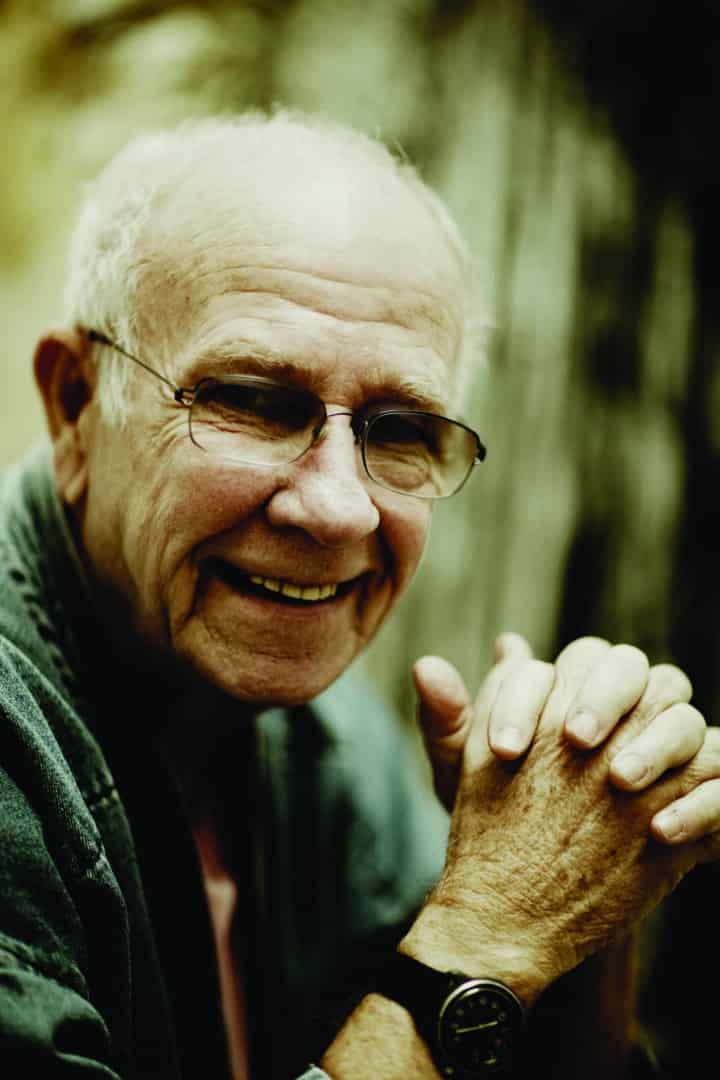

THE ANGLES OF JOE GOOD

Written by: ERIN CLARK

Photography by: PRAKASH SHROFF

For Los Angeles artist Joe Goode so many pivotal moments were unforeseen – so much influenced by the unpredictable: a snowstorm, a fire, a hellish commute, bottles left by the milkman on a doorstep, an opportune meeting with a new gallery owner, and even a childhood friendship. All of these seemingly innocuous things leading to monumental change for an artist who has always maintained that making art is a choice. “When you don’t make any money, that’s when the real decision comes,” says Goode. “Do you really want to be an artist, or do you want to be successful monetarily. If you want the money, it’s better to go sell real estate.”For Goode, his first test of commitment may have come on a Los Angeles Freeway. Commuting between Los Angeles and Box Canyon, famous only as home, for a time, to Charles Manson and his murderous gang, it took Joe as long as three hours to get to classes at Chouinard Art Institute in downtown L.A. He would leave the house at 5 o’clock in the morning and return late at night, often balancing groceries precariously on his motorbike. He was exhausted all of the time. “I moved out to this place in Box Canyon because an instructor offered it rent free – kind of like house sitting, but it was December and it’s raining, and I have a wife and one year old baby to support. It was a terrible personal time – the worst time of my life,” he says. But he kept working. Ultimately, the marriage didn’t last and Goode was soon out of Box Canyon, but the commitment to the creative, despite whatever hardships he might encounter, took hold. However difficult, however inconvenient, however inhospitable life might be or become, he was, for better or worse, an artist, destined to create a “new way of looking at things.”

The decision to come to California, which decided his artistic path, was made late one night while sitting in a car in Oklahoma City. A year out of high school and drifting, Goode was ready for art school but he couldn’t decide between New York and Los Angeles. Childhood friend Ed Ruscha was already in Southern California, and another artist buddy, photographer Jerry McMillan, was there, too. McMillan was home for the holidays, and after a night out the two old friends sat in a car outside of Goode’s house talking about where Goode should go. McMillian was pushing for California, but Goode wasn’t sure. After two hours, Joe opened the car door to leave only to discover a storm had kicked up, the wind was howling and a foot of new snow was on the ground. Joe looked back at his friend and said, “I’m coming to California.”Goode sold his 1955 Ford Fairlane, bought an airplane ticket, and headed to Los Angeles. “It was the first time I was on an airplane,” he remembers. “I flew in at night, and I don’t mind telling you, I was terrified. I saw all those lights and wondered how I was ever going to find anyone. I was supposed to stay with Ed (Ruscha), but I had no idea how to get there. I think I finally called someone to come pick me up. I was scared but going to California was as much about freedom as it was art.”

