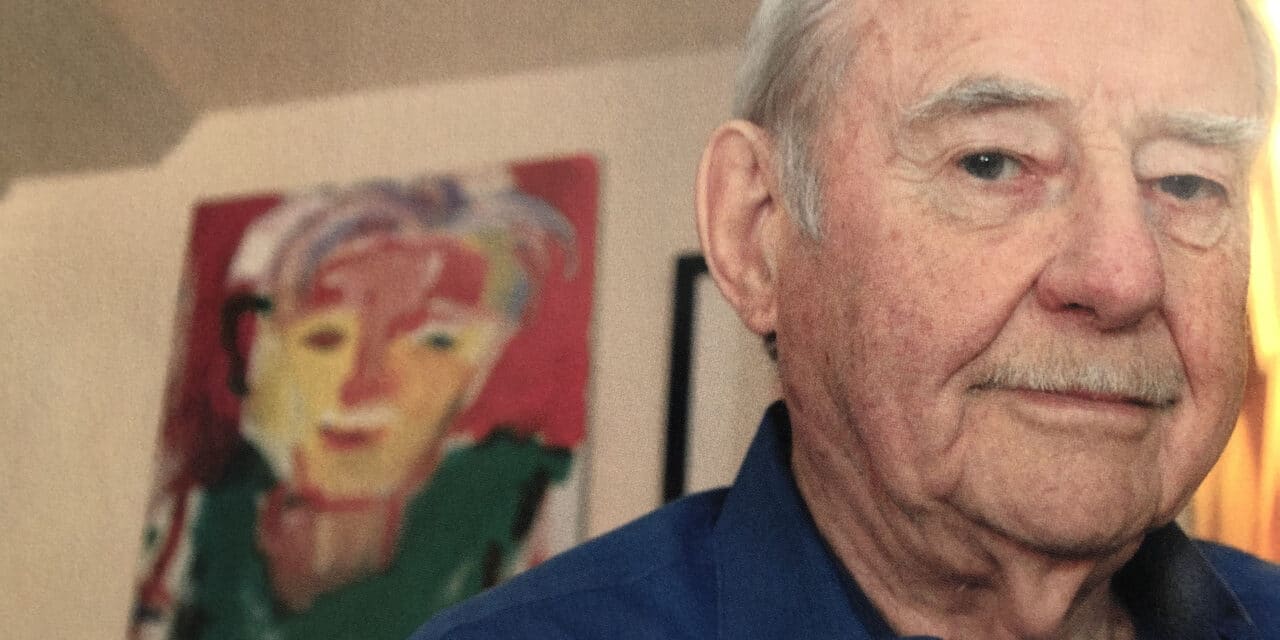

KARL KASTEN – A CHARMED LIFE

By ERIN clark

Karl Kasten started up the gangplank when he looked up and locked eyes. “There at the top was the most gorgeous creature I’d ever seen. She had this luscious red hair.” Karl knew she was trouble of the very best kind. He stayed away from her for most of the transatlantic voyage. After all, he was not looking for complications. It was 1957. The war was long over and Karl was busy building his art career. In fact, he was returning from a sabbatical in Paris when he had that first fateful encounter. The second would come on the final night of the journey. Karl broke down and asked the woman with the beautiful red hair to dance. “The seas were a little rough that night, so the boat was rocking back and forth. It kind of sent us sailing across the dance floor. We had to hold on tight.”The voyage was ending the next day, so Karl asked her to meet him at “The Met.” Much to his surprise, she showed up and, as he says, the rest is history. It was appropriate that their first official date was at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The two great loves of Karl Kasten’s life collided on that day: Georgette with the fiery red hair and an unrelenting passion for art in its many forms. Those two things would form the foundation for what Karl Kasten calls “a charmed life.”

