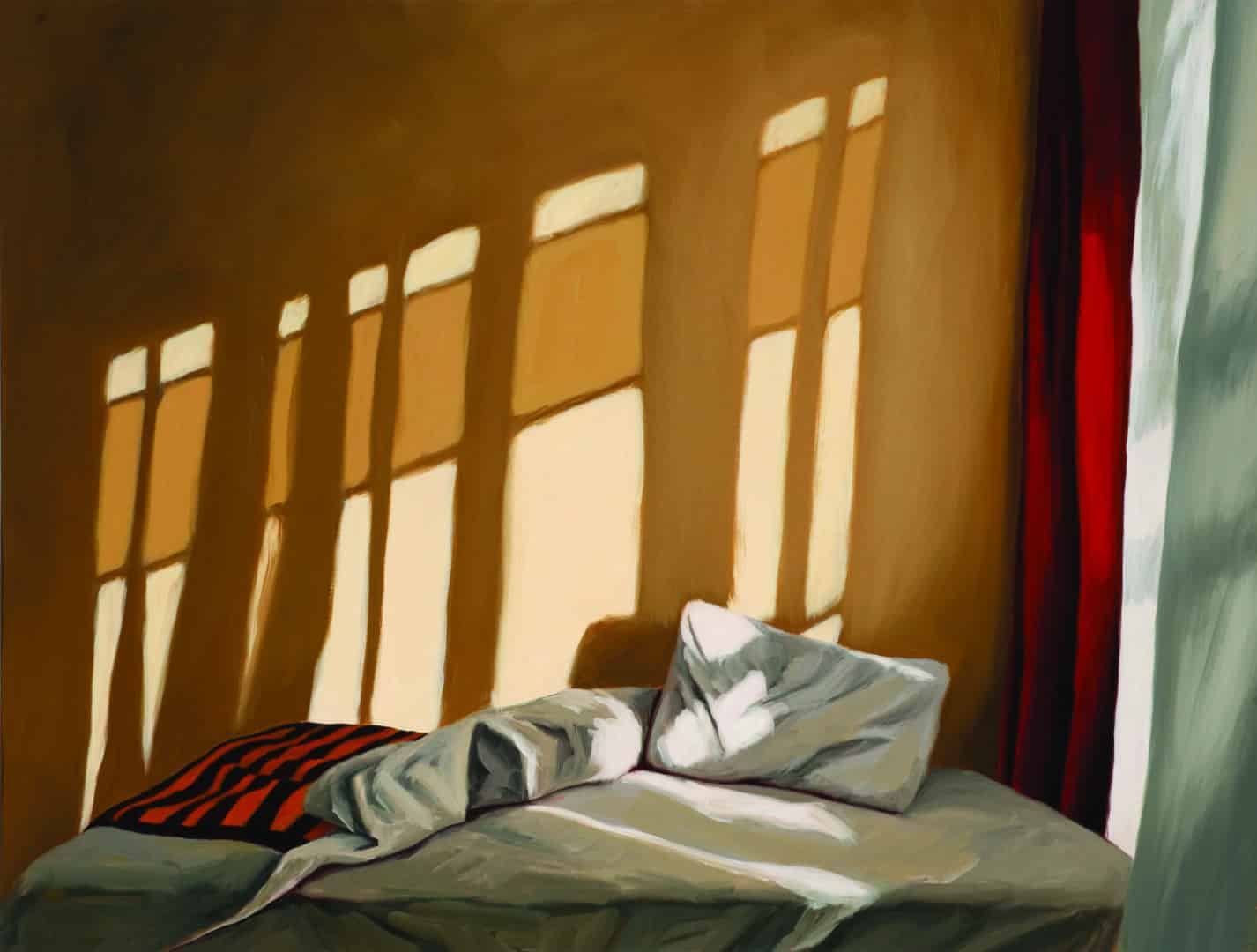

Susan Bennerstrom creates seemingly simple, still scenes—but they’re filled with movement. Behind the serenity, there’s a display of dynamic energy waiting to be unearthed. Luminous light permeates an empty room, casting ever-changing shadows as time clicks by. Sunlight bounces and reflects as it interacts with glimmering surfaces. An empty stairwell awaits someone to walk its shimmering steps. A cascading curtain blows in the breeze of an open window. Rumpled sheets and a light left on suggest someone left in a hurry, or will be back to bed soon.

These glowing interiors created with oil paints consume much of Bennerstrom’s work now; but of course, there’s been a lot of movement in her oeuvre as well. She always knew she was an artist, but what that looked like was a little less apparent. The life-long learner says her journey has been a continuous evolution—and it’s not over yet.