Goode immediately enrolled at Chouinard Art Institute and started taking classes, but realized early on he wouldn’t be staying for all four years. Money was an issue. Goode was working three jobs to support himself and pay for tuition, and he knew he couldn’t keep it up, so he took classes he was really interested in, including an advanced course with instructor Bob Irwin. “I think he was the biggest influence on Southern California art at that time,” Goode says bluntly. “Not just because of his art or the artists he associated with, but because so many people were influenced by him. He was a great teacher, and the best part about him was he never told you what to do. He always emphasized that you should do something you WANT to do.” The encouragement was exactly what Goode needed, but even with the high praise for Irwin and other instructors at the school, Goode insists he learned the most from his fellow students. “When I was concerned about something at two o’clock in the morning, who was I going to call? He asks rhetorically. “I wasn’t going to call an instructor. I was going to call another artist. That’s how we learned. We all had studios near each other and we depended on each other.” Today the list of Goode’s artists friend reads like a who’s who of Southern California art: Ed Ruscha, Billy Al Bengston, Ed Moses, Larry Bell, and Eddie Bereal, just to name a few, but back then they were just buddies helping each other out.Goode got his first show right out of school. An instructor sent him to the Huysman Gallery where he met with Henry Hopkins, who was establishing himself as a force in the L.A. scene. Hopkins took a look at a few of Goode’s drawings, and then asked if he’d like to have a show, and did he know any other artists who might be interested? “My heart was pounding right out of my chest,” Joe remembers. “I’m thinking, ‘Whoa, that’s all there is to this?’ It was too easy.” Joe quickly gave Hopkins a list of his artist friends and the “War Babies” show was born. It was a first show for Joe, his good friend Ed Ruscha and others. The Huysman Gallery was on La Cienega, right across the street from the better-known Ferus Gallery. Both galleries showed a number of the same artists, but Goode was never included in a Ferus show. Although well aware of the gallery’s reputation, Goode rejects the idea that Ferus was the only influential gallery in Los Angeles at the time. “The best dealer in town was Nick Wilder,” he says. “Nick was on par with Walter Hopps (Ferus Gallery). Look at the artist list at a Nick Wilder show and it was every bit as impressive as a Ferus show.”

It was a competitive time in the Los Angeles art scene, and Goode, with a well earned reputation as opinionated when it came to dealers or gallery owners who he thought were unfair or prejudiced against his art, didn’t always get the show or the recognition as some of his counterparts. His good friend Ed Ruscha did, and over the years, Ruscha has become the better known of the two, but Goode insists they have never been competitive. “We’ve known each other since we were seven years old,” he says. “Sometimes we even travel over the same subject matter, but if you are really following what you know and what you see, why is that surprising? We both have seen the color of the sky in Oklahoma or the kinds of houses in Oklahoma. I have done paintings of houses and he has too, but they are not the same at all. He’s done skies and I’ve done skies. I’ve done glasses and spoons, and he has done drinking glasses, but done totally differently. We are just not competitive. Never have been.”Although developing diverging styles, both artists were at the center of the burgeoning Pop Art Movement in Southern California. The two, along with Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and Wayne Thiebaud were included in a landmark exhibition at the Pasadena Art Museum titled “New Paintings of Common Objects” – a description Goode much prefers over “Pop Art.” Trying to find context to his life and his art, Goode made a conscious decision to paint what was in front of him – to paint what he knew. His work wasn’t political or statement oriented; instead he was looking for personal images that he could show in a new way.