Karl Kasten arrived on March 5, 1916, born to German immigrants living in San Francisco. His father was an electrical machinist. known for salvaging San Francisco’s fire alarm system. After the earthquake and fires of 1906, the city put together an elaborate fire warning system, but it didn’t work. Ferdinand Kasten figured out why. It was simple, really. When the engineers put the control board together, they used lead pencils to draw lines making sure they made the right connections. It turns out the lead short-circuited the whole system. Karl’s dad simply erased the lines and the system worked! To this day, Karl Kasten tells his students, “To be an artist all you really need is a pencil and an eraser. The eraser is important.” There is no question that Karl Kasten’s father had a profound impact on his son’s life, his thinking and ultimately his professional path. From early on, young Karl loved to draw. In fact, that’s what he did most of the time, and his father was supportive. When Miss Johnson, Karl’s sixth grade teacher, sent a note home complaining, “All Karl does in class is draw,” his father sent a note back saying, “Let him draw.” When Karl was 12, he was enrolled in Saturday classes at the California School of Fine Arts, and by the time he was a senior in high school, his teachers were pushing an art career. Karl had no doubts.After two successful years at Marin Junior College, Kasten enrolled as an art major at the University of California. Berkeley was (and is) a magical place for Kasten. It just fit. He worked his way through school by taking odd jobs, including some commercial work and cartooning. Karl graduated in 1938, the same year Cal won the Rose Bowl by beating Alabama. Kasten contributed many a cartoon to the school newspaper that year, chronicling Cal’s run for the roses, and he designed card stunts for the big game. Card stunts are a time honored college football tradition started at Cal in 1910 – students, in the stands, hold up cards and collectively send a message or form a picture. College football, especially big time successful college football, leaves an impression. Kasten remembers it as if it were yesterday. Football would again figure into Kasten’s life a few years later, but that’s a story for later. At this point, it was all good for Karl Kasten. After graduation, he enrolled in the Cal master’s program and became a teaching assistant to Worth Ryder. Ryder was part of the so-called “Berkeley School” – a group of painters in northern California that was bringing recognition to the west coast art scene. Ryder would become a lifelong mentor and friend. Kasten was well on his way to establishing a career of his own, but global politics were about to intervene. He actually won the prestigious Phelan Art Scholarship but couldn’t go to Europe because the world was the verge of war. So instead, after earning his master’s degree, Kasten took a job at the California School of Fine Arts. He wouldn’t be there long.December 7, 1941: the day that changed everything. The Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and Kasten was immediately drafted. It was a gut-wrenching time for the young artist. He was a pacifist. He thought about draft dodging, even before it was a part of the popular mindset, but in the end, he decided that his country needed him. Right or wrong, it was his country and he would fight for it.

High arches almost kept him out of officer candidate school but he somehow managed to talk his way in. He was a “shave tail,” a second lieutenant. “Do you know what a ‘shave tail’ means?” he says with a smile. “Mules that are tough, or in other words, stupid mules! That’s what I was.” During training there was a little time for fun, and the guys liked to play football. Kasten was a great receiver and there was one particular catch that stood out. He was racing down the sideline. The ball was slightly under thrown. Kasten had to turn and dive back. Everyone on the other team insisted the ball hit the ground, but standing just a few yards away was a battle-worn colonel. He looked at Kasten and said, “It was a good catch.” Little did Kasten know how that moment would affect his life. When D-Day approached, and that one tough hombre of a colonel was putting together his company, Kasten was on the list. He later asked the colonel why he would pick a misfit pacifist artist. Colonel Carter said it was the catch that impressed him. Turns out, the colonel made a lasting impression on Karl, as well. “He was the type of guy that wouldn’t let his men disarm a landmine. He would do it himself. He was a role model. He showed me how to take care of details and, more importantly, how to take care of the people you’re responsible for.”Kasten was promoted to captain just before the 295th Engineer Combat Battalion hit Omaha Beach on D-Day. For the next two years, Kasten was a soldier. He didn’t like any part of it and says he was on autopilot most of the time. Shaking his head as if he still can’t believe it, he states, “My job was to kill people.” Even now, more than 60 years later, he gets teary-eyed talking about it. He remains a pacifist and steadfast in his belief that violence is never the answer. “War never solves a damn thing.”When the war was over and Kasten returned stateside, he threw himself into his art and his career. The University of Michigan offered him a teaching job and he took it, he says, “mainly because they were the only ones asking,” he says. That wasn’t entirely true. Worth Ryder, his mentor back at Berkeley, was trying to recruit Karl to come back, but Karl felt he had to leave and get established elsewhere before returning. So he headed off to Ann Arbor and the University of Michigan. Kasten spent two years there before the brutal winters sent him heading home where he joined the faculty of San Francisco State University. Kasten spent the next couple of years experimenting and learning, and, truth be told, taking advantage of the GI bill – the government’s promise to pay for a veteran’s

education.

