Norman Rockwell Goes Gonzo

By J. Michael Welton

Bob Trotman’s artistic vision of the world is based on a childish desire to upset the apple cart.

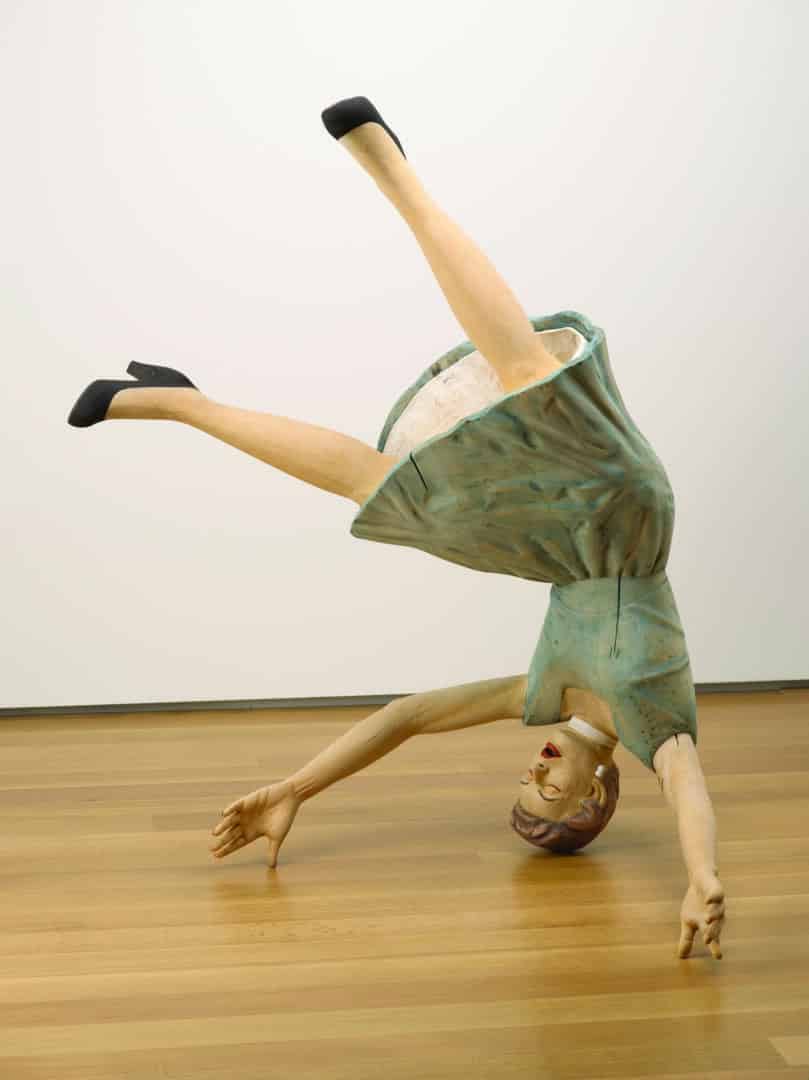

His sculptures depict well-dressed model citizens, apparently plucked from the corporate world and frozen in devastatingly off-balance positions. Some appear to be diving. Others, arms and legs akimbo, tumble upside-down. Still others careen through mid-air, clearly terrified.

Almost all seem to be tragic victims of an unstable, unpredictable world that’s hopelessly beyond their control.

“He’s saying that life might seem perfect, but underneath there’s turmoil, flux and change,” said Linda Dougherty, chief curator of contemporary art at the North Carolina Museum of Art (NCMA). “Don’t be too satisfied or too certain, he’s saying, because at any moment you can lose your moorings and the ground can shift. There’s this idea that a sense of stability is false.”

“Inverted Utopias,” an exhibit of his work, opened in the East Wing of the NCMA in November. It’s scheduled for display through March 27, 2011. In the same building, occupying a neighboring gallery and running concurrently, is a Norman Rockwell show. They’re a pair of gifted artists, but the two are polar opposites when it comes to their views of American culture.

“I’m trying to present a wooden world to the viewer that’s something like Norman Rockwell, but with a large dose of Karl Marx and Franz Kafka,” the artist said. “I’m not a big admirer of Rockwell. He said he portrayed life as he wished it were – his view of life is much more sweetened than the real thing.”

While all chains of authority are clearly in place with Rockwell’s work, Trotman wants to present a populist vocabulary and commentary. “Rockwell endorsed institutional values,” he said. “My view is to criticize them. I want to poke holes in those Norman Rockwell images we grew up with, and expose the mechanism of the springs of power.”