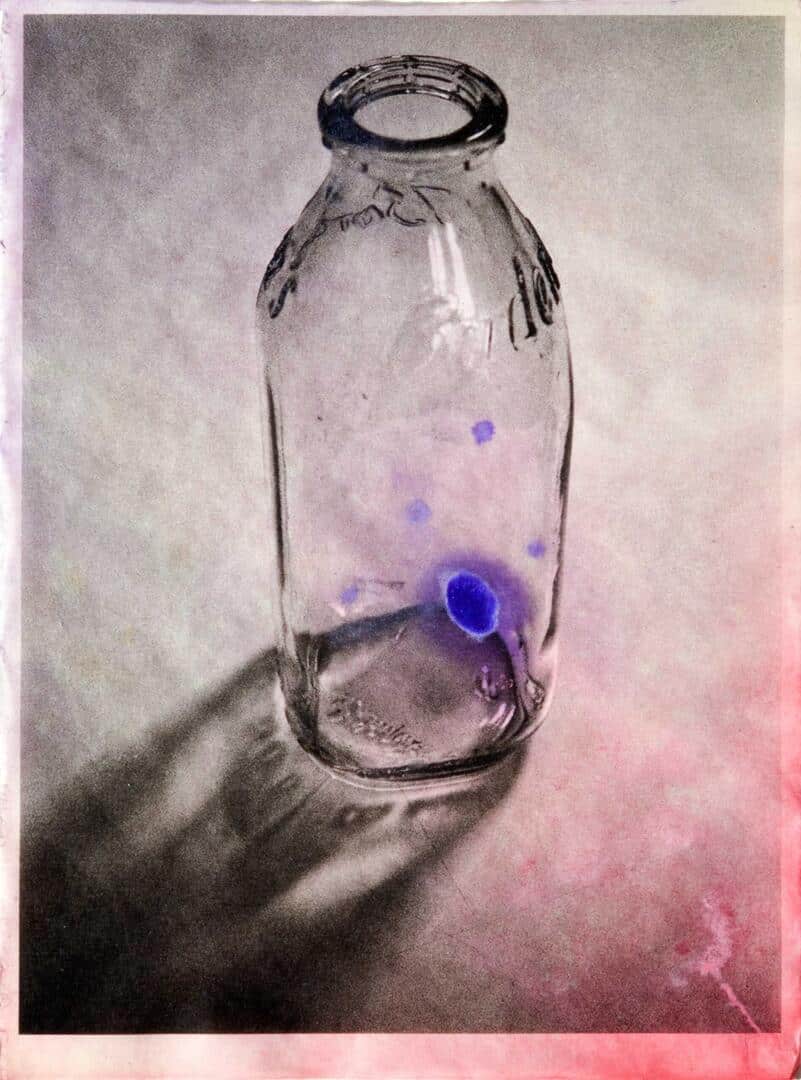

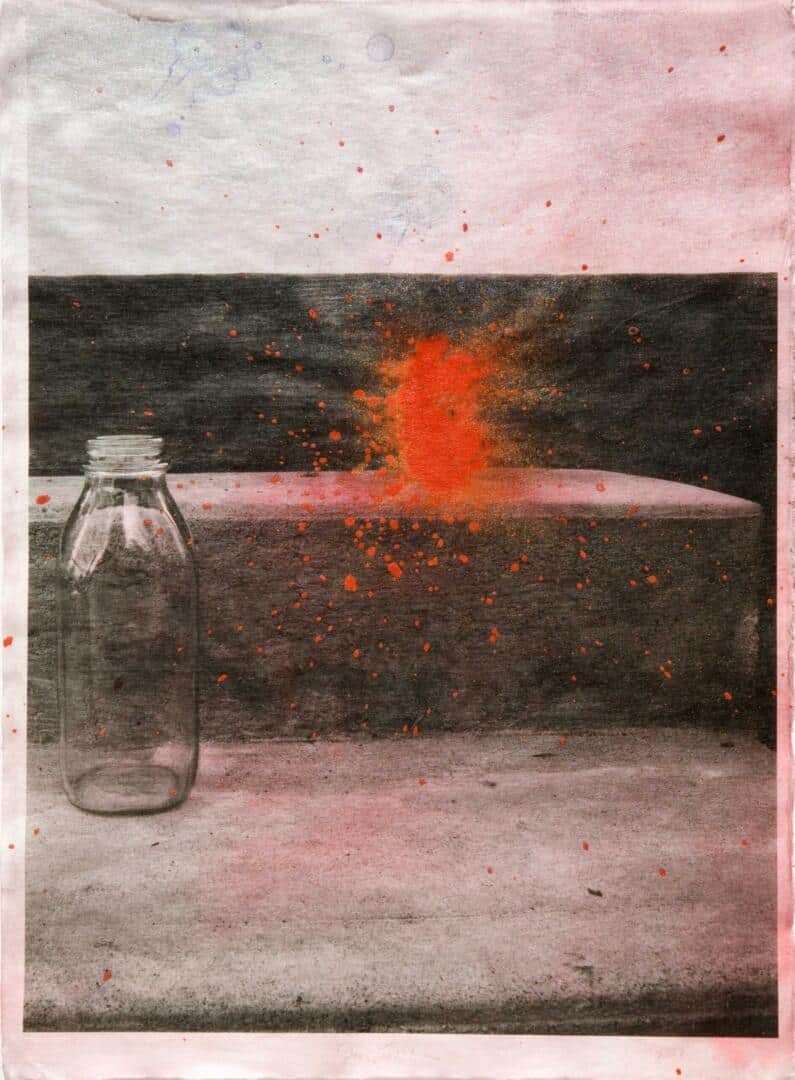

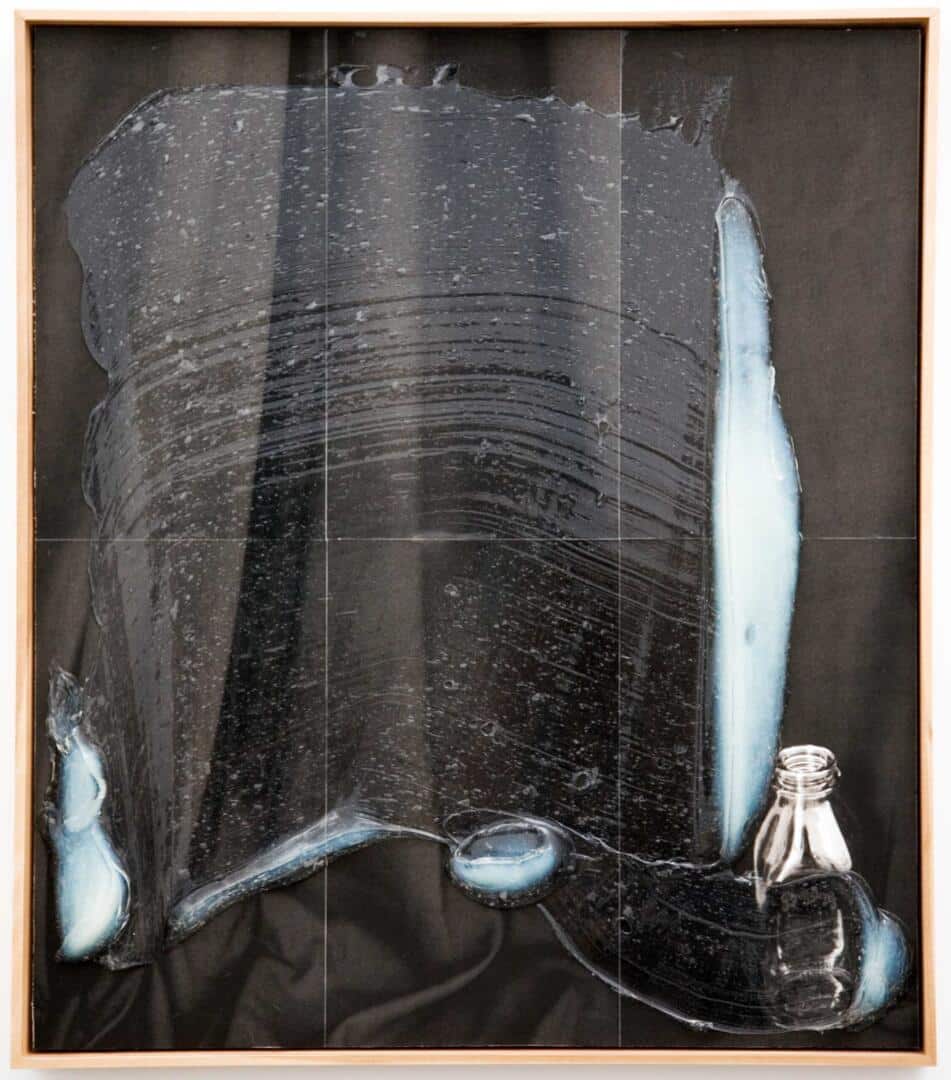

Goode began to play with perception. One evening he returned home and noticed milk bottles on the stoop. A simple everyday object that became the genesis for his first critically acclaimed series, known as the “Milk Bottle Paintings.” They were large-scale monochromatic canvases with a milk bottle, painted in similar hues, placed in front of the canvas seemingly ripped from the image. The resulting work created a representational, abstract blend that was perfect for the Pop Art Movement taking hold in Los Angeles in the early 1960’s. There was nothing calculated about the series. Joe was simply painting what he knew and what he saw.The Milk Bottle Paintings, with their visual three-dimensionality came first, followed by a series of house paintings, where the artist drew, in line form, stereotypical suburban houses in the middle of the canvas and surrounded them with monochromatic fields of color. The paintings pull the viewer into a vortex that feels familiar (we all know those houses) and a little suffocating at the same time. At this point it would be easy to speculate about the artist’s feeling on suburbia or a traditional childhood in Oklahoma and all of the expectations that go with that, but Goode says don’t bother. “There is no psychological or literary meaning. It’s just visual,” he says bluntly.If there is a common thread to Joe’s work through the years, it would be the concept of “looking through,” which admittedly didn’t even gel for the artist until subsequent series on staircases and windows. In the case of the latter, Goode painted the sky as the wall with the window in the center of the canvas, turning the usual visual inside out, so to speak. Goode provided more intrigue with the Staircase Series. With these installation pieces, which are more sculpture than anything, Goode takes us up and down, and through – where it actually goes, however, is entirely up to the imagination.