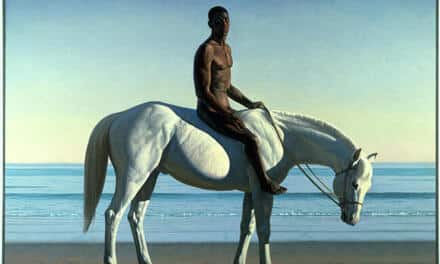

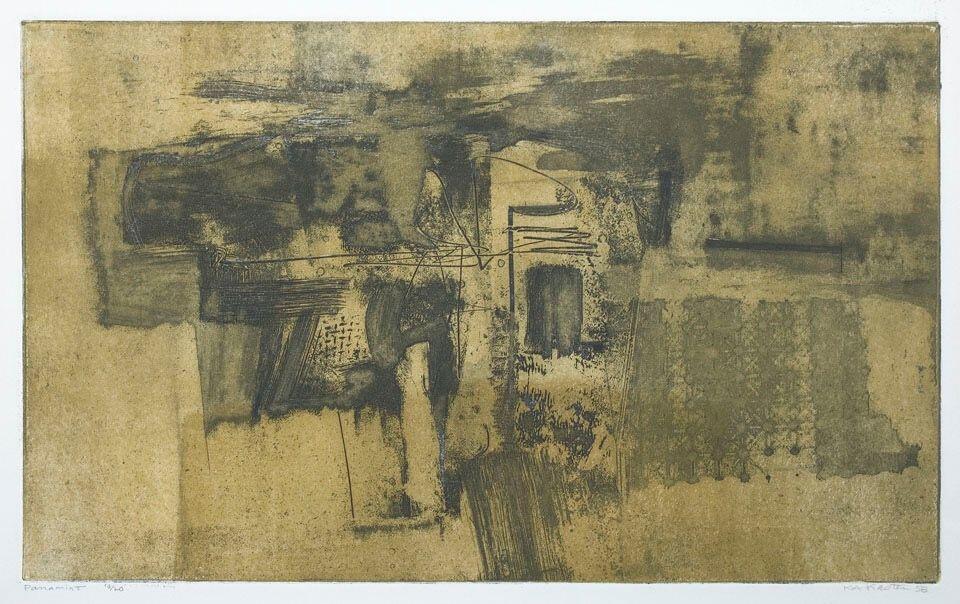

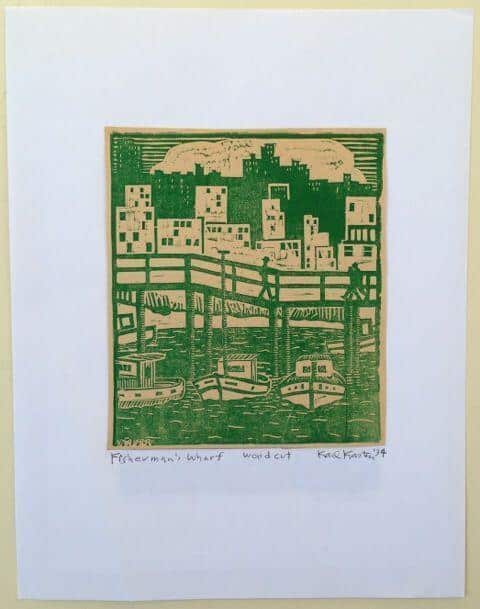

Through the years, there have been many great artists and many great teachers but they are not often the same people. Kasten is one of the exceptions. Maybe because all of his role models – mainly Worth Ryder and the great Hans Hofmann – were exceptions too. Art critics often mention Hofmann in the same breath as Pollock and de Kooning. In fact, the rap on Hofmann is he spent too much time teaching and not enough time on his own stuff. He was the first to do drip paintings, but it was Jackson Pollack who perfected the technique and was ultimately given credit for it. Looking back on his own career, Kasten is well aware that he may someday get the same rap – too much time teaching, not enough time on developing his own distinct style. But in 1952, he wasn’t thinking about that. Looking to keep painting and take advantage of the GI bill, Kasten went to Cape Cod to study with Hans Hofmann.He spent the summer in Provincetown painting, learning, and developing his own theories. Perhaps his most provocative idea, and the one he believes will be the foundation of his legacy, has to do with space. “Space is unique to painting. A blank canvas represents infinity and space, but it’s also flat. You’ve got this crazy phenomenon going on. It’s paradoxical. As soon as you put a line on that canvas – boom! – you open up space all around the line. The canvas is kind of a living thing. In the case of Hofmann, he was a great proponent of push-pull. His idea was that you put color here and another color there – maybe red here and blue here and you make the blue come down and the red come up and another color here, and before you know it the whole surface is pulsating because of the color that advances and then recedes. Of course, it’s more complicated than that, it also depends on the lines you use – thick or jagged. Gauguin discovered line as a thing other than contour. The line was as important as color or texture. It’s in the bag of tricks an artist can use.” Kasten gets excited and animated as he talks art theory, and it’s clear he is a student of history. He has studied the masters, especially Gauguin and Cezanne, and isn’t shy about “borrowing” their ideas. He