Bennerstrom’s parents were always supportive of her artistic endeavors. Her father was also of a creative nature; the owner of a furniture company, he designed the pieces himself. Her grandmother was even more artistically inclined and would often send her art sets as gifts. Art was in Bennerstrom’s blood. Thus, she knew at an early age she’d never consider another calling.

So Bennerstrom did what many fledgling artists do, and decided to go to college to study her chosen skill. She majored in art at Western Washington University, but after completing three years, needed a change. So she set out to see the sights of another continent. She calls her six-month European adventure “the best education.” She hitch-hiked across multiple countries with a friend, sleeping on streets, hostels, or wherever someone allowed them to stay. But the best part of the voyage was visiting museums in every city. She describes a “formative moment” at London’s Tate Museum when she walked into a roomful of Mark Rothkos. “Recognizing his commitment to a vision changed my life,” she recalls. “It was powerful.”

While her work has little in common with Rothko’s, the implied mood made an immense impression. But plenty of other European paintings had a profound impact on her technique—namely, those of the Italian Renaissance. Bennerstrom says this time period continues to be a huge influence, and it’s evident in her work. She utilizes rich, bold, earthy colors to create spaces where one can swim in the sunlight. Viewers can step into one of these sacred scenes in the same way they might wander into an Italian cathedral, falling to a hush as they revel in reverence.

Following her European jaunt, Bennerstrom returned to the States intending to finish college, but a marriage and a move altered plans. She spent the next five years in Berkeley, California. It might have been the experimental aura that was alive in 1970’s Northern California that drove Bennerstrom to try new things. It was here that she explored nearly every medium imaginable. Ceramics was first. “I wasn’t very good at it,” she admits. Next, it was weaving. “I was convinced I was going to be a clothing designer, making clothes out of my hand-woven fabrics. Then I realized I hated it.” After abandoning that, she also had some unsuccessful stints with basket making and photography before she finally pick up the brush again. “I always came back to painting,” Bennerstrom says fondly.

She continued creating after moving back to Bellingham, Washington (where she still lives), but also worked part time at the university library. It wasn’t until her mother passed away that she fully committed to her craft. “I realized life is short. This is what I need to be doing. This is what I really want to do.”

Even as she wholly pursued her passion, Bennerstrom never stayed stagnant; she always moved along the surface, as she does in life. At first she worked intensely with chalk pastels, creating abstract landscapes reminiscent of the rolling hills that dominate the drive between California and Washington State. These landscapes gradually gathered more detail, becoming more realistic in their representations. Soon distant buildings sprouted up on the hillsides. These structures eventually grew larger and larger as she got closer and closer—until she was inside.

It would be easy to come to rest in the warm ambiance of these interiors, but that’s not Bennerstrom’s nature. Even as the dust settled from her chalk pastels, she moved on. She began to feel as though she had taken her choice medium as far as she could. So she picked up oil pastels, which she stuck with for several years—but they also had their limits. That’s when Bennerstrom finally decided to take on the medium she had avoided for decades—oil painting. “I always loved how it looked,” she recalls, “but I was afraid of it. I thought once I started learning, it would take me the rest of my life to get any good at it.” That thought hasn’t changed, but she reached the point where she was ready for that challenge. Now she enjoys the fact that she can learn something for the rest of her life and never become bored.

Bennerstrom continues to be on the move. When not in her home studio, she spends free time racing canoes, riding bikes, or taking walks in breathtaking Bellingham. And while she loves living in Washington State, she doesn’t enjoy painting Northwest landscapes. She prefers colorful, open scenes to the ubiquitous green trees that hide the structure of this land. So any opportunity she gets, she’s jet-setting to some faraway place, armed with a camera to capture light in action. Her latest travel destination obsession is Turkey; before that it was Ireland. But a viewer might not recognize Turkish mosques or neo-Gothic windows in her work. She wants the focus to be on the light in these spaces, as opposed to the spaces themselves. So why does she trot the globe just to take pictures of light? “Well, because I want to,” she says with a twinkle in her eye. Good enough.

Whether her paintings depict lonely landscapes, moody cities, or ambient interiors—all exude mystery. What’s missing is as important as what’s present. “You’re very aware of the absence of humanity,” Bennerstrom says of her work. “There’s a human charge—a feeling that there were people there recently, or will be soon.” Bennerstrom says much of her work is narrative and metaphorical, but often even she is unaware of the exact meaning. Even when she does know, she doesn’t offer overt signs. It’s part of the reason she leaves out human figures—especially faces. She doesn’t want to “spill the beans” or tell the viewer what to think. She wants viewers to effortlessly insert themselves into the piece. So Bennerstrom opens a door or a window and sheds some light, so we might bask in the warmth and become illuminated.