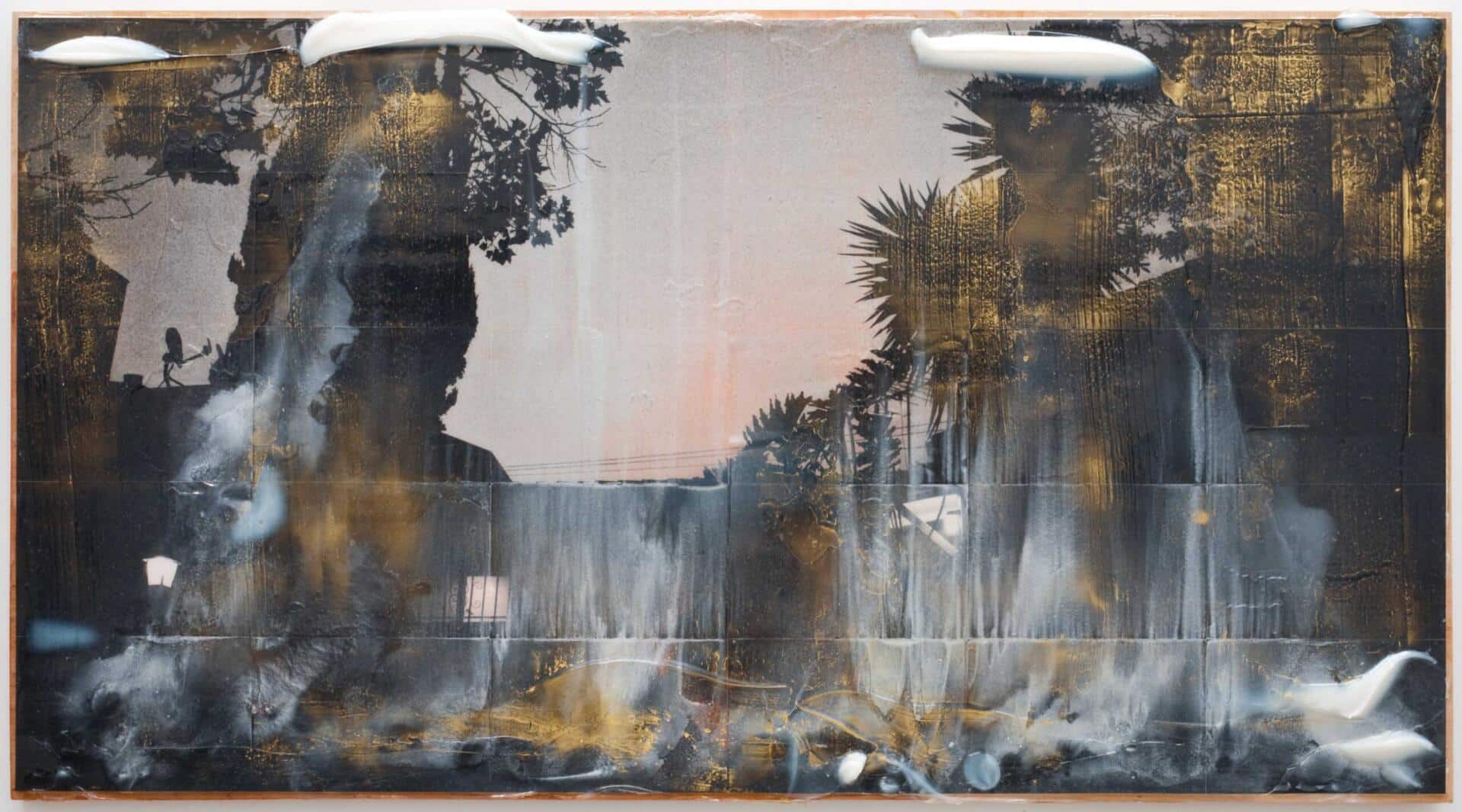

In the early to mid-1970’s, Joe moved to a small town in the Sierra foothills – a cultural seismic shift if there ever was one. Nothing really dramatic forced the move from L.A.; Joe just wanted a change of scenery. “I didn’t go away mad,” he laughs. Small town life was different, but soon enough residents of Springville embraced the artist from L.A., and in return he became part of the community, even designing a couple of posters for the local rodeo. His own work stayed true to form in the sense that Joe painted what he saw around him: trees, waterfalls, clouds and forest fires, but always with a perceptual twist. Cloud canvases were ripped to reveal layers underneath, a shotgun fired at a painting created intriguing patterns of destruction that exposed color underneath, and forest fire paintings were singed with a blow torch – whatever the tool, whatever the process, the point was to alter perception, to encourage “looking through” as opposed to “looking at.” Construction and deconstruction became part of his lexicon – and eerily prophetic.“Moving back” to Los Angeles is misleading, because Joe never really left. He may have lived in Springville, but he always maintained a studio in the city. Los Angeles as a place and as a point of view is in his blood. “I like L.A.,” he says with typical understatement. “I like almost everything about it, except the traffic. I like that you can be an artist here and work in relative privacy. ”If I didn’t live in L.A., I’d live in Japan – it’s the most beautiful place I’ve ever seen.” The first time Goode went to Japan he traveled by private plane. The owner, collector Fred Weisman, had commissioned Ed Ruscha to paint the outside, and Joe to paint the inside. “I painted a sky the entire length of the ceiling. The sunrise was at the back and the sunset was at the front. Ed painted the outside,” says Goode. It’s probably safe to assume that with Ruscha and Goode in charge, the work was compelling, but it was eventually destroyed when the then Los Angeles Rams bought the plane and had it repainted. “They had to do it – it was in the contract. Only Fred could own the ‘paintings.’ Ed thought of that,” Goode remembers with a chuckle.The Japan trip made an impression and Goode has been back many times, and exhibited there often over the years. And although they met in the United States, his wife, Hiromi Katayama, is Japanese. The idea of moving to Japan maybe appealing, but it’s probably not going to happen. Goode is part of the Southern California landscape, even more so after a frightening night in May of 2005.