figures that “if it’s out there, you might as well grab it.” From the greats of the past to his contemporaries, many have influenced Kasten but no one had greater impact on his life or art than Worth Ryder. “His use of texture and abstract lines were a great influence,” says Kasten. And it was Ryder’s persistence that would set Kasten on his life path as well. Two years into his stint at San Francisco State, Ryder called – again – and offered Kasten a position at Berkeley. Kasten knew it was the last time it would be offered, and it was an offer he couldn’t refuse. He had come full circle: back at his alma mater and ready for the next chapter.Although Kasten has always considered himself a painter at heart, he is perhaps best known for his pioneering work in printmaking. He learned from the best, spending a summer studying with Mauricio Lasansky at the University of Iowa. Lasansky had learned technique from the legendary Stanley William Hayter. Kasten says, “Hayter revolutionized printmaking. Up until Hayter, printmaking was considered a craft. The artist really wasn’t involved in the printing process and for that reason, many artists looked down on print makers. Hayter changed that.” In simple terms, Hayter got his hands dirty. Instead of making a drawing and transferring it the metal plate for printing, he developed the print as he went along, altering plates along the way. The metal plates were his canvas. It sounds so simple now but it was revolutionary back then. He was the first to use the process to develop the art instead of the other way around. Lasansky took that a step further by cutting or etching deeper into the print plate, giving his prints more complexity. Kasten learned Lasansky’s “intaglio technique” and took it back to California where he set up printmaking departments at both San Francisco State and Berkeley. Kasten took the ball and ran with it. He pushed printmaking to new limits, experimenting with collagraphy and lithography, and always looking for ways to improve the process. In fact, several decades later he invented a printing press that greatly increased the vertical force so he didn’t have to use as much elbow grease to make his print. The K-B etching press went into production in 1980 and one of the originals still sits in Kasten’s studio today.