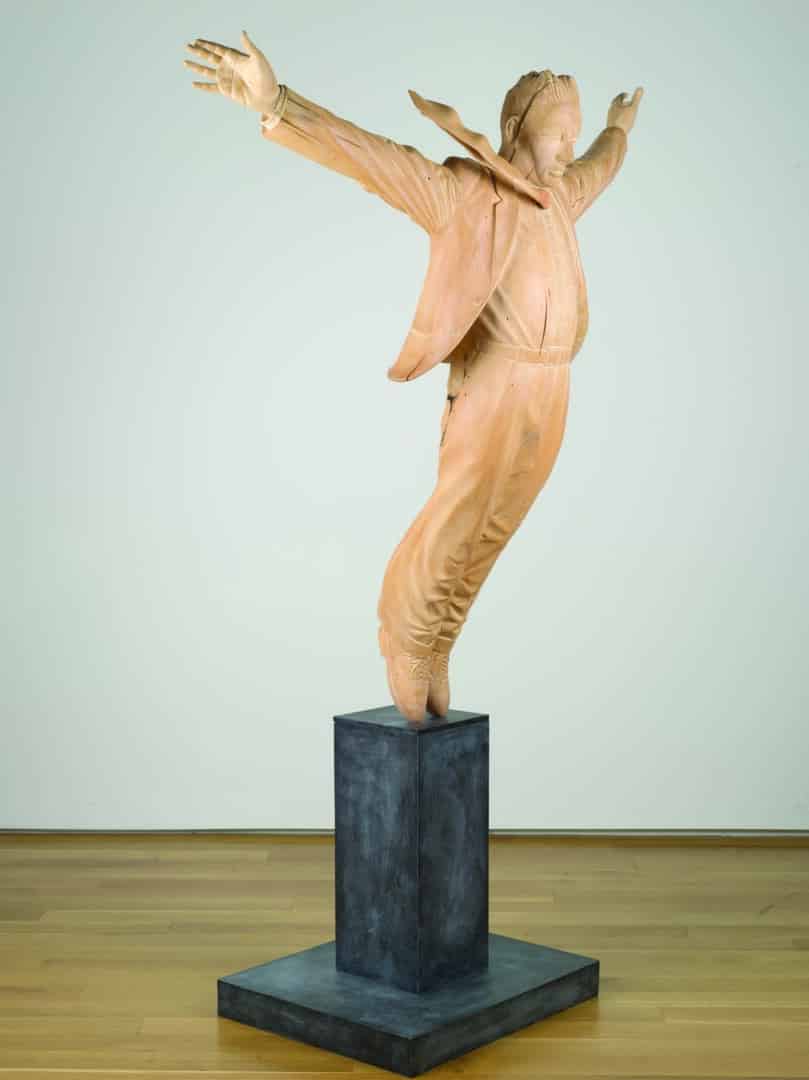

The oldest piece in his show is “Swan Dive,” created in 2000 and on loan from the Sydney and Frances Lewis Collection. It recalls the graceful, forward-thrusting sculptures once attached to the prows of sailing ships. But it’s hard to tell if its subject, a well-dressed man, is leaning windward like a hood ornament to take in the view below him – or if he’s about to leap into the unknown from a very tall, highly precarious place. Then again, Trotman surmises, he might be thinking about jumping off the pedestal of masculine conformity.

“A Charlotte art critic called my work ‘figureheads on a clipper ship bound for purgatory,’” the artist said. “But really, it has to do with power, and pulling the rug out from people who might occupy positions of power. It’s fun for me to see them slip on a banana peel – to see the humor and the joke in re-contextualization, to see things in a different order.”

Just as Aspen author Hunter S. Thompson staked out the death of the American Dream for his own professional beat, this gonzo artist from the foothills of North Carolina calls for an examination of the profit motive that drives the nation’s corporate culture.

Those who own his work offer him secret confessions. One corporate manager admitted to upsetting his superiors or committing some other unknown sin at work, only to find himself banished to a miserable life on the road, miles away from his former office. “A lot of the sculptures are owned by the people I’m making fun of,” Trotman said. “Secretly, they’re laughing, but they won’t comment in public because they don’t know what the board of directors might do.”

He grew up in the 1950s and ‘60s in Winston-Salem, the son of a distant, authoritarian father and a Junior League mother. It was a traditional, conservative time and circumstance. He’s still rebelling and still trying to understand those times.

“The world I grew up in seemed very stable,” he said. “But to see now what a complete illusion that was … to understand that America is not always going to be number one in the world, that everything’s up for grabs at any moment … to understand all that is to understand that the world is too complicated to predict.”

Thus the galleries full of people, sculpted from linden and poplar, who look as lifelike as Rockwell’s paintings down the hall, but who appear to have been victimized by some startling kind of intervention, through an unknown, most unsettling series of circumstances.