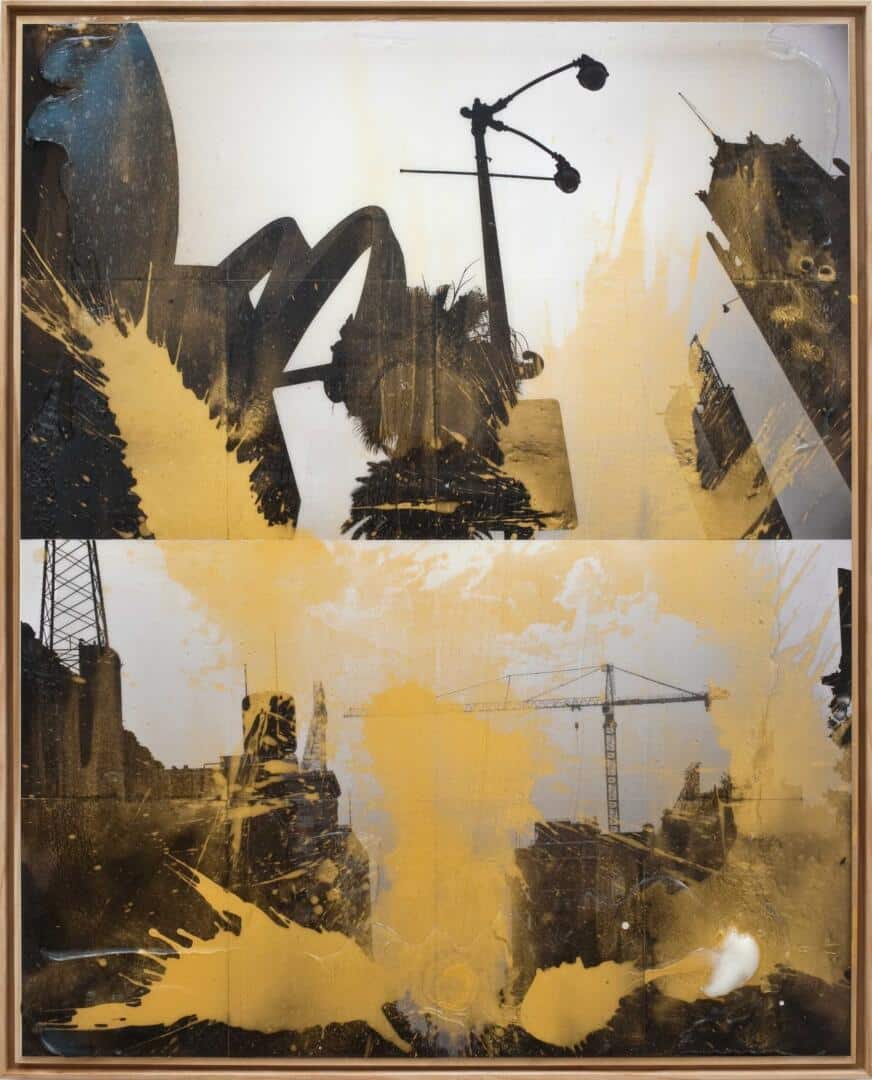

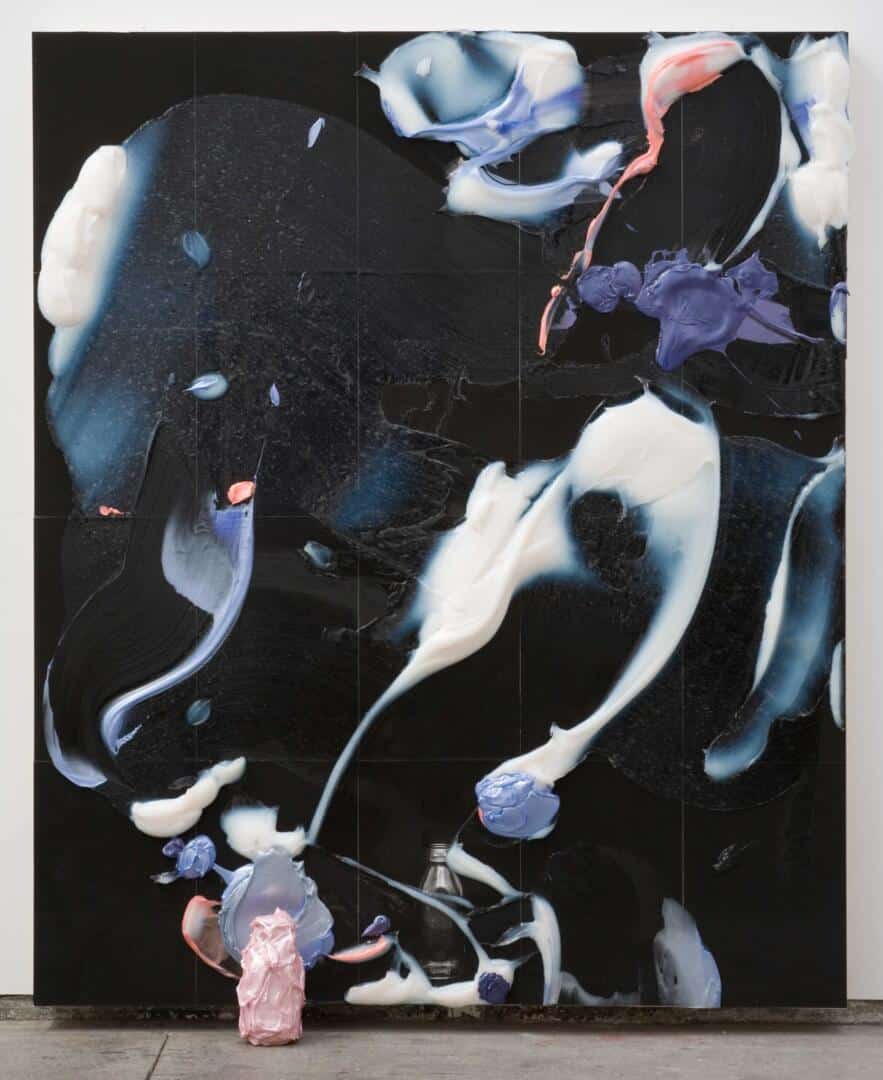

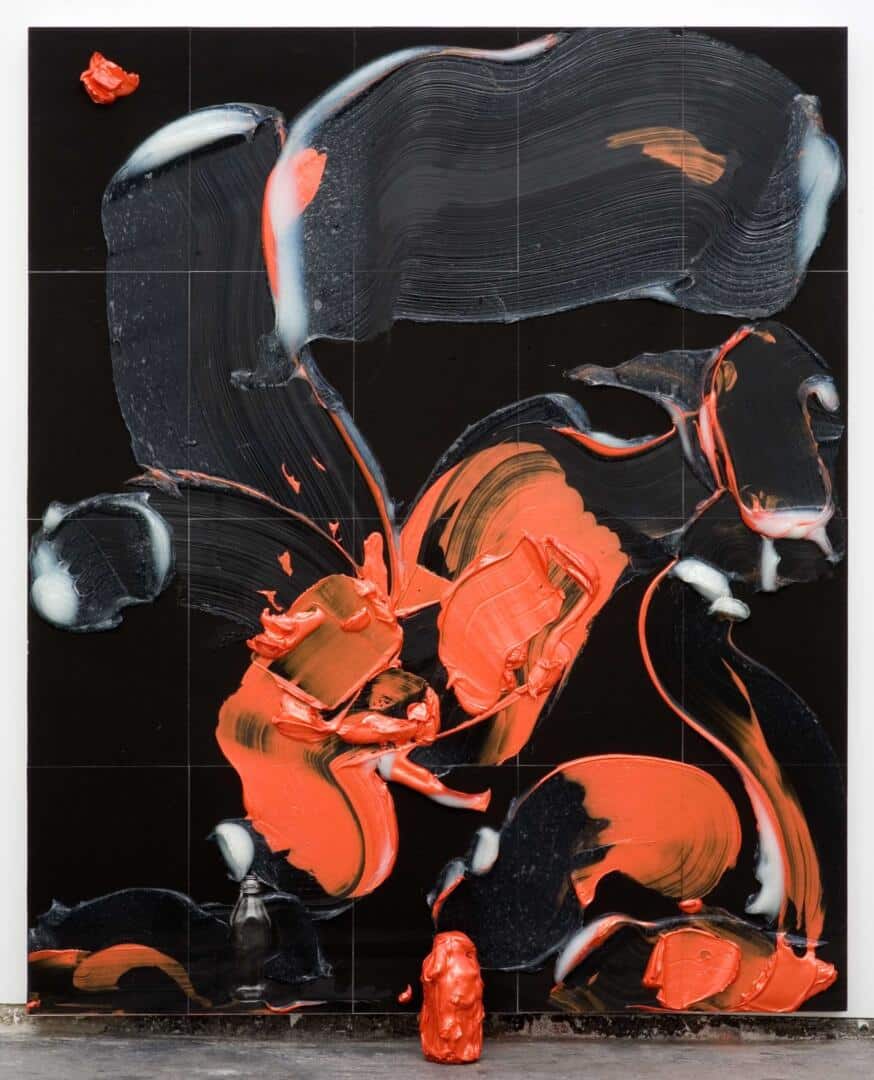

Goode was jolted awake at five o’clock in the morning by his dog, Pollock, barking loudly. Pollock wouldn’t give up until Joe got up. He stumbled outside to see what the fuss was about and he couldn’t believe it – his studio was on fire. Smoke billowed out of the building. Fire investigators said “spontaneous combustion of oily rags” was to blame. Joe lost much of his own work that night, and, even more upsetting, many paintings he traded with friends like Ed Ruscha, Kenneth Price, Larry Bell and Ed Moses. It was devastating, but five years later he has perspective. “It wasn’t like the people who lose everything in a forest fire. I didn’t lose everything. No one was injured. I lost a lot of paintings and that hurt, particularly the paintings of other artists’ work. Those are things you can’t get back. I was in shock, but then all these people came to help me. Within two hours, the whole conservation department from the county museum came over. They were pulling stuff out, trying to save what they could like those paintings in my studio,” he says referring to three ripped cloud