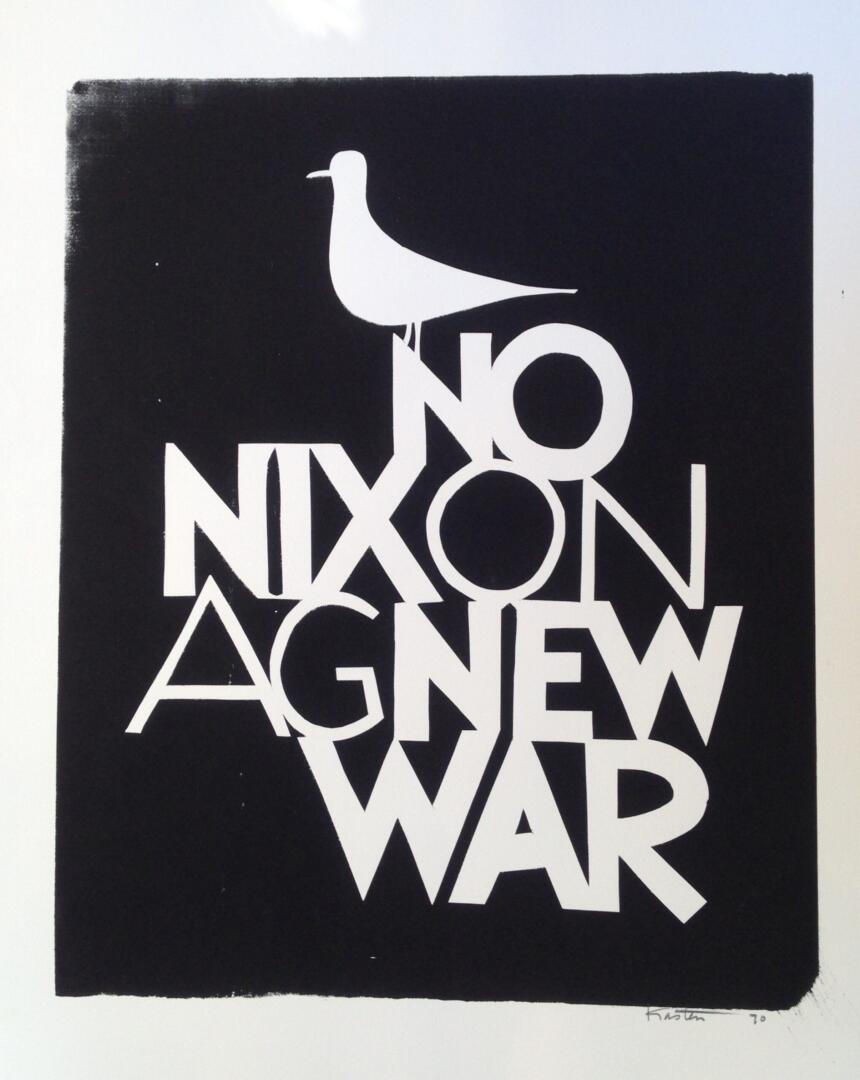

The decade after the war was an unsettled time for Karl Kasten. He admits he “rambled” around a bit, looking for focus. A quick trip through his resume proves the point: University of Michigan, University of Iowa, Hofmann summer school in Provincetown, and San Francisco State before finally landing in Berkeley. A sabbatical to Europe in 1957 capped off a frenzied 10 years for Kasten. He met Hayter at his famous Atelier 17 studio in Paris and on his voyage back he had that fateful encounter with a gorgeous, French-born redhead. He and Georgette Gautrier were married a year later. It would be Kasten’s third trip down the isle, but this time it stuck. The newlyweds settled in the Bay Area and started a family.After traveling the country and the world, Kasten was ready to build his own thing. He and his cohorts – many call them the second wave of the Berkeley School – were quietly putting the west coast on the artistic map. “In the late-fifties, (Willem) de Kooning came on the scene and everyone followed him,” Kasten laughs. “He got me into abstract expressionism – AE. The thing about AE and printmaking is you don’t always know where you’ll end up. If you’re lucky, nice things happen.” For Kasten, nice things did happen. “Kasten is a great student of history,” says David Carlson, an expert on the Berkeley School. “He studied with great painters, like Hofmann, and he studied painters of the past, incorporating what he learned into his own work. At first glance his abstract expressionism paintings are dark, but look closer and you see the color coming up from underneath. Kasten was part of the second wave – heavily influenced by Hofmann” (see inset).Ironically, as Kasten was finding his own personal compass, the world around him was exploding. It was the sixties and Berkeley was pretty close to the epicenter of the counterculture. Given his views on war, you might expect Kasten to be in the middle of the protests, but actually the angry crowds turned him off. “It seemed as if all hell broke loose on campus. And I just didn’t like the mob scene.” He contributed a few biting political cartoons, but for the most part he didn’t join in. “I’ve just always thought violence was dumb.” Art was his outlet, and that’s where Karl Kasten put his energy.As the sixties came to a close, Kasten’s art changed rather dramatically. Hard edge acrylics, very precise and geometric, replaced the freewheeling abstract expressionist paintings. “I suddenly decided AE was too easy and I wanted to do more calculated work. AE was so pleasant to do. I wanted to agonize more. When I started the geometric print-like paintings, I really thought I was onto something. These classical paintings were never really a commercial success.” But he didn’t care. As a tenured professor of fine art at one of the best universities in the country, Kasten had the freedom to experiment and sometimes fail. And Kasten took full advantage, trying many different things over the years. He admits he may have moved “too easily between styles and periods. Maybe I could have been a big wheel in my field if I had just stuck to one thing.” In reality, he’s doing just fine. Kasten will go down as an artistic innovator – in printmaking and in painting. And he was a great teacher.