The inversions are, in fact, conduits to Trotman’s childhood – a way for the artist to access his subconscious and his inner child. As it happens, that child is a mischievous lad, a kind of minor-league juvenile delinquent who delights in standing people on their heads. He’s an Eddie Haskell who’d like nothing more than to snicker behind June Cleaver’s back on her very worst day.

“The cataclysms are a way in,” he said. “They’re a cavalcade of calamities, like circus performers doing pratfalls. They’re about things from childhood that I don’t fully understand. It’s a very rich place for me to go to and draw on – a good place for material.”

In one gallery known as “The Hours,” a parade of characters tells its tales one by one, their near-tortured faces bearing mute witness to internal and external traumas that visibly wrench them emotionally.

Adorned in an apron and brown dress, the Cake Lady kneels, smiling, and proffers a chocolate cake proudly to her unseen master.

But there’s a crack in her head.

“She’s tried to make it for her husband several times, but it doesn’t turn out,” Trotman surmised. “She’s part of the middle class corporate world, but she doesn’t see her reason for being. She’s not as happy as she thinks she is – that’s a mask she’s wearing.”

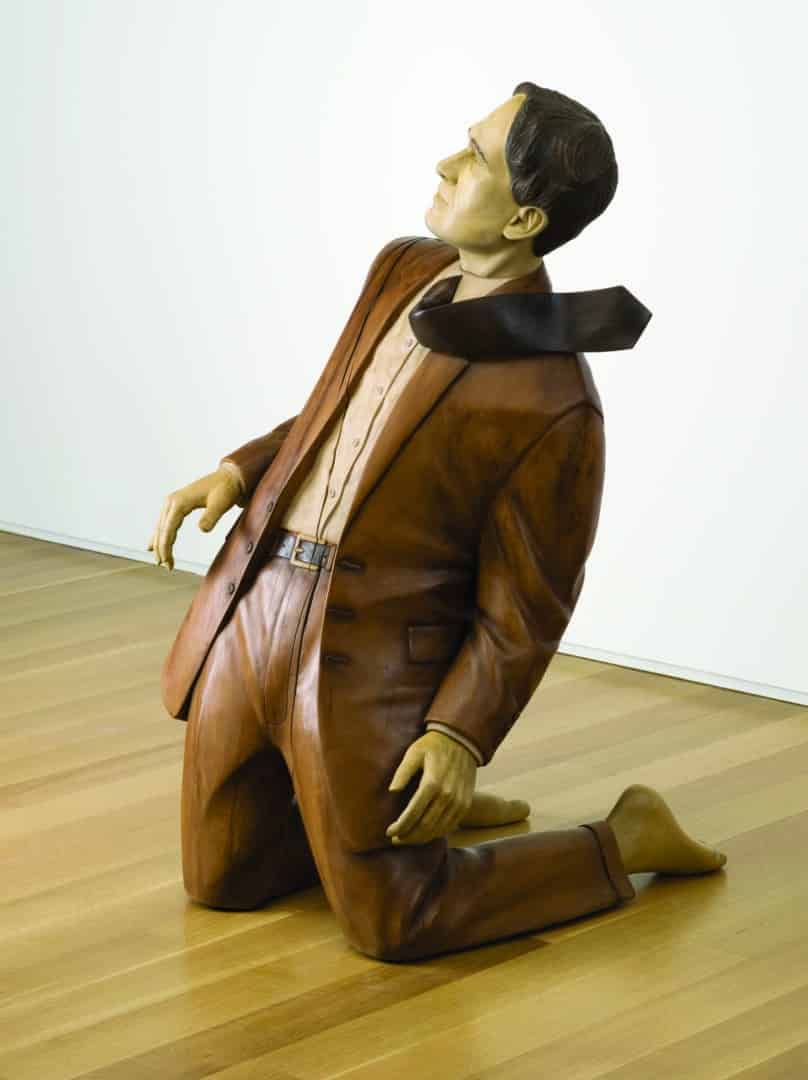

Then there’s the kneeling, brown-suited man called Martin, clearly witness to more than a few setbacks. His tie flies back over his shoulder as though he’s facing a stiff wind. Oddly, he’s barefoot. Looking apprehensively heavenward, he appears extremely vulnerable to the forces of nature. A quarter-inch split runs the length of his body.

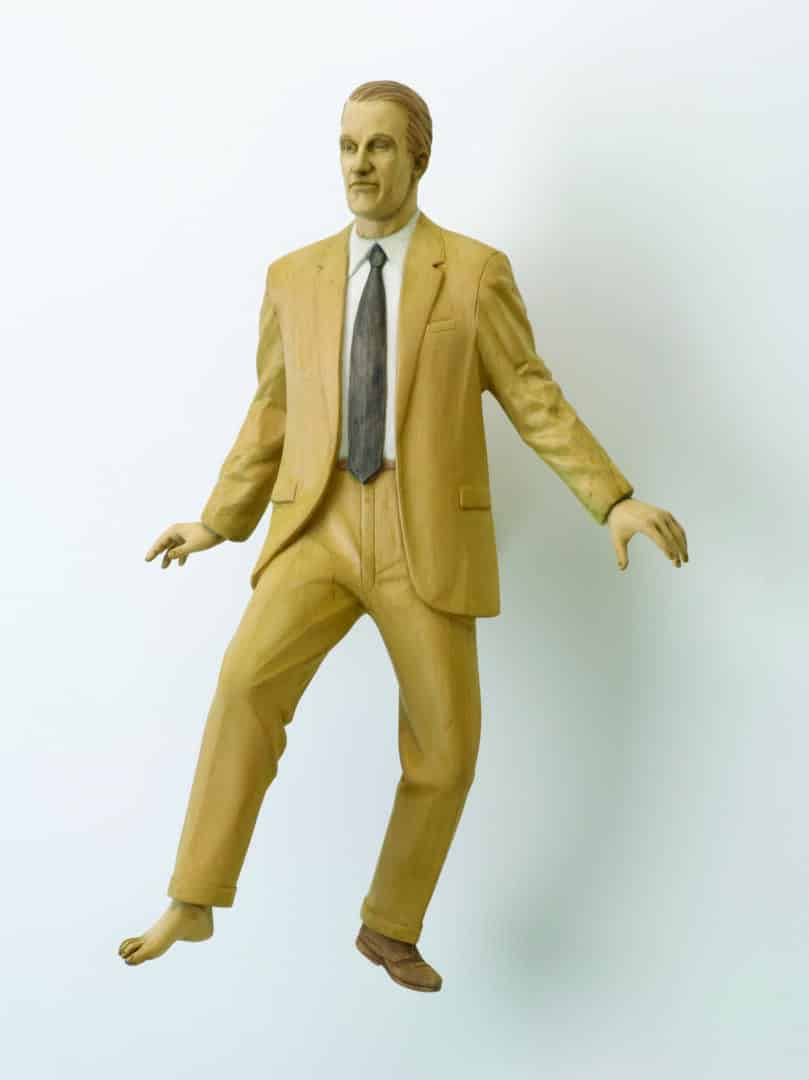

The sum of his parts does not add up. “The unseen stuff there is just as important as the seen,” Trotman said. “I want to provoke something, like Kafka and his axe, to smash up the frozen sea within us. It’s what Aristotle said – it’s art as catharsis.” And the well-dressed, khaki-suited man, with one shoe on and one off, cautiously slipping his toe forward? “He’s getting his foot wet,” Trotman said. “That one’s used to teach creative thinking. It’s about the existential anxiety of being in the moment.”

One gallery contains five larger-than-life, authoritarian busts, aligned against the wall as though on reverential display in the U.S. Senate or a Roman Hall in the Eternal City. Though they appear to be powerful and stoic individuals, it is the viewer who in fact possesses the real power to manipulate. Within each face is a removable element – a pair of eyes, a nose or a mouth – that can be taken out and reversed for a new and improved outlook.

Ironically, the former fine furniture-maker-turned-sculptor found early inspiration for this kind of work in wood from a late Gothic/early Renaissance sculpture. He experienced it first in one of the galleries of the NCMA’s East Wing in the early 1990s. “Female Saint” was carved by Tilman Riemenschneider centuries ago from linden, one of the woods that Trotman favors.

“This was the first of his I’d seen in the flesh – and there’s something psychologically connected between flesh and wood,” he said. “That wood was alive once. Linden trees grow big, and there’s not a lot of grain patterning. It’s like white marble – it’s a light wood, a blonde wood.”

The three-dimensional face of the saint excited him then, as it does today. He can move around it, almost in a dream state, and view it from all sides – even from the unfinished back that reveals its source. “There’s something about the fact that it’s a crude log in the back – but the front is so refined and graceful.”

Tellingly, it wasn’t a reverence for the saint that spoke to him, but how the artist plied his details. “It’s the delicacy in the way he’s handled the material – the way it bunches out in a space for itself. It’s very exciting for me.”

At heart, Trotman is an artisan with the highest regard for the standards of his craft. But he’s a philosopher too – and one with a message for the times in which we live.

“In a way, we’re all falling into the future, into the unknown,” he said. “The only way to deal with it is by plunging forward, and try to do the best we can with what’s coming at us.”