paintings rescued from the ashes now propped up against a wall in his studio. “You know, the fire happened and I had prostate cancer two years prior to that, and I realized there isn’t much time to wait around and worry about what someone else might think or what it might mean.” Joe took that revelation to heart and got busy.He found inspiration in the ashes by first photographing the devastation and then incorporating the images into new pieces. He painted over the photographs, added other images from other painting periods and developed a new body of work. Like the regeneration that happens after a forest fire, Joe’s new vision took root. There were easy to see differences like acrylic paint instead of oil, and harder to articulate but no less profound changes like freedom from constraints, self-imposed and otherwise. “I have always painted in series,” he says, “but this kind of blew the lid off that and I realized I can make one if I want or I can make fifty. I don’t have to make this in serial context. The fire took me back to basics. I always want to make something I haven’t seen before. Or see something in a new way. That has been my criteria all along.”

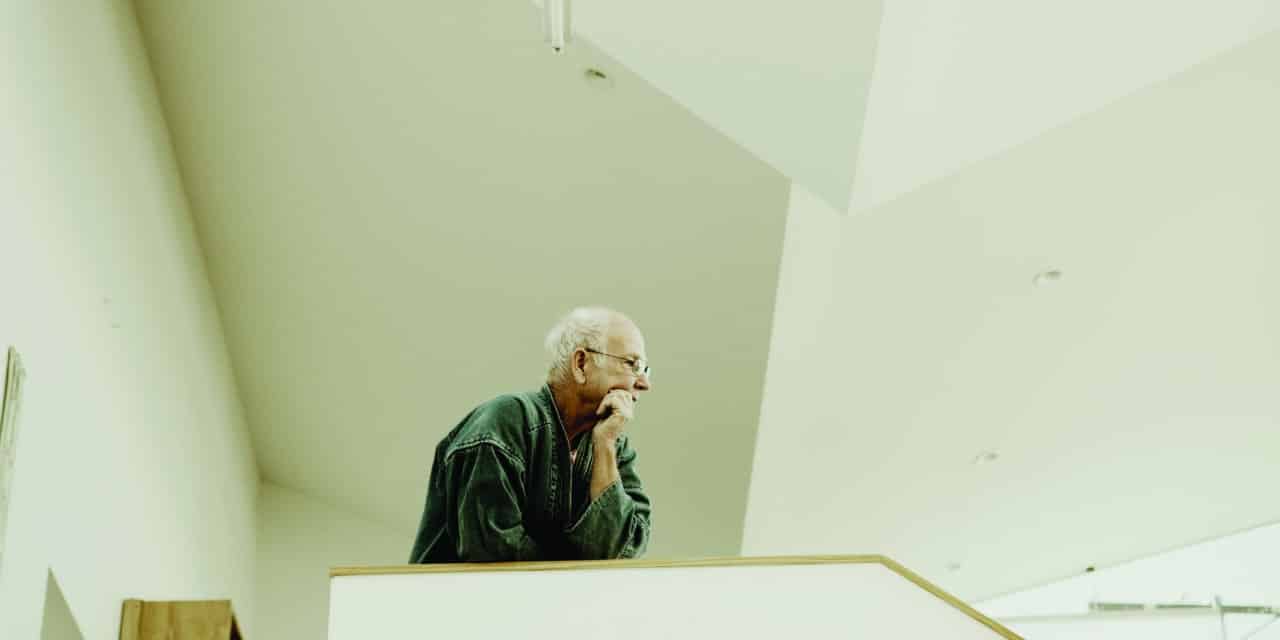

Today Joe’s rebuilt studio – a large open space with soaring ceilings – is filled with images from his past incorporated into new work that feels as contemporary as the Milk Bottle pieces did fifty years ago. On every wall there is a piece that tugs at the memory; a six foot long commissioned piece for the new W Hotel in downtown L.A. incorporates photography, painting, and even some tearing of the canvas. Milk bottle images are prominent in another mixed media piece, a staircase winds through yet another canvas, and clear glass milk bottles, drenched with an epoxy substance that transforms them from everyday objects to pieces of sculpture, fill ledges and shelves throughout the studio. With paint splattered Vans on his feet and a professorial sweater hanging loosely, Joe looks exceedingly comfortable in his new space. This is where he spends most of time melding his past with his future. He isn’t regurgitating or rehashing ideas. There is palpable excitement about the work, and from the artist. It seems his life and his art have come full circle. He smiles and says, “It always does – if you last long enough.” No problem there, Joe Goode is making good on his promise to make every minute count.