Throughout his 33 years at Berkeley, Kasten was involved in and out of the classroom – he did stints as assistant dean and vice-chairman of the art department. “It took time away from my art, but I felt it was my responsibility. A lot of artists wouldn’t do it, but you know, I kind of enjoyed it.” Kasten was happiest, though, when he was teaching. His favorite class was a popular materials and techniques course, which he founded. Students not only learned about egg tempera, watercolor, gouache, oil glazing and graphics, they also got a chance to experiment with all those materials. For art students, it was akin to kids playing in the mud. Great fun, but Kasten also expected a lot of from his students. He was known to be brutally honest, but just as quick to praise good work, even if it wasn’t exactly what he was expecting. He tells the story of one student in his mural class. For the final exam students were given a section of wall in the art building and told to go at it. “This one guy had paint all over the place. It was a real mess. He had thrown paint everywhere. Very defiant,” Kasten says. But something happened as he studied the piece. “It wasn’t the traditional way to paint a mural, but he made it work. I realized that it was very deliberate. It was fantastic. I gave him an “A” and, guess what? That student now teaches at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.” Kasten’s eyes twinkle when he tells the story. He’s always liked the unpredictable.

Today at 90-years young, Kasten still lives in Berkeley with his wife Georgette. The five kids are grown and gone, but the house is still full of life. It seems every square inch of wall space is covered with something. A lot of it is Karl’s work – an abstract expressionism piece on one wall – a geometric acrylic above the fireplace, but there is also Cezanne, Gauguin, de Kooning, and even a small David Hockney tucked away in the hallway. Karl explains, “Oh, yeah, David was at Berkeley for a summer session. He walked into my office and I made him draw me a little something.” That little something, on a scrap piece of paper, is now framed and on the wall with the many other stories that make up his life. Karl’s studio is in the attic – a sunny place with a beautiful view of Berkeley and beyond. You have to climb a perilous ladder to get up there. but it kind of adds to the charm. As he sits in this space contemplating his life, Karl Kasten looks comfortable and content. Berkeley is still a big part of his life as well. He walks the campus at a pace that would put many younger men to shame. He has been retired for more than 20 years, but it’s clear this is still his place. The faculty club, where he still goes to lunch frequently, is much more casual than you might expect; serve yourself and find a spot. It’s not unusual to hear snippets of animated conversations -about physics, literature, art, and sports. Karl loves it. He seems to soak it all in. Kasten is educated far beyond the world of art. He can talk engineering, the teachings of Nietzsche or even physics but his basic philosophy is quite simple – the four H’s, as he calls them. The four things you need to be successful in art and life:1. Hands – You need to control your hands (life and art).

2. Heart – You are nothing without passion.

3. Head – Passion is great but you need to use your noggin, too.

4. Heaven – You have to rely a little bit on “the guy upstairs.”Kasten says he’s lived by those four simple H’s and they’ve served him pretty well. There have been some ups and downs but overall he says he really has lived a